MARCH 12, 2025 – (Cont.) I was never the literary cognoscente that my sisters and bros-in-law Chuck and GK are or that my late bro-in-law Dean and my parents were. To the extent heretofore I’ve read literature generally or Russian literature specifically, I’ve never explored the background of any writer—just as I never concerned myself with biographical information about great composers or musicians. In the case of lit or music, I was focused solely with the words on the page or the notes in the air. (Why, I want to know, did my various instructors not open the doors and windows into context and background to what shaped the perspectives of the writers and composers whose works I was trying to understand?)

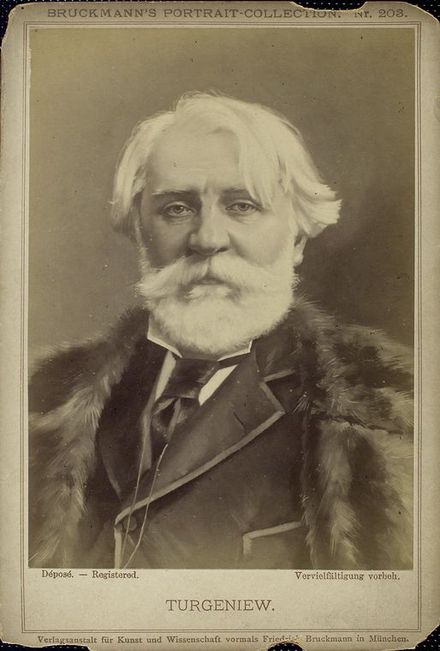

When it came to the literature of Gogol, Pushkin, Tolstoy, Lermontov, Dostoyevsky, Chekov—and Turgenev—I was clueless and shockingly incurious about the details of their lives and eras, which details are critical to understanding the views and conditions reflected in their works.

In the case of 19th century Russian literature, the essential frame of reference is the social environment, shaped as it was by the individual stamp of each successive Tsarist regime from Alexander I to Alexander III (with Nicholas I between Alexanders I and II).

Turgenev was a kid during the last seven years of the reign of Alexander I, a well-educated monarch with reformist inclinations at the start of his 24-year rule. Initially he surrounded himself with liberal (against the standards of the time) advisors. A leading idea supported by the young Tsar—just 23 at the time he ascended to the throne upon the murder of his mean, nasty father Paul—was establishment of a constitutional monarchy, if one can fathom that. He initiated a rational approach to the organization of ministries, establishment of universities, support of the arts and scientific inquiry. Most notably, he wanted to resolve the “serf problem,” a huge anchor dragging down the hope of progress in a country largely mired in fossilized mud. Thomas Jefferson considered him an instrument of good who would imbue the Russian masses with “a sense of their natural rights.” Beethoven, who’d become disillusioned with Napoleon, Alexander’s nemesis after the Corsican abandoned Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité, dedicated his Violin Sonata No. 6 to Alexander (Napoleon’s later nemesis!), who, in turn, presented Ludwig with a big diamond[1] when the Titan and the Russian monarch met in Vienna.

Even before the end of his reign, Alexander had shifted from his liberal ideals. On the day Alexander’s brother and successor was to take his oath as Emperor, 3,000 young army officers, joined by liberals seeking more representative government staged a demonstration in Senate Square a little over 2 km from the Winter Palace. Nicholas ordered loyal troops to put down the rebellion. Blood flowed, and the whole scene went down as the “December Revolt.” It initiated a period of severe repression, executed by what was called the Third Section—a kind of precursor to the NVDK and KGB under Soviet rule. Writers, artists, and intellectuals were targeted for prosecution, imprisonment, and exile. Ironically, however, the Golden Age of Russian Literature (1820 – 1880) overlapped with this oppressive environment. As would occur a century later, many would leave the country—including the celebrated socialist-writer-thinker Alexander Herzen and our friend Ivan Turgenev, both of whom would wind up settling in Western Europe.

Turgenev lived in France and proceeded to write his first novel, Rudin (1856), depicting the frustrations of a young man’s idealism under the rule of Nicholas I; Home of the Gentry (1859), Turgenev’s most popular novel—in its day; On the Eve (1860), a social comedy; and (drum roll . . .) Fathers and Sons (1862).

I have yet to read this novel, understand, but I’m familiar with its basic tension—the old order vs. the new; conservative fathers vs. revolutionary sons. One commentary describes the protagonist Barazov, a nihilist, as the “original Bolshevik.” The book’s six-year setting was a consequential period in Russian history, encompassing both the Crimean War and the Emancipation of serfs. Adverse reader reactions to the novel led Turgenev to leave Russia, which was not a popular move on his part. Discouraged by criticism of what would become his best known work among future generations, he lost his momentum as a writer. In 1867 he published Smoke, in which he criticized Russian society. A decade later he published his final novel, Virgin Soil, in which he served up further criticism of his native land.

What Turgenev’s author-peers thought of him is intriguing. Henry James and Joseph Conrad both preferred his writing far ahead of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky; Nabakov, on the other hand, in his Lectures on Russian Literature, said “Turgenev, is not a great writer, though a pleasant one,” but nevertheless ranked him fourth behind Tolstoy, Gogol, and Chekov, but superior to Dostoyevsky. Go figure.

And then there was Isaiah Berlin (1909 – 1997)—the extraordinary Riga-born Jewish-Russian-British Oxfordian scholar of political theory, philosophy, and intellectual history, whose family survived the Russian Revolution, then fled to Britain. Berlin applauded Turgenev’s commitment to Russian liberalism and the writer’s effort to free the Russian mind. In a lecture on Fathers and Sons, Berlin identified the problem—and Turgenev’s solution:

He knew that the Russian reader wanted to be told what to believe and how to live, expected to be provided with clearly contrasted values, clearly distinguishable heroes and villains [. . .] Turgenev remained cautious and skeptical; the reader is left in suspense, in a state of doubt: problems are raised, and for the most part left unanswered.

In any event, I’ve begun reading Turgenev’s classic and am savoring every detail. I know it’s a little late in my reading career to be experimenting with a new approach, but why not? I’ve decided to s-l-o-w . . . w-a-a-a-y . . . down to a rate that guarantees apprehension, comprehension, and retention. Professor Stavrou’s reading list requires a quicker pace elsewhere, but when it comes to Russian literature, the reader can’t be rushin’ it.

Stay tuned.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Not to put too fine a point on the multi-faceted gem, but Alexander’s gift to the great composer reminds me of the Russian infatuation with “big.” When I crisscrossed the country in 1981, I was amused by Russian pride in their oversized wristwatches. After observing this twice when I asked people for “the time,” I made sport of it. Aboard the train, I’d randomly ask people (by gesture), “What time is it?” Invariably, they’d proudly pull up a sleeve to reveal a gigantic digital watch. In the West, the size of such long-familiar devices had already shifted in the opposite direction—smaller was better . . . and more fashionable. Not in Russia. The relatively new “technology” was best displayed in large dimensions. This notion of “big is better” seemed to apply to many other things in Russia—actual “things” as well as the intangible ones (e.g. empire; distance; stature of everything Russian—particularly the place of literature on the international scale).