DECEMBER 14, 2023 – (Cont.) While listening to the Bartok on the drive to the Red Cabin, I reacted as I always have when listening to a “war horse” of the violin repertoire[1]: “Hmmm, now that passage [or movement, even] I could play . . . with a little practice” and . . . “Uh oh, now this passage is definitely forbidden fruit. I’d hurt myself even trying to master it.”

As I engaged in this “could play” and “couldn’t play” exercise, I realized how the impossible parts of the thoroughbreds—pieces that musically are great works of art[2]—had rendered the playable sections off limits throughout my musical career (as it were). It was as if I’d never be allowed to ski any of the amazing runs at Whistler (British Columbia) because many are triple-black diamonds.

What was to prevent me, I thought, from getting my hands on the music of a number “war horses” and learning the parts that were reasonably within my capabilities? But, I had to answer, for what objective? My own gratification in the limited confines of my practice room? What’s the point of making music if not to perform it in some setting in front of some kind of audience? (Actually, in my personal experience a rather big point exists, but that’s for another essay.) If it’s reasonable to learn to play the more accessible passages of “war horses,” it’s just as reasonable to perform them.

This perfectly sensible (I thought) conclusion, however, led to a quandary: under what circumstances does one “perform” bits and pieces of great music? The answer lay in my very phrasing of the dilemma: “bits and pieces”—except I switched out “and” for “of,” giving me, “bits of pieces.” Voila! I could see the “show” title; the playbill; the promotional line. Given that my traditional musical forte has been on the promotional side of my actual performances, I could have a blast playing the possible.

As with any challenging pursuit, of course, the devil wallows in the details. What would it take to produce what was beginning to take shape in my mind? If the devil always relishes a role in the plans of mice and men, the devil can be chased out of town by hard work and . . . the proverbial village working in concert to . . . raise the village. Another way to describe the process is “connecting the dots.”

In the case at hand, as I identified and connected the dots, I discovered purpose and motivation that went far beyond the music.

The first dot, of course, was my long-time piano collaborator, Sally Scoggin. The second dot was my close friend and with Sally, a co-director of the Regions Hospital Foundation, Linda Lovas Hoeschler. The third dot was the Foundation itself and contacts that I’ve cultivated there over the past year. The fourth dot was HealthPartners oncology department at Regions, where I’ve received world class treatment for the past two years, and where Linda’s late husband Jack—a close friend of mine—had also been treated, which department engages in cancer research funded by the Foundation[3]. The fifth dot was my good friend Dr. Ravi Balasubrahmanyan, a family clinic doc who took it upon himself to study my disease and its treatment protocols so that he could hold my hand psychologically through the darkest days following my diagnosis—calling me every single evening after work for close to four months to check in on me. The sixth dot was my good friend and past musical collaborator, Lydia Lui, whose husband knows my oncologist, Dr. Kolla exceptionally well.

On the heels of a Foundation board meeting, Linda told Sally that she, Linda, and her husband Peter (see 5/4/23 post) would be open to hosting a recital by Sally and me. Over lunch with Lydia in September, I connected the dots, which formed a beautifully perfect circle . . .

