JULY 8, 2019 – From August 28 to September 13, 1981 my travels led to Poland. For a year that country had been in the news—Solidarność, the illegal workers union, had started a revolution against the Communist regime, and the world watched nervously to see how the Soviet Union would react. Would it invade and quash the uprising as it had crushed other rebellions over the years? Or would developments in Poland spread across Eastern Europe, threatening the viability of the entire Soviet Empire? As a news junkie even back then, I had to see for myself what was happening “on the ground.”

Prior to my arrival, I knew little about Poland besides the fact that Polish immigrants had found their way to “Nordeast” Minneapolis, keeping tidy houses in working-class neighborhoods. By the end of my sojourn, having talked in depth with more than a 100 Poles from all walks of life, I emerged from a crash course in Polish history, recent, less recent, old, and ancient.

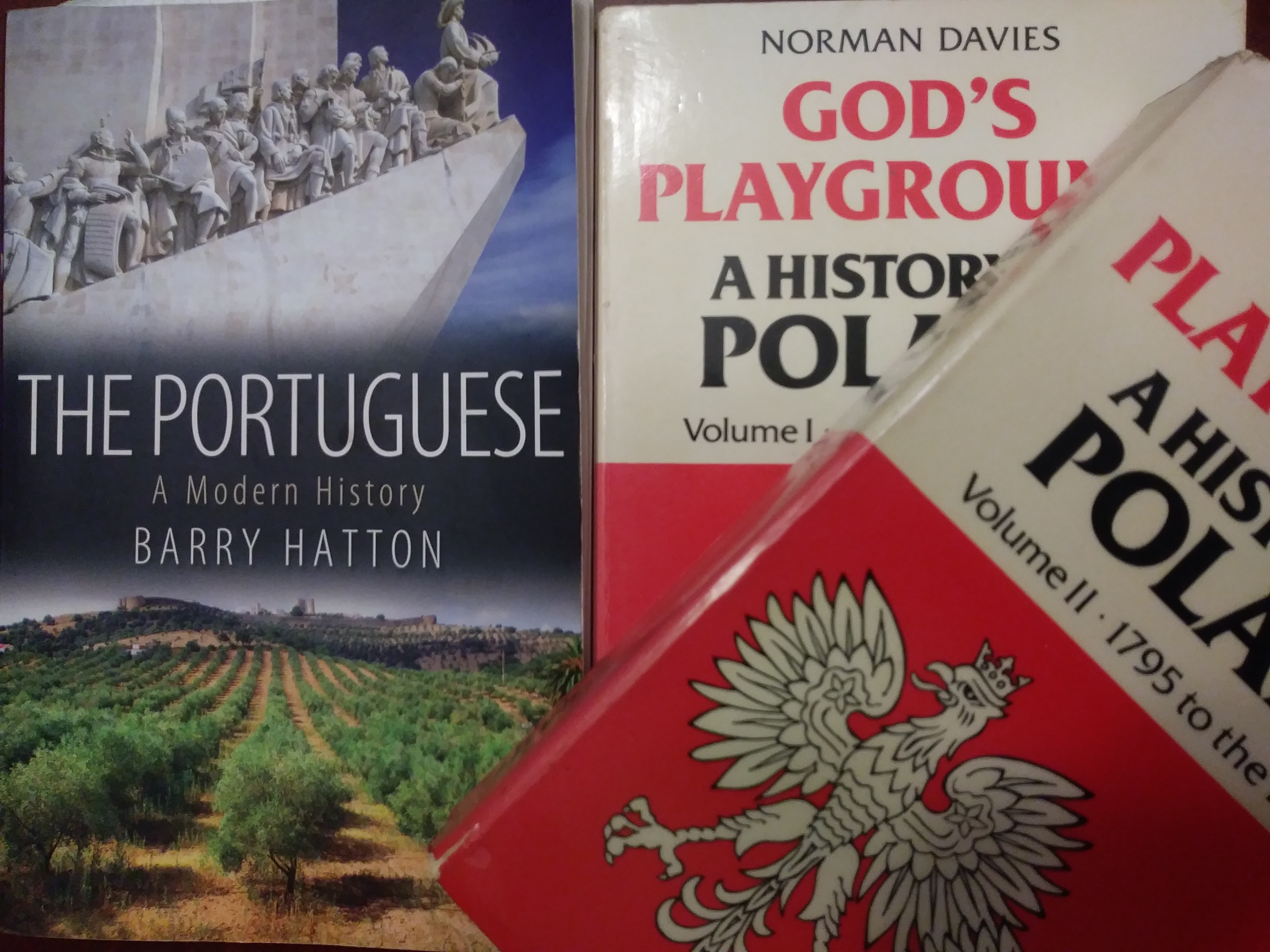

With piqued curiosity I later bought every book I could find on Polish history. Every one of the books paled compared to the two-volume definitive history by the British scholar, Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland. His work was the most in-depth treatment of any national history I’d ever encountered.

Davies started by asking how one should define Poland. As he went on to explain, the answer was elusive if not impossible. But I forged ahead through a 1,000 years of “Polish” history, and I was handsomely rewarded for my efforts.

Like a person with whom I’d traveled on a long, arduous journey, Poland—with all of its high points and low ones; its warts—and worse—and nobility; its quirks and wonders; its death and transfiguration; its contributions to the world of art, music, learning—Poland was no longer the curious stranger it had been upon my first step off the boat from Sweden.

Norman Davies was my hero. With an even hand, he had guided me meticulously and intelligently across the interwoven threads of a grand historical tapestry. His work left me with what I felt was a reliable, balanced image of “Poland.”

Fast forward to June 2018. With my younger son’s engagement to a woman of Portuguese heritage and strong ties to her parents’ homeland, my curiosity about Portugal recalled my fascination with Poland.

This time my guide was another Brit—Barry Hatton—a journalist based in Portugal for 20 years and married to a Portuguese woman. His work, The Portuguese / A Modern History, though much shorter than Davies’ tome, is every bit as insightful and captivating. I’m now reading it again.

I’ve come to see Portugal as a complex drawing; a portrait of sadness, tragedy, hope, and happiness; of languor, ambition, cruelty, and warm civility. To my own observations, Hutton has added color, nuance, and narrative.

When you visit a country, you make its acquaintance. When you read a good history, you can better say, “I understand.”

© 2019 Eric Nilsson