APRIL 17, 2025 – This morning I woke at 6:35 and looked out the second floor bedroom windows to see what the weather was doing outside the Red Cabin. To my shock and dismay, I saw a gigantic ice floe pushing along our shoreline. Stepping on hot coals could not have spurred a quicker reaction on my part.

“Damn!” I said as I jumped into warm clothes and scrambled outside. On Tuesday I’d driven up to the Red Cabin to take advantage of promising weather for installation of the dock at our boat landing” about 200 feet east of the cabin. All had gone according to plan. By 7:00 p.m. yesterday, the eight-hour job was finished.

As the sun slid toward the horizon, I went for a shoreline walk to work out the kinks in my overworked back and limbs. Far to the east during this stroll, I discovered a massive ice floe—the same one that overnight winds had now blown solidly into our northwest corner of the lake. Knowing what ice can do to any structure built by humankind, I worried that I’d jumped the gun: Would that monster floe cancel my work? Had the ice already done so? Worse, had ice and wind crushed the 30-foot dock and supports into irredeemable wreckage?

I flew down the path. As I raced toward the landing I could hear the waves 40 feet out, crashing against the trailing edge of the floe. The ice groaned under the pressure, like some wounded leviathan of the sea anticipating its inevitable demise.

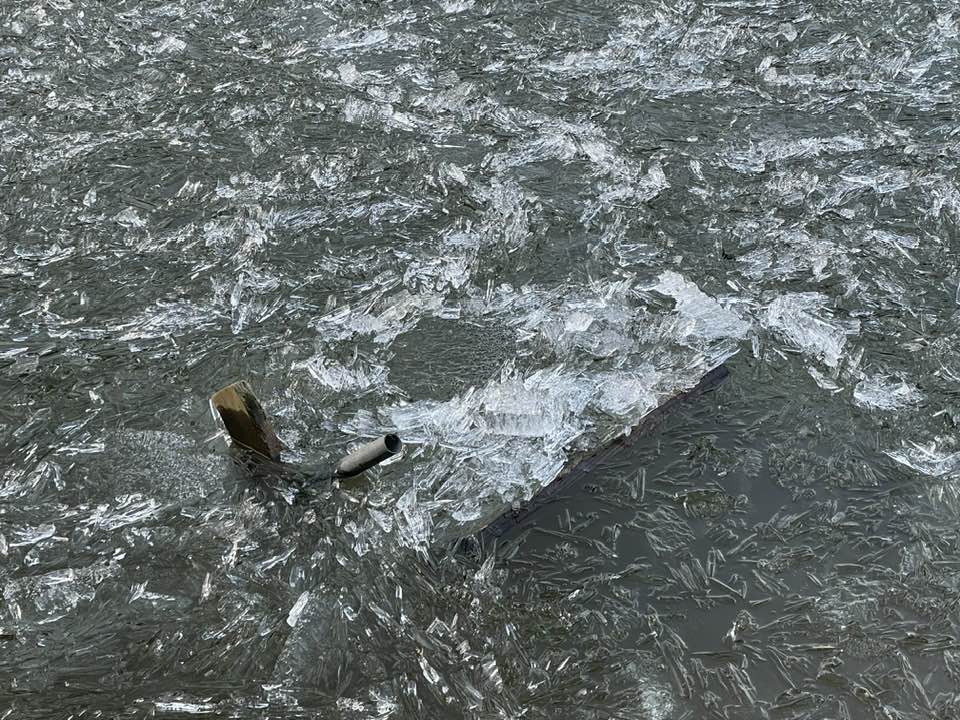

Seconds later I reached the top of the steps leading down to the dock. The result of my hard work was now encased in what reminded me of a gargantuan tumbler overflowing with crushed ice and a trickle of Sprite. A whole third of the dock had vanished, either consumed by the ice or stolen away to unknown points downwind. The auger-tipped 2-1/2-inch pipes that I’d twisted into the lakebed to support the end of the destroyed section were leaning at tortured angles (see main photo). The crushed ice and Sprite washed over the iron braces and cross arms of the pipes as if they were the tips of ship masts marking the site of an arctic waters shipwreck.

I surveyed more of the ice monster seething and heaving off to the west, where angry waves charging across the open water continued under the massive creature. Wind, waves and ice growled continuously, as if in threatening disapproval of my work the day before.

But I wasn’t the only target of their displeasure. Carried aimlessly by the ice was a whole white pine tree, its trunk peeled of its bark and now shining nearly as white as the ice; its dead branches pointed skyward 10 feet or more like the shafts of harpoons stuck fast in the hide of the great Moby Dick. Where that whale of a tree had spent its life, I had no idea: I’m familiar enough with the shoreline within a half-mile in each direction of where I stood to know that that alien tree had traveled several miles.

I launched an immediate search and rescue operation along the top of the shoreline berm, which runs six to ten feet above the edge of the lake. Trees and shrubs blocked my progress as if they were self-appointed accomplices of the ice floe monster. I felt like a spotter aboard a U.S. Navy WW II PBY Catalina, scanning the world below in search of survivors, a life-raft . . . dock flotsam. (Taking off from their perch on a tree branch above me, two bald eagles flew straight out across the ice floe to open water—to scan for food.)

In short order I began to find pieces of dock—a section of decking here; a cross member from the support frame there; a 10-foot long 2 x 6 side piece jutting into the air 20 feet out, trapped by mini-ice bergs; and way down the shore, a four-foot-long 6 x 6 beam.

Just then I remembered the other dock. The brand new one we’d purchased just last year. Yesterday morning I’d dragged two of the 10-foot long aluminum frames into position to take measurements for a set of steps I need to design and build down to the dock once it’s installed. I’d left the frames in the water. When I reached them in the PBY, I found them imprisoned among chunks of ice.