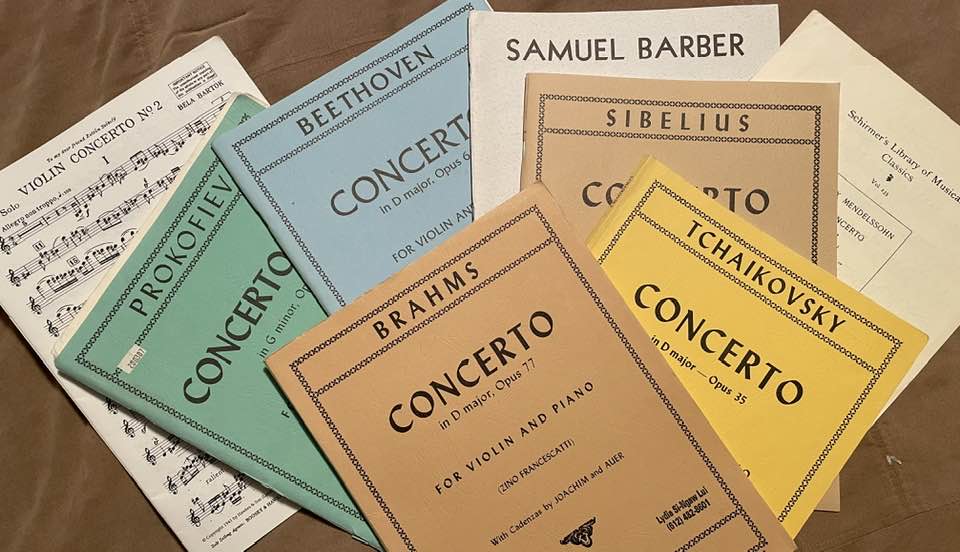

. . . We’ll produce a show at Linda and Peter’s, called, “Bits of Pieces.” The theme will be “Gratitude” for the health care angels in our lives who go around masquerading as mortals. With Sally providing piano reductions of the orchestral parts, Lydia and I will take turns performing excerpts from 10 or so “war horse” concerti. (To lighten the stampede, we’ll rely on long-time participant in the “Fiddler Under the Roof” series, Liz Cutter, to play excerpts from Mozart’s flute concerti.) Finally, after all these years, I’ll “perform” parts of the Mendelssohn, the Sibelius, the Tchaikowsky, and the Bartok[4], while Lydia fills out the thoroughbred war horse sampler with additional excerpts.

This approach to the greatest of violin concerti has already taken me to musical vistas I’d never before experienced firsthand (the Mendelssohn excepted). But those are mere views of bonus land. Since my goal is the expression of gratitude, I don’t need or expect the angels in the crowd to say, “Bravo!” I simply want them to hear me say “Bravo!” for their care in the best way I can—by sharing samples of really great music performed to the limits of my ability. Nothing else has ever motivated me to practice my violin harder, smarter, and longer.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] The “war horse” stable includes all the major pyro-technical (virtuosic) concerti—the Beethoven, the Brahms, the Barber, the Sibelius, the Tchaikovsky . . . you get the drift: since each of the foregoing composers wrote only one violin concerto, everyone in the know refers to the sole solo work by the shorthand “the,” as opposed to a formal description along the lines of, “Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in D Major, Opus 61.” Tell a person you heard so-and-so violinist play “the Brahms” would be enough to identify the concerto performed. The “war horse” stable also includes, of course, concerti by composers who wrote several, though often only one gets any “air time” (e.g. Nicolò Paganini’s concerto in D major (the first of six); Max Bruch’s concerto in g minor (the first of three); Camille Saint-Saëns’ concerto in b minor (his third of three); Bela Bartok’s concerto no. 2 (of two); Bartok, by the way, was fascinated by folk music and devoted considerable time and effort traveling throughout corners of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire researching folk music. His compositions reflect a heavy influence of his interest in traditional music styles.). Then there’s Sergei Prokofiev who wrote two “war horse” concerti, both of which are performed regularly. Also in the stable are non-concerti virtuosic pieces such as Max Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy, Saint-Saëns’ Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Maurice Ravel’s Tzigane and Pablo de Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen (to name a few).

[2]The Brahms and the Beethoven being the leading examples; Paganini’s (first) concerto and Sarasate’s Zigeunerweisen representing pyro-technics in ascendance over musical refinement.

[3] Included will be members of the BMT (“Bone Marrow Transplant”) team at the Masonic Cancer Center at the University of Minnesota.

[4] Given the greater popularity of Bartok’s Violin Concerto No. 2 over No. 1, the former can be readily identified as “the Bartok.”