JUNE 2, 2024 – In ancient times I was involved in a case concerning a prominent piece of real estate in downtown St. Paul[1]. For years the matter consumed a plurality, sometimes a majority, of my billable hours at the firm. Other lawyers with the pertinent client relationship that predated my hiring had reeled the case in, but they’d tired of the many impasses on multiple fronts. Each of the wide red-rope folders that the case had already generated was filled with overstuffed manila folders labeled, “Pleadings I,” “Pleadings II” (and so on), “Notes to File – [month of inception],” “Notes to File – [current month; and so on],” “Invoices,” and a dozen other generic categories. Lucky me.

A year or so into the matter, I found myself in the Ramsey County Courthouse, arguing in favor of a motion—or against someone else’s (the case involved multiple parties), I forget which, since the motions of one sort or another were a regular aspect of the case. I rather enjoyed making the treks from my office in Minneapolis to the courthouse in St. Paul, which at the time had a vibrant downtown dominated by commerce and normal folks on the bustling streets, not today’s scene (I’m told) featuring ne’er-do-wells gathered on largely empty streets avoided by normal folks.

In any event, the motion concerned a substantive issue with implications for the broader cityscape, not merely the subject property, and so, a couple of reporters in the employ of local news organizations were on hand. Again, we’re talking ancient history here—when such organizations commanded the readership, audience and corresponding revenues to support full-time trained journalists reporting on local newsworthy matters—a key function of the Fourth Estate in a vibrant democracy.

After the protracted hearing, during which the patient and intellectually engaged judge gave each of the half-dozen lawyers at least two bites at the apple of justice, I was approached by one of the reporters, a guy who’d attended previous hearings and who, I knew, worked for The St. Paul Pioneer Press back when it was a real daily paper worth one’s time, respect, and attention.

I was wary, of course. Absent lots of trust in the phrase “off the record,” I had to assume that every word I said would appear in print. Therefore, I couldn’t reveal any client confidences or make any statement that could be deemed an admission or that might reveal a litigation stratagem or otherwise prejudice my client’s interests.

On the other hand . . . the case was complicated, and in the course of handling it, I continually encountered perceptions and positions that were fundamentally incorrect, both factually and as a matter of law. For example, certain public officials and members of the public believed that my bank-client should be a “better corporate citizen” and show more willingness to “compromise” on the unpaid debt of the failed renovation project that was at the heart of the litigation. What those critics didn’t understand was that my client was merely the indenture trustee for the publicly held bonds that had financed the historic landmark rehabilitation project. As trustee, my client had a duty to the bondholders—not to members of the public or . . . the city council.

Accordingly, I figured it couldn’t hurt but would help if I explained some of this to the reporter. I wouldn’t reveal anything that wasn’t widely accessible public information. I’d simply endeavor to educate the reporter in simple, perfectly understandable terms so that he’d have an informed context in which to review his courtroom note-taking and the ultimate script of his article.

In the moment, I felt as though I’d made the right decision. The reporter seemed genuinely interested in improving his own understanding of the matter. He asked pertinent questions that reflected his ignorance of critical elements of the case, yet the corresponding need for me to address the gaps in his knowledge. He took copious notes, much in the fashion that an associate (in those days) at a big law firm dutifully jotted down every word that a senior partner was imparting about the matter that said partner was handing off to the associate. Vis-à-vis the reporter I assumed—much as a senior partner passing information along to an associate—that the reporter had the skill appropriate for his task.

Two days later the article appeared. Fortunately, it wasn’t on the front page—the main front page. I cringed when I read it. The piece omitted material facts and included numerous materially erroneous statements. The overall impression the article gave of my client was that it . . . simply wasn’t a very good “corporate citizen.” Why had he not given me a chance to review the article before it had gone to press?

At the time I felt scandalized, so much so I phoned the reporter to ask him how much ear wax he’d removed since our conversation after the court hearing. His response was depressing, filled as it was with evidence that he’d flunked my 10-minute tutorial on how bond issues work and the rudiments of real estate law. For the rest of the day what rang in my ear was his repeated phrase, “But I thought you said . . .”

In time the case was concluded, and I moved on. If I kept a copy of the article it was shredded along with the file years later (but still in a year B.C.E.)

The lesson I learned, however, stuck with me. And no, it wasn’t, “never talk to a reporter.” (Little did I know that in late 2017 and for much of 2018, it was impossible to avoid talking to reporters—and being quoted by one in The New York Times—again, without assurance of accurate reporting.) No, the lesson was this: If a news article by a trained, professional reporter got nearly everything wrong concerning a matter about which I had intimate, first-hand knowledge, grasp of context, background, and necessary framework by which to evaluate facts (and opinions) . . . surely thousands of other news stories on far more complex issues about which I know far less contain material inaccuracies.

And mind you, this “lesson” came eons before the Age of Steroidal Misinformation.

As I ponder the lesson today, I appreciate its fuller implication: that as we navigate through the best of news reporting (and much is of very high quality), rarely if ever do we have a handle on all the material facts; and even more rarely, even on the occasions when we do have a grasp of a robust slate of facts do we have sufficient understanding of context, background, and technical/historical information to reach an accurate conclusion about the facts.

If in a matter about which I have the fullest understanding possible of facts and framework alike, a newspaper account gets everything sideways and upside down, what of news reports of issues about which I know precious little of all that should be known to reach an accurate, well-informed opinion? Take the economy, the environment, public health and safety, the power grid, technology, international relations. Consider how much must be known about each of these areas and many more, yet we have neither time, patience, nor aptitude to learn and synthesize all that must be known to reach a viable opinion.

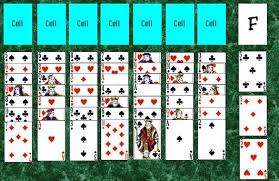

Throughout our lives—most pointedly in the voting booth—we make hugely consequential decisions without knowing and understanding all that we should. Each of us plays an unending series of solitaire in a communal hall, but none of us plays with a full deck. Aggregate all the solitaire players, and what do you get?

. . . A democracy in which we grouse continuously that the game is rigged.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] The Union Depot Place, now serving as the recently (and beautifully) renovated Amtrak station from which my wife and I will soon depart with our eight-year-old granddaughter on a splendid train trip to the East Coast.

2 Comments

Nicely written. So much so, I am forwarding the link to your post today to Lisa, my daughter, AP History teacher at Mounds View HS, to consider sharing with her class. Imagine how much of History has been jumbled. Are knowledge and truth even close to synonymous?

Connie, I’m so impressed that Lisa is an AP History teacher–and at a great school, too! It would be grand to chat with her about her perspective on the generation she’s teaching; her insights, highlights, low-points. Bully for her!! (“Students of History, Unite!”) — Eric