FEBRUARY 8, 2021 – I’ve been living in a cave. Forever I’d heard of the landmark film, The Birth of a Nation and its racist reputation, but until last week, I’d never watched it. Worse, I didn’t know what it was about! I’d assumed it was about the founding of America; despite an exhaustive search, I found no explanation for the title of this film about the Civil War and Reconstruction.

My ignorance was inexcusable (a clip of the film had appeared in Forrest Gump, which I’d watched several times), but I’m glad now to be enlightened . . .

. . . On reflection, “glad” and “enlightened” are in conflict with the film’s over-the-top racism.

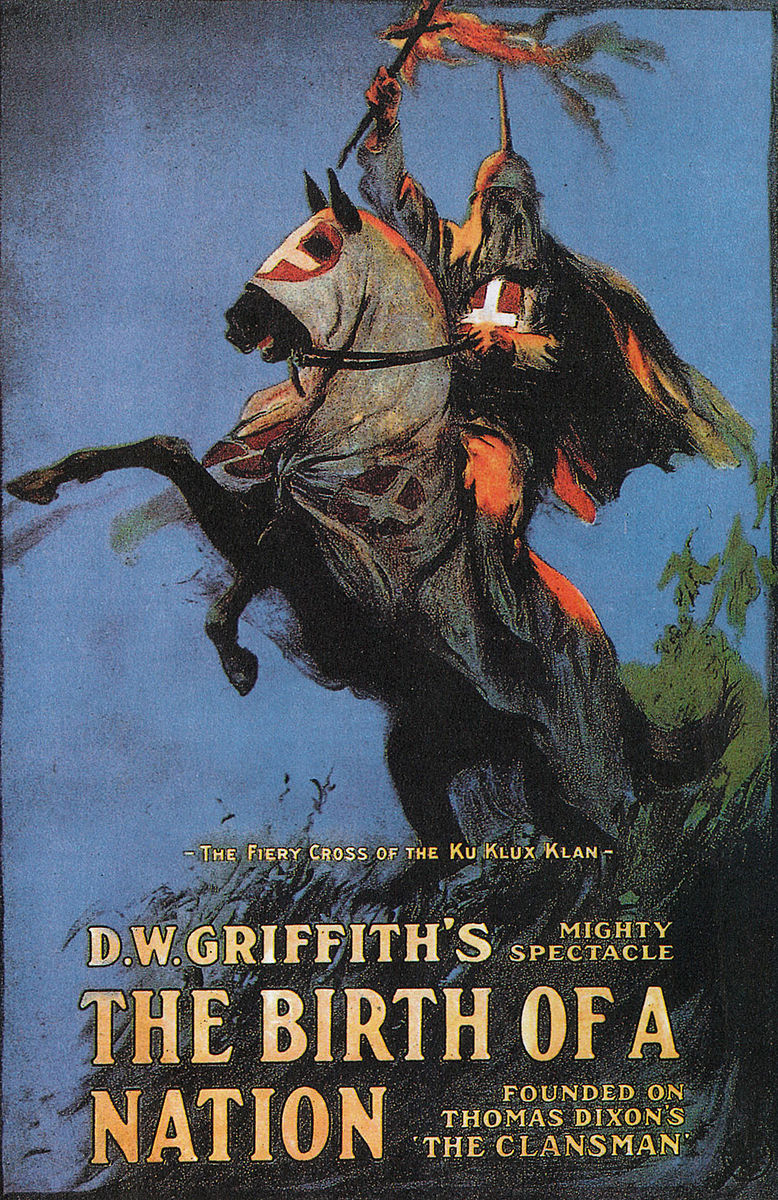

From a cinematic perspective, The Birth of a Nation—originally entitled The Clansman (as in “Klansman,” hint-hint), after Thomas Dixon Jr.’s 1905 novel, which inspired the silent film—was a major accomplishment when it debuted a half century after the Civil War. Directed by Douglas Wark Griffith, it was the longest (over three hours) film ever made, and it was a huge box office success. It introduced new techniques such as close-ups, fade-outs, crowd scenes, and full-scale battles. It was the first film with an orchestra score.

At the center of the film are two families—the Stonemans (Northerners) and the Camerons (Southerners)—whose fortunes and misfortunes become intertwined, first amidst the Civil War and later during Reconstruction. The first half ends with the assassination of Lincoln, who’s treated sympathetically in the film for his conciliatory approach to the South. (In a prior scene, Lincoln commutes the death sentence of one of the Camerons, a Confederate colonel taken prisoner.) The second half is about the “injustice”—in the form of racial equality—that freedmen and Northern opportunists wanted to impose on the white South.

The Stoneman patriarch, modeled after Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens, is a Congressman hellbent on “unleashing” Blacks on Southern whites. The Camerons, meanwhile, must “suffer” the indignities—and worse—of rampaging, ignorant Blacks aided by Northern carpetbaggers.

To the rescue: the Ku Klux Klan—of course! I continued watching, knowing that the film and the attitudes it depicted became a major cultural influence. The experience felt like visiting a bizarre park dedicated to toppled statues of Confederate generals.

Ironically, the film produced two opposing effects. On the one hand, its enthusiastic presentment of the KKK inspired a rebirth of the Klan. Simultaneously, the film’s outrageous depiction of Blacks stirred the NAACP and other organizations to mobilize against racial injustice.

Efforts to ban the film ultimately failed, but in indignation over attempted censorship, Griffith produced another film—the very next year—called Intolerance. That film, even longer than The Birth of a Nation, was likewise one of the most influential among silent movies.

As with statues of Confederate generals, a film like The Birth of a Nation can be a shocking learning experience, however despicable the (lost) cause it promoted. If you haven’t seen it, you should. Being appalled is par for (the history) course—especially this month, Black History Month.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2021 by Eric Nilsson

2 Comments

An amazing film! I just saw it for the first time a couple of years ago and was amazed to read that it was the first movie shown at the White House.

Did you catch the title cards bearing quotations by your favorite president? (They must have been inserted after the WH screening.) What’s most troubling about the film is its net effect on racial attitudes–a proverbial rabbit hole for scholarship and analysis.

Comments are closed.