Forget breakfast, coffee, my morning reading session. It was time to return to base to switch modes from search to rescue. I donned my new set of waders, ski hat, waterproof work gloves, grabbed a sturdy walking stick for balance, and returned to the water . . . er . . . crushed ice with Sprite.

The first few items to be retrieved were only a few feet from shore. Easy pickin’s—until I took my third step. I made no attempt to walk on the ice. It wouldn’t have supported my weight even if I’d been foolish enough to try. What I didn’t expect was the force of floating ice cakes pushed irresistibly by the howling wind. With that third step—still another two or three from being within reach of a section of decking—I realized that I’d ventured into a potentially very dangerous situation. Slip on the stones underneath or lose my balance pushing through the ice cakes, and falling into a water depth of only 18 inches could mean serious trouble.

I adjusted my state of alertness to “highest level,” took account of my balance points, converted myself into an arctic ice-breaker with an extra thick steel-plated bow and took two careful strides toward the decking. Then I poked my walking stick in the gap between planks on the decking and slowly pulled the section toward me. I was then able to tow it through the channel I’d made and back to shore. There, steadying myself with one hand on a chunk of ice heaved upward, I dragged the section onto the rocks just above the line of ice.

I repeated this operation half a dozen times, until I scared the crap out of myself by going a little too far and a little too deep. There I learned that a human ice-breaker is no match for ice and wind above a certain (and fairly slight) level. Nature’s forces had closed in on me, it seemed, like the jaws of polar bear. I kept my wits, but it didn’t take much imagination to realize how the whole “rescue operation” could go south (“north”?) very quickly, to where the rescuer would have to be rescued—except who would rescue me . . . in time? I was entirely on my own. I had my phone, but what good would that do (assuming I could fish it out my waders pocket before becoming submerged) except to let someone know where to look for my corpse—until the ice floe monster devoured it? In the next instant I told myself what an idiot I was. In the moment following that, I turned the 2 x 4 I’d just retrieved into a weapon against my “nemiceis.” With all my might I jabbed the five-foot-long wood repeatedly into the ice around me to provide enough room to turn 180 degrees and head back to shore.

Lesson learned. To recover other pieces beyond safe reach, I used my pole saw fully extended. By hooking the curved saw blade onto the dock flotsam, I was able to free the frozen wood, then carefully drag it across the ice floe and onto shore.

It took sheer will and brute force to free the new aluminum dock sections from ice prison. Fortunately, the prison was half ashore to begin with. Freedom was dramatic but less dangerous.

But I wasn’t completely out of the drink yet. With the hope of rescuing the support pipes (the “masts of the shipwreck”), I returned to the portion of the dock that had thus far resisted the onslaught of the ice floe monster. Wading out to the “shipwreck,” I aimed to see if I could salvage the pipes or if the ice had bent them, in which case, at least I could salvage the heavy auger tips. The only way I could manage the mission was to place my hands on the underside of the cross brace—which was right at the waterline—and twist as I pulled.

Bad idea: within seconds my hands were so cold, I could’ve dipped them into a cooler of crushed dry ice and wouldn’t have known the difference. In the next instant I thought of the scene in the Paramount+ series, 1923, in which the (very stupid) heroine freezes her hands and feet, which turn black.[1] I didn’t need mine to turn that color before I’d know serious trouble was . . . at hand. I immediately aborted the mission, left the site of the shipwreck and made a beeline for the dock, shore, and the cabin—100 paces away. I reached the interior warmth of the kitchen—and lukewarm tap water—just in time to avoid anything more serious than short-lived frost-nip. Surprisingly, the exposure hadn’t triggered a Reynaud’s reaction.

After a quick breakfast, I returned to the great outdoors to collect all the dock parts I’d pulled up on about 400 feet of shoreline. Now that my immediate mission was completed and I was out of the water, out of the ice, out of danger, the skies turned dark. There I stood, still tempting fate as I surveyed the giant ice floe, the outer edge of which was still heaving and groaning in the wind-driven waves. In my hand was the pole saw standing vertically, the bottom resting on the ground and the (metal) saw blade towering above me, like a battle-tried halberd.

Distant thunder rolled across the heavens. From an angry sky Zeus hurled a cloud-to-cloud bolt. It was a timely warning to lower the halberd-as-lightning-rod I was holding next to the tall pine tree-as-lightning rod, and head for the relative safety of the great indoors.

Looking out at the approaching storm, I took a breather to assess the overall dock situation. Miraculously, I’d managed to recover all 10 pieces to my “modularized” dock section, plus the beam, and two of the four “feet” that the frame rests on; I can easily make two replacements. The support pipes I can retrieve under more accommodating conditions, or, if they’ve been destroyed, with a bit of effort, I can replace those too. Now it’s the rest of the dock that I must worry about. It stood fast through the day. I’ve checked it every half hour or so, and on two occasions, scrambled to push with all my might an eight-foot-long 4 x 4 beam against incoming icebergs that threatened to re-enact the earlier wreckage of the outer third of the dock. At this writing, the entire ice floe has now moved past the dock to join the grand assembly of ice crammed in the northwest corner of the lake. But before the ice pack melts on its own, will winds blow it back to wreck the rest of my dock and carry the pieces far out to sea?

I decided not to worry about that over which I have no control. Worst case scenario, I’ll have to buy a boatload of Canadian lumber, pay the tariff through both nostrils, and spend a week swatting mosquitoes as I rebuild and install the “modular” dock.

Just after I considered this worst case outcome, I received a news flash about the shootings at Florida State University in Tallahassee—where my niece and her husband teach/work.

In an instant, the possibility of having to rebuild the dock was reduced to little more than one man’s blather over a beer.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1]After months of involuntary separation, Alexandