APRIL 6, 2022 – Well after suppertime, I boarded a train in Malmö for the hour-long trip to Ystad at the very southern tip of Sweden. There I boarded a Polish ferry bound for Świnoujście across the Baltic—formerly the German city of “Stettin” before the westward re-arrangement of Polish borders after WW II.

Nearly all the ferry passengers were Polish, and they carried large quantities of food stuffs purchased in Sweden and unavailable in Poland. The people looked exhausted, and I suspected that they’d made the trek to Sweden solely to re-supply their kitchens and had forgone sleep for a day or two. Sprawled along every corridor and open space aboard the ship, the Poles looked like reverse refugees—tired and forlorn, heading back to their country*.

My first sighting of the Polish coastline was six hours after our departure from Sweden. As the vessel docked, I could see that I’d traveled to a starkly different world: on the railroad tracks all around the port were old-fashioned, smoke-belching, coal-fired steam engines. And everything looked run-down and covered with coal dust—in marked contrast to neat, orderly, prosperous Sweden.

So began the most intense phase of my entire odyssey. Such a torrent of indelible impressions saturated my brain that immediately upon my return to Sweden 17 days later, I sat down with my notes, drew up an outline, sketched out a report, and on my cousin Merith’s typewriter, hammered out a 13-page, single-spaced letter home.

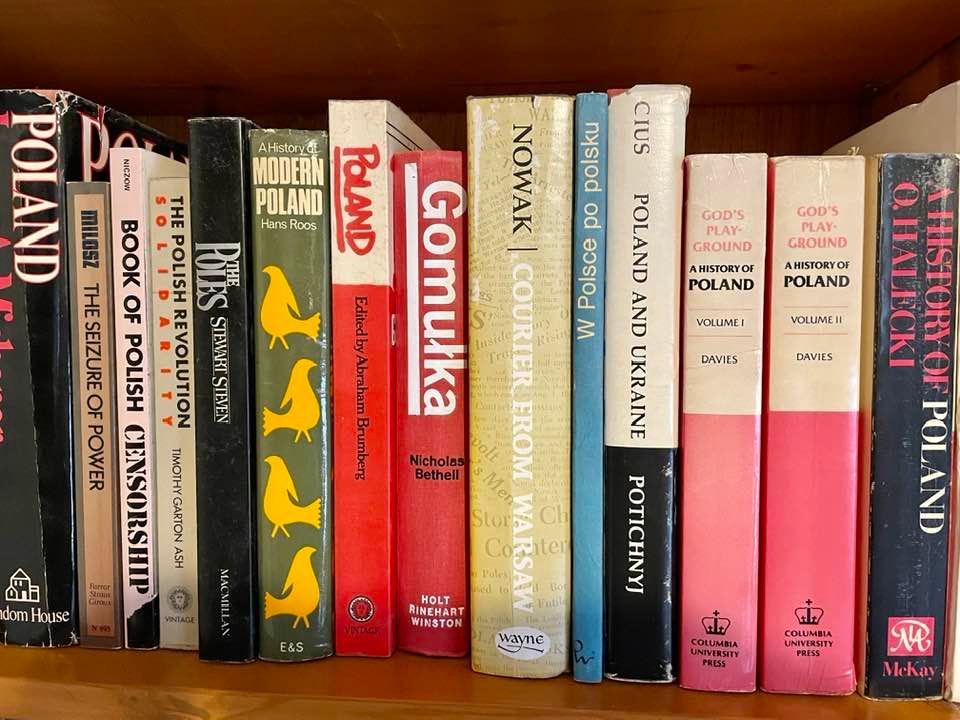

My sojourn in Poland sparked an interest that dominated my thoughts long after I’d left the country. I plunged into Polish history, devouring every book I could find on the subject. I even considered graduate school to pursue my newfound interest vocationally—as an academician, a specialized journalist, or a foreign service officer. The explosive state of the country at the time, combined with many months of travel experience, allowed me to optimize a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I seized more from my encounters in Poland than I’d commandeered anywhere else. I saw myself not as a tourist but as a free-lance journalist, observing closely everything that could be apprehended along my path.

Such an experience is a challenge to recount. Details are the foundation for generalizations, and throughout my encounters in Poland I discovered links between observable, recordable particulars and the validity of broad impressions.

Take, for example, the supreme question of the day: what would ensue if the Russians invaded? I posed this question to “Leszek,” whom I met on a train; a Communist Party member and tank commander in the Polish Army—the profile of someone ostensibly loyal to the Communist regime. But when I asked him what he would do if Russian tanks rolled westward, he said spontaneously—and without fear of repercussions, “It is my duty to fight Germans, but it is my pleasure to fight Russians.” This told volumes about the potential risks faced by the USSR if it invaded Poland.

Tomorrow’s post—and many more—will dive far below the surface of the most important news story of 1981.

______________________

*In contrast with surrounding Communist countries, Poland had recently adopted more liberal policies regarding exit visas.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson