OCTOBER 22, 2024 – Yesterday evening I experienced local government at ground level. My overall reaction to the encounter was, “Where was Norman Rockwell?”

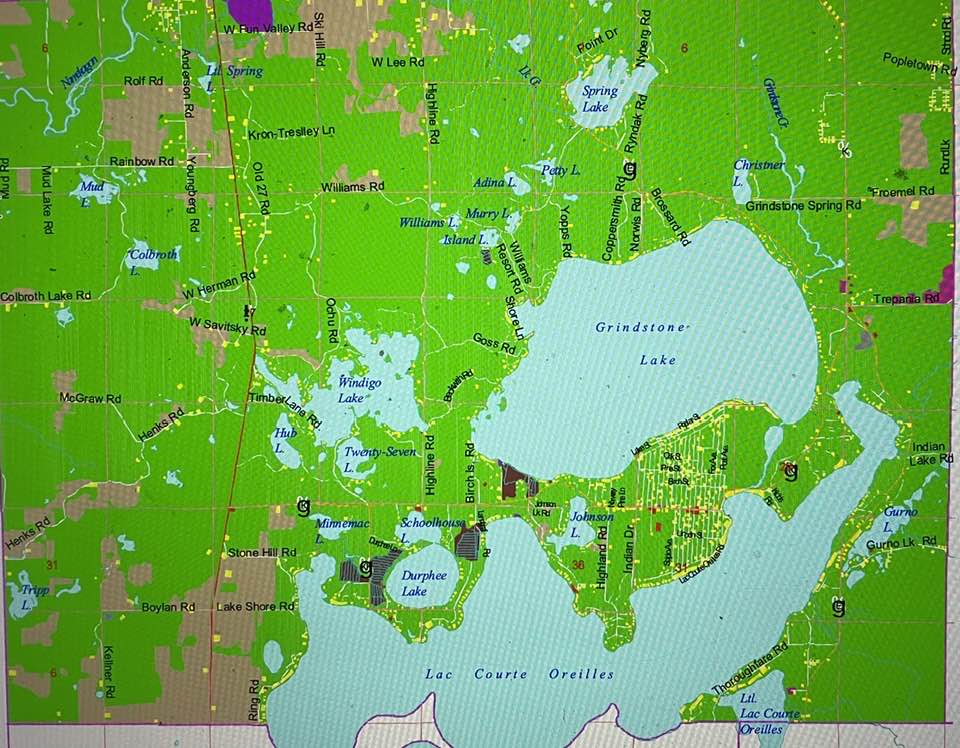

The place was the Bass Lake Township Town Hall between Grindstone Lake and Lac Courte Oreilles in western Sawyer County, Wisconsin. As far as anyone knows, there is no “Bass Lake” within the township borders, though if you wander within boundaries, you’re never far from a “no name” lake or pond; maybe one of them is full of smallmouth bass.

The occasion was the public hearing of taxpayer appeals of the recent reassessment of all real estate in the township. Last week I’d filed an objection to the reassessment of the main tract of Björnholm, which the assessor had increased by 242%. My appointed hearing time was 7:00 Monday evening, but in keeping with my compulsive professional punctuality, as opposed to my habitual personal tardiness, I appeared half an hour early.

The small unlit parking lot was vacant except for five vehicles, at least one of which in the dim remains of dusk appeared to be a late model F-150. Since the Board of Review consisted of three members of the town board, that left two out of the five—one belonging to the town clerk and the other for the assessor, both of whom, I knew, would be in attendance. This simple math meant I wouldn’t have much company among other taxpayers. Though my entrance into the compact space of the meeting area was conspicuous, none of the five officials gave the slightest hint they’d noticed me.

They sat at three long folding tables arranged in a U-shape and loaded with sheaths of papers. Two of the board members and the assessor wore baseball caps, so I saw no need to remove my own. One side of the room had been decorated with two sparkling vertical banners framing what at first appeared to be a way early Christmas tree but festooned with the symbols of American pride—flags, stars, ribbons, and bunting—and lots of shining gold and silver streamers. “The Land of the Free,” proclaimed the glittering banner on the left side of the tree, “Because it’s the Home of the Brave,” read its shining companion on the right side. I surmised that the people running the show in Bass Lake Township probably weren’t a bunch of lefties.

I’d walked in on the middle of the assessor’s detailed comparison of two properties, one of which, apparently, was the subject of contention between the assessor and an objecting property owner who, I surmised, had appeared earlier in the proceedings. Once the assessor had concluded his disquisition, the board chair intimated that they could now move on to other matters. If I wanted my day . . . er, evening . . . in court . . . er, township hall—I needed to step up and speak out now.

In fact, in an hour-long telephone conversation with the assessor over two weeks before, I’d voiced my objection to his reassessment of Björnholm. My factual basis was a recent appraisal I’d commissioned from a local appraiser whom the assessor knew and respected. After several thorough discussions with me by phone, the assessor ultimately accepted my arguments and lowered his number to match the appraiser’s. During these calls, we developed considerable mutual respect. In the end, my appearance at the hearing wasn’t necessary, but since I’d not yet received the negotiated assessment in writing, I wanted our agreement to be put on the record.

