JUNE 11, 2021 – Years ago while browsing the shelves of an independent bookstore, I encountered a tome called, Empire of the Czars by Marquis de Custine, a French nobleman who spent three months in Russia in 1839. His acerbic insights endured as a companion to the discerning examination of the United States by his contemporary countryman, Alexis de Tocqueville. As a self-styled student of Russian history, I bought the book, read it, and shelved it . . . until now.

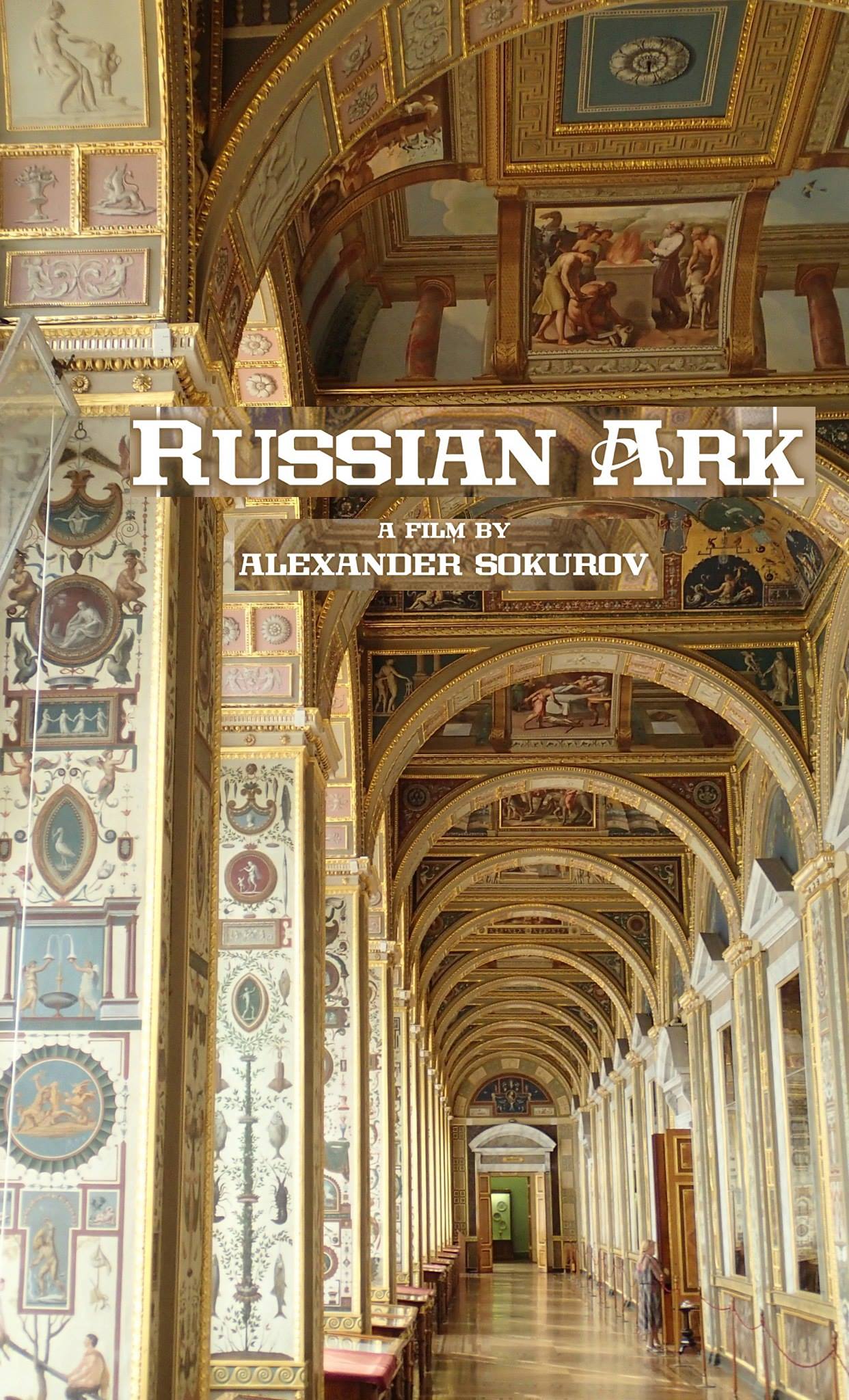

Last weekend, a high school friend (Christian – see 6/08 post) of our younger son, recommended a film called Russian Ark. I’d never heard of it. It turns out to be one of the most unusual movies ever made—93 minutes of continuous filming inside the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. It’s such an extraordinary production, I watched it twice. Who should the principal character be (among a cast of thousands, including Peter the Great and Catherine the Great), but the Marquis de Custine himself!

In life, Custine was a colorful personality, to say the least, but a tragic one as well (his grandfather, a revolutionary, was later guillotined, as was the young boy’s father; his mother was imprisoned and stripped of her wealth, but possessing Amazonian strength of character, she staged a stunning recovery).

In the movie, the Marquis—identified only as, “the European”—is portrayed as a highly refined and thoroughly amusing kook, who leads us and the narrator through salons of the Hermitage and through time, from Peter to the present.

Custine the writer and Custine the film character both are right about Russia being a European “pretender.” In the latter role, he initially spares the place no relief from contempt. “Russian music gives me the hives,” he says to the narrator, who, by the way, is a Russian who divulges that he died in some accident and is now a specter—like Custine—wandering through the Hermitage. But as the film unfolds, Russia’s elegance grows on Custine. He joins the dance floor in a nine-minute segment featuring a grand ball of Russian princes, princesses, and young officers, all decorated in full, pre-revolutionary plumage, twirling and gliding gracefully to the music of Glinka, performed by an orchestra that at the end is cheered as if by fans at a modern football game.

If you’re an arthouse film fan, this production is a bonanza—even more so if you love the works of Van Dyk and Reubens (for example) and how deeply Russians do too or are a connoisseur of Glinka—performed by Russians, giving you not hives but goosebumps—or are a student of Russian history or followers of art historians Orbeli or father and son, Boris and Mikhail Piotrovsky (directors of the Hermitage Museum—Stalinist period, forward). If you possess any of the foregoing afflictions, you’ll find immense pleasure in this quirky film. It’s simply like no other you’ll ever see.

A country that can produce such a work is deserving of our admiration, however much we might condemn the Russian underside.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2021 by Eric Nilsson