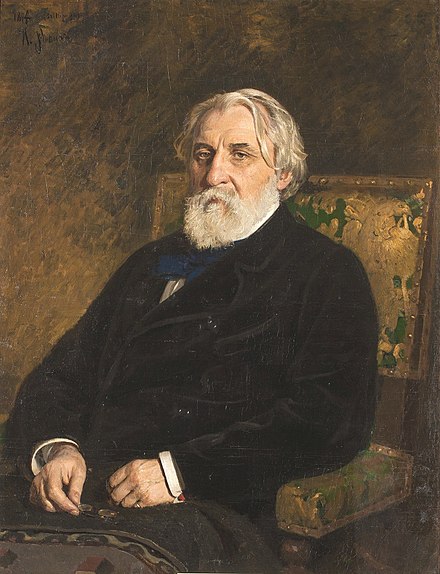

MARCH 11, 2025 – Though I might fashion myself as the “modern man,” just as the delusionary graduate of a six-week Berlitz language course might think of himself as “bi-lingual,” my comfort zone is the antithesis of “current.” For example, when it came to my turn for our book club’s next reading choice, I put forth Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev—born November 9, 1818 (two days before Armistice Day a century later) in Oryol, Russia, 230 miles southwest of Moscow and died September 3, 1883 in Bougeval, France (just outside of Paris).

I selected Turgenev’s most famous novel largely because our good professor placed it on the required reading list for the undergraduate Russian history course I’m currently auditing at the University of Minnesota. Call it a “kill two birds with one stone,” if you will, but an added advantage to my book choice is that given all the other heavy duty reading on my plate, Fathers and Sons weigh(s) in at only 269 pages—a piece of cake, a cup of tea, a stroll in the orangerie of some grand estate in the Russia of 1862, when the book was published.

Before diving into this classic, however, I decided to study the author’s background—an adaptation of Professor Stavrou’s eminent wisdom about reading history: “First, know the historian.”

Physically (at 6’4”) and figuratively, Turgenev was among the giants of the golden age of Russian literature. His father, Sergei, oxymoronically an impoverished nobleman, had been a cavalry colonel in the fight against Napoleon’s Grand Armée in 1812. Turgenev’s mother, Varvara, was from a wealthy but unhappy Russian noble family: her stepfather was such an ogre, she took refuge with her uncle after her mother died way too young. At age 26 Varvara inherited her uncle’s considerable fortune and three years later, married Sergei. They had three sons, Sergei, Nickolai, and our author-friend, Ivan.

The three were given top-flight educations, led initially by French, English, and German governesses. French, however, was the lingua franca of the household. Ivan attended university in Moscow, St. Petersburg and later Berlin.

As a kid, Turgenev was influenced by a family serf who read aloud verses from the Rossiad by the famous 18th century poet, Mikhail Keraskov. When Ivan himself took to writing, he was soon recognized as a literary talent.

His first big hit was A Sportsman’s Sketches, a series of short stories published in 1852. It won praise from the leading light of the pantheon of Russian writers: Tolstoy himself[1]. Based on Turgenev’s hunting experiences and observation of serf life on his mother’s sprawling estate (she controlled 500 serfs and lorded over them with as much iron discipline as she had over her three sons), the collection is said to have swayed many among the reading public to support the abolition of serfdom.

Unlike Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, Turgenev had little time for religion. By the standards of the time, he was a “lib,” attributable in large part to his education and travels in Western Europe, his pursuit of Hegelian philosophy, and his immersion in the classics and embrace of literature.

What jolts the modern reader is Turgenev’s derogation of Jews in an early story, The Jew (1847). Whenever I encounter such a grating fact about any admired artist, writer, musician, or statesman of the past, I wish naively that the cringe-worthy hadn’t been true; for example, I wish that none of the signers of the Declaration of Independence had been a slaveholder. But somehow we must reach personal reconciliation with the untoward reality or we run the risk of erasing foundational achievements from the record of civilization. In the case of Turgenev—and no doubt many other notable writers et alia of his era, given the ubiquity of antisemitism in places such as 19th century Russia (let alone the rest of Europe)—I have to understand historical context, not to excuse but to explain.

In any event, Turgenev broke into the literary scene late in the 30-year repressive reign of Russian Emperor Nicholas I, younger brother and immediate successor of Emperor Alexander I (r. 1801 – 1825). The writer would find himself in trouble, not for being a rabble-rouser or “campus radical”—he had a noble pedigree, after all—but simply for writing an obituary for Nikolai Gogol. The offending passage:

Gogol is dead! What Russian heart is not shaken by those three words? He is gone, that man whom we now have the right (the bitter right, given to us by death) to call great.

Inexplicably from our perspective, the censor for St. Petersburg banned this from publication. The Moscow censor was more lenient and allowed a newspaper to print it. For this act of liberality, the latter censor was fired, and our friend Turgenev was thrown in the slammer for a month, then exiled to his mother’s estate for two years. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] The admiration wouldn’t last. The two writers had a falling out, and at one stage, Tolstoy challenged Turgenev to a duel, though this step toward war was averted by peace, when having a change of heart, Tolstoy apologized.