SEPTEMBER 3, 2024 – (Cont.) In anticipation of our mini-reunion with Carol and her husband Barry, Jenny and I talked about things we could do and places where we could dine out.

On our list were “Anna’s house” two doors down, where Anna and her husband Mickey lived. They were shirt-tail relatives of ours, though none of us could remember exactly what the relationship was, just that “Anna” was a kind older woman and that Mickey had been an engineer who’d worked on the Panama Canal before retirement. Carol had told me on one of our phone calls that as a little kid, she’d spend time at “Anna’s house,” as had Jenny and I. Anna and Mickey died a long time ago, but the current owners were happy to accommodate a “reminiscence visit.”

Other possible reunion activities:

- Kayaking on the cove for a sea-level perspective of our ancestors’ perches on the high bank above.

- To or from the Hamburg Cove marina, we could peer through the plate glass windows of Reynolds General Store—closed and unoccupied for seven or eight years but when we were kids, the sole retail establishment on the cove and just down the hill from the Holman properties. The store had always been about 30 years behind the times and was run by a tightly wound older woman of the locally dominant Reynolds clan.

- A tour of the Lyme Art Association center and the adjacent Florence Griswold museum featuring the works of American Impressionism depicting familiar scenes from the Lower Connecticut River Valley.

- The Connecticut River Museum in Essex and from the adjacent wharf, a cruise on the Onrust—the replica of the original Dutch ship built in 1614 under the command of Adriaen Block, the first European to chart the Connecticut River 60 miles upstream to what is now Hartford.

- A ride on the Hadlyme-Chester ferry along with a stop at Gillette Castle State Park overlooking the Hadlyme side of the Connecticut River.

- Most important, perhaps, would be the Ely Family Cemetery—a mile and a half from the cove—where Ichabod Spencer, our great-ditto-ditto grandfather the Revolutionary is buried.

Except for the cemetery visit, however, all plans and possibilities for local points of interest were wholly displaced by our animated, deep-dive, non-stop conversation. After two days, everyone knew that we’d but scratched the surface. We realized that as much as we’d been “family” to this point in our lives and would always remain so, from these short two days we’d be friends for the rest of our lives.

Our connection deepened as we told our respective stories as well as our respective versions of the same story: the relationship between our grandfathers and the unfortunate split of their thriving business and the irreconcilable rift it produced between Carol’s father, on the one side, and my/Jenny’s uncle on the other; the emotional crater produced by the untimely death of Carol’s uncle, who was Mother’s closest friend, cousin and mentor every summer at the cove; the cheerful swimmer-sailor who taught her how to rig a sailboat, paddle a canoe and kayak, and how to skipper a powerboat.

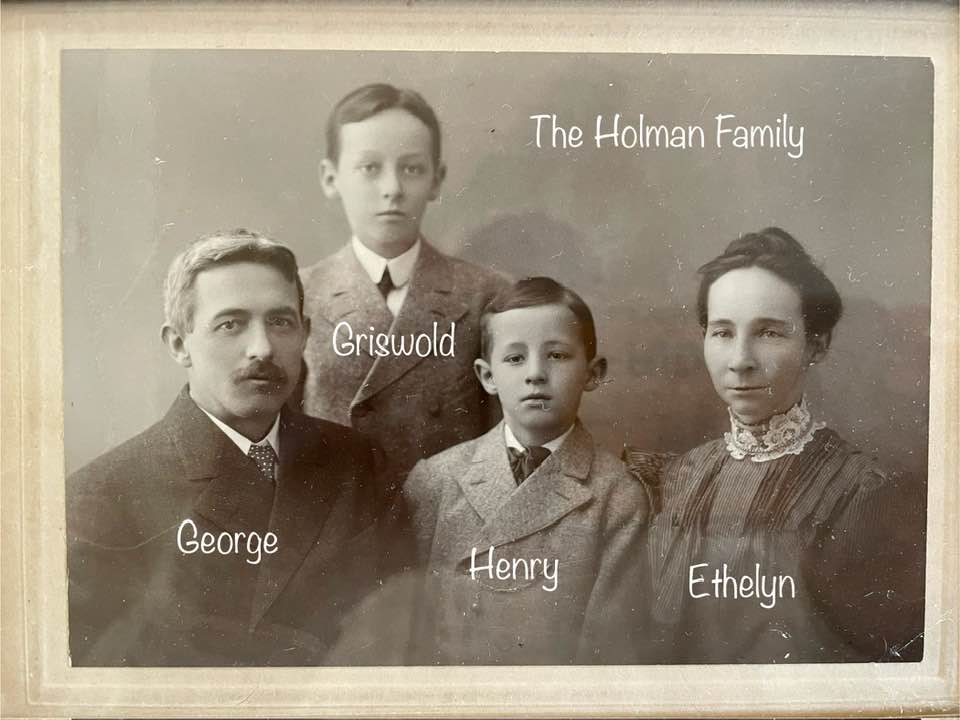

We discovered many things about our two sides of the family—the Griswold half (our side) and the Henry half (Carol’s side). Some of these discoveries assumed more the character of revelations. Take, for example, the central tragedy of our shared family history: the death of Carol’s uncle in WW II. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Robert Bruce Holman, oldest grandchild of the grand patriarch of the family, George B. Holman, was a junior at Dartmouth and captain of the swim team. He was the clear leader of his generation of Holmans; a charismatic young man full of promise and opportunity to leverage that promise; a person loved and admired by all, destined to lead the family business to ever greater growth and success.