When the assessor expressed surprise that I’d appeared, I said, “I’m simply here in keeping with the adage, ‘The world is run by those who show up.'” This made him laugh, which woke up the four people.

With everyone now fully alert, my objective to confirm our agreement was easily accommodated.

As I drove the dark winding road 7.5 miles back to the Red Cabin, I reflected on the contrast between this easy disposition of my objection this time around and the proceeding 25 years ago. Back then a different assessor had slapped the Red Cabin with a premium for “new construction” (the dwelling had been completed just four years before). He’d done the same all around the three big lakes in the township—Round, Grindstone and Lac Courte Oreilles. Property owners were incensed, but few were successful, since everyone’s assessment had been jacked up by a consistent margin. I took a different tack.

I remember the proceeding well, though I don’t remember if my lawyer—me!—was wearing a baseball cap or not. If I were to guess, I’d say, “Yes,” but there’s no guessing about the rest of my attire. I definitely wasn’t wearing a suit, but then again, no one else in the crowded hearing room was either.

The proceedings were to be recorded by an old portable battery-operated cassette machine, which the chairman placed at the center of the table separating me and the three board members. After punching the record button, he told me I could proceed. Seeing that the red recording light was on, I plunged into my spiel.

My argument was a long shot, I knew, but I took the position that although the framing and exterior of the Red Cabin, the mechanicals, plumbing, wiring and a good portion of the interior finishing were brand new, many of the materials and fixtures had been “repurposed” from other sources.

The entire downstairs flooring, for example, except for the mud room area, was pine planking from an old warehouse in western Pennsylvania. The wood had been reclaimed by a guy in Somerset, Wisconsin, who was in the business of recycling lumber. He’d planed and sanded the wood and cut tongues and grooves along the edges. He then hauled the planks up to Red Cabin and stacked them on the back deck. One by one I carried them inside and over a week’s time installed them myself.

From the old log cabin that we’d razed and replaced with the Red Cabin, I’d pulled enough roofing boards to have planed and sanded and hauled back so I could use them for interior walls of what would become a small den. From that old cabin I’d also extracted rafter poles, which were later tooled into spindles and railings around the loft of the Red Cabin. Split rocks from the fireplace chimney of the log cabin I incorporated into the hearth on which our wood burning stove was later installed, and an exterior light from the log dwelling was transfigured into an interior light inside the new place. The rear exterior door of the log cabin I converted to a pocket door for the downstairs bathroom of the Red Cabin.

The bedroom and upstairs bathroom doors I designed and built myself out of the same lumber stock as the flooring.

The kitchen cabinets were hand-me-downs from Beth’s brother and his wife, who at the time were remodeling their kitchen.

The large pine post supporting a corner of the loft inside the Red Cabin had been a beautiful tree not far from the old cabin of Björnholm—until a windstorm snapped off the trunk 10 feet up from the base. After Dad cut it down, Garrison and I rolled it down the slope to the lake and floated it down to the Red Cabin building site, where again, I had it kiln-dried, tooled and installed.

One winter weekend during construction, Dad assisted me in nailing the old roofing boards—now wall covering for the den. He tied on a carpenter’s apron and went to work in his usual focused and expertly meticulous way. At some juncture during the effort I grabbed my old Instamatic camera and called out, “Hey, Dad!” When he looked up, I snapped the shot. His countenance reflected surprise and projected an uncharacteristic impression of advanced age.

For exhibits I displayed for the Board of Review photos of all the used materials and the Instamatic snapshot of Dad the carpenter who, stooped to nail in place a board two feet off the floor appeared to be 20 years older than he was at the time. I also laid out some of the scraps from the “repurposed” materials.

It was at about that juncture in my presentation when I looked down at the recorder and noticed that the cassette wheels weren’t turning. I had no idea how long they’d been stationary. “Uh, excuse me,” I interrupted myself, “but I think the tape reached the end of its rope, so to speak.” The chairman pulled the recorder closer, popped it open and confirmed that yes, in fact, the machine wasn’t recording. He unceremoniously flipped the cassette over, closed the lid and pressed the recording button. “Now we’re in business again,” he said.

I didn’t have to think much about not objecting to the gap of unknown duration in the record. In the first place, I’d planned to lay it all on the line at the hearing and not bother with an appeal to the circuit court if my effort before the Board of Review should fail. Moreover, to go “city legal” on these three guys in their Northwoods flannel shirts would not be a smart tactical move.

I proceeded to my closing argument, which comprised two simple sentences: “As you can see, gentlemen, old materials and an old carpenter do not make for new construction. Therefore, the new construction premium included in our reassessment should be discounted by at least 50%.”

To my considerable surprise, the Board agreed—and afterward, out in the parking lot, several taxpayers wanted to retain me to handle their cases. I declined, knowing it’s best to quit the town hall when you’re ahead.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson