OCTOBER 20, 2020 – Yesterday I launched my annual “bud-cap” operation in the tree garden. The work protects pine sapling leaders from foraging deer once the snow flies. The bud-caps are 4 x 6 paper folded over the leader and stapled in place. Conditions were perfect, and I bud-capped 292 trees. The operation continues today—before snow arrives.

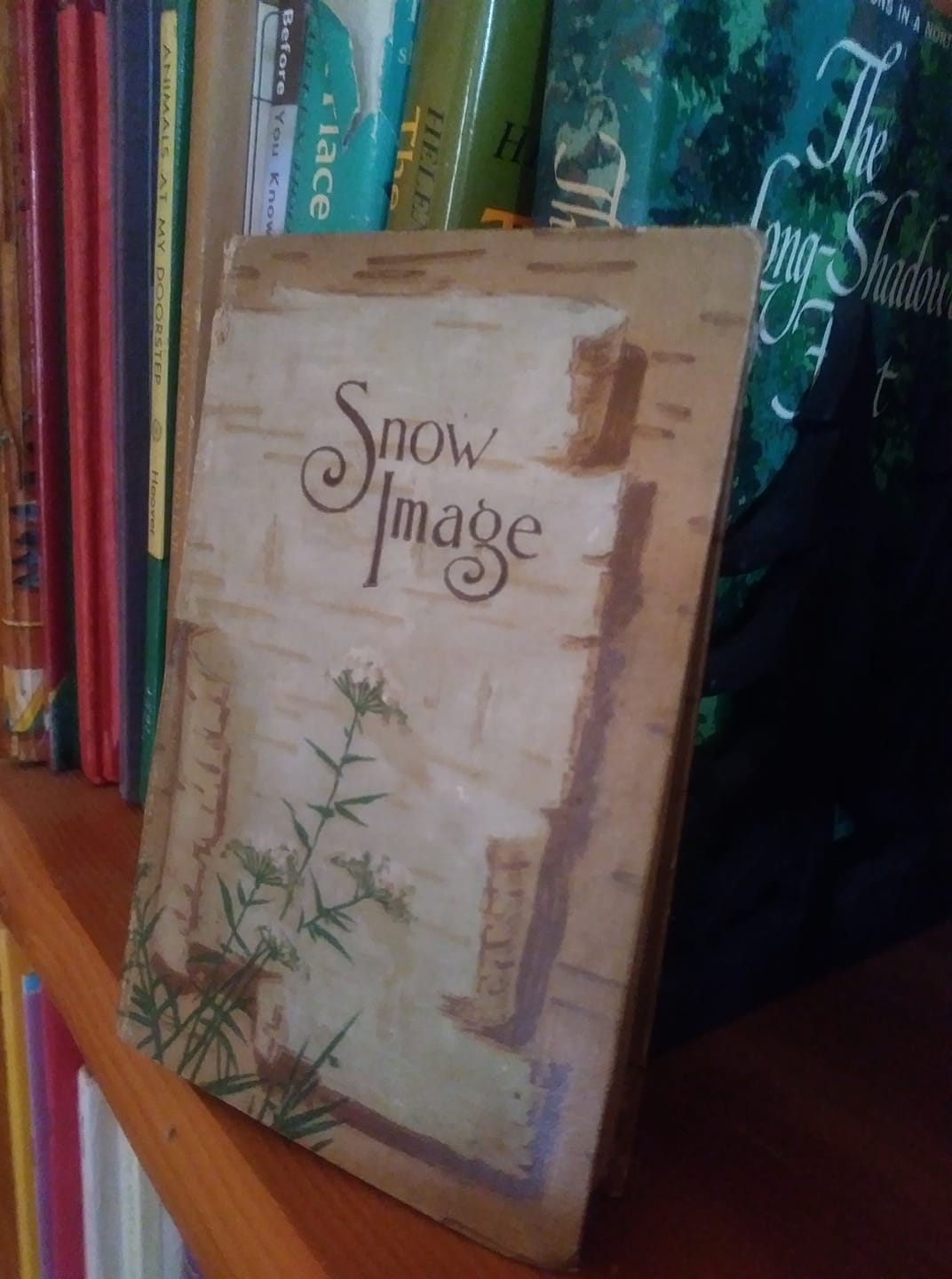

During a break, I repaired to the cabin to warm my hands. While rounding the bookcases at the head of the log stairs to the loft, I noticed resting on a shelf, front cover facing outward, an old but well-preserved little book called, Snow Image. The cover design imitated birch bark so realistically, I thought initially it was actual bark. I lifted the book from the shelf and opened the cover. It’d been a gift to my wife’s beloved great aunt, Alma—someone I’d never met but have come to know by my wife’s fond stories about her.

I turned to the title page: The Snow Image and Other Twice Told Tales by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Originally published in various periodicals, the stories were later published in book form (hence “twice told”) in two volumes, the first in 1837; the second, 1842. The edition in hand had been published in 1899.

I turned to the Preface—a letter written by Hawthorne in 1851 to his close college friend, Horatio Bridge. The college, I knew, was also my alma mater. (Freshman year I lived in the same dorm that Hawthorne had occupied, 1821 to 1825.) In the letter Hawthorne alluded to the halcyon days that he and Bridge had experienced at the “country college,” which fired memories of my own idyllic time there.

The Introduction was by one Richard Burton—a professor of English literature at the University of Minnesota—who explained that Bridge had been instrumental in giving Hawthorne vital encouragement when the author was depressed about his life as a writer.

In the moment I was struck by the connections surrounding that little book—the birch bark cover, reflective of the rustic surroundings outside the dwelling where I’d discovered the gem; the book’s original ownership by my wife’s beloved relative; my shared affinity for Hawthorne’s alma mater; the introduction writer’s place of scholarship—my home state; and however fleeting, the collection’s lead story title—Snow Image—harbinger of the morrow’s weather.

I took the book downstairs for later reading—much as I’d put aside for deferred gratification, a sampler box of fine chocolates. I then headed back into the tree garden to resume my bud-cap operation.

An hour later my wife called. She’d returned to the cities the day before. I told her about my discovery, and she said she’d found the book while looking over the shelves during the weekend and had left it sitting there.

After the sun had reclined and my day’s work was done, I relaxed in the warmth radiating from the wood-burning stove. I opened the little “box of chocolates” and savored the first story. Harsh realities of the world soon melted away.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2020 by Eric Nilsson