When his B-17 went down, it crushed his mother’s heart. As a young girl Carol was told that her grandmother had been incapacitated by “a stroke,” when in fact, as later revealed, it was a mental breakdown. What I’d never considered until our reunion with Carol, however, was the effect that the loss must’ve had on Carol’s own father, Robert’s younger brother. They were about five years apart, and when the older brilliant son/brother with so much potential perished, the surviving son/brother must’ve felt what was in many ways an unbearable burden: How to fill such big shoes, especially against the backdrop of his parents’ grief? How now—and for the rest of his life—to measure up?

Carol’s father was no shrinking violet; quite the opposite, at least as I recall from my numerous encounters with him but only when I was very young. How much of his outward behavior and more important, his psyche, subliminal strivings, emotional condition were affected by his brother’s heroism and death?

For the first time I considered the parallels between the impact of Robert’s death on Carol’s father and the effect that my mother’s stature had my uncle. Uncle Bruce had been a sickly child, coddled by his mother and largely ignored by his father, not only in Uncle Bruce’s formative years but throughout his life. Even though the two men lived under the same roof until Grandpa died at 93, they were oil and water, and most of the time, it seemed, the water was ice. How much of Uncle Bruce’s abnormal disposition—including his chronically irascible attitude toward his sole surviving Holman cousin—was the manifestation of an inferiority complex in the face of my mother’s shining successes from her earliest days. She skipped a grade in elementary school. Though she would always be a year younger than Uncle Bruce, they’d always be classmates, as well, and invariably compared as such. In every avenue of their lives—academics, extra-curricular, socially—Mother was to the “Griswold” side of the Holmans what Robert had been to the “Henry” side. The comparison between Mother and Uncle Bruce culminated when in high school Mother was voted as “The most likely to succeed.” Grandpa certainly thought so: in his mind, rapport and moral support, Mother was clearly the favored child. Like Carol’s father, Uncle Bruce wasn’t shy or retiring. But how much of his outward behavior was simply a cloak over deep insecurity? And, I wondered, what was Uncle Bruce’s long-term psychological reaction to the death of his older cousin, star of the family, given that Uncle Bruce’s spent most of the war at Fort Benning (renamed Fort Moore, when it was more widely learned that Benning was a Confederate general) where his most notable service was taking care of the commandant’s dog while said commandant was away on business at the Pentagon?

Our wide-ranging reunion conversation highlighted other parallels besides Carol’s father and Uncle Bruce each living with the inevitable and tough comparison to a sibling. The most prominent similitude was the role of interlopers in disrupting family dynamics; on “our side”, a gold-bricking suspected drug-addict on “our side” helping himself to over a million in cash by preying on the emotional needs and psychological aberrations of Uncle Bruce; on Carol’s side . . . here, unfortunately, I must leave my readers in suspense, for now at least.

And then were the clocks. Yes, the clocks, which appeared three times in our family history, not in parallel but as might be described as a “parallax error.” Innocently enough I asked Carol if she knew who in the family might’ve collected antique mantle clocks of the sort I discovered years ago in a closet on the third floor of my grandparents’ (and before, our great-grandparents’) house. She responded by a fascinating story about her grandfather—our side’s “Great Uncle Henry.” Early in the development of the family moving and storage business, Henry, apparently, had become an auctioneer, a practical skill when it came to disposing of abandoned or forfeited storage lots. In the course of his side-work as an auctioneer, he became a clock collector, and over the years, Carol said, he amassed an enormous collection of all kinds of clocks. He dedicated an entire room of his and his wife’s house to the display of his collection, and on the occasion of holiday visits by Carol’s family, Henry would wind up his favorite clocks and set them in motion for his grandchildren as they were ushered in and took their places on the steps leading down to the recessed floor of the “Great Clock Room.”

How a dozen or so clocks wound up at 42 Lincoln Avenue (the grand old “fortress” in Rutherford, NJ built by our great-grandparents) is anyone’s guess. Given that they had become a kind of “abandoned storage,” I can fairly conclude that my grandfather did not share his brother’s keen interest in clocks. As if by divine symbolism, the stored clocks so long-forgotten were destroyed in the fire that destroyed the grand house under the abysmally irresponsible stewardship of Uncle Bruce.

Uncle Bruce, ironically, was himself a clock collector of sorts. Jenny and I laughed at the thought of this as we explained it to Carol. One of our uncle’s innumerable quirks, fetishes, obsessions, and infatuations involved . . . clocks. But not the rare, ornate, fascinating clocks that were comprised by Great Uncle Henry’s collection. By the dozens Uncle Bruce acquired cheap plastic timepieces on sale at K-Mart or other discount stores. Often he wouldn’t bother removing the clocks from their packaging. He’d simply nail them to the walls of each room of 42 Lincoln that he occupied after he assumed control of the place, as well as in his sprawling, junked out “suite of offices” in the adjoining warehouses.

As much as I wish I could’ve shown Carol firsthand, Uncle Bruce’s clock manifestation of his abnormal psychology, I wish far more that I could’ve seen her grandfather’s remarkable collection.

Late one evening the conversation turned to what became a central part of Carol and Barry’s story. She’d told me a fair amount about it over the phone, but to hear it again and in greater detail framed it in a deeper, broader perspective. Their story’s parallel to a critical part of my own story was yet another piece of our newly united family story. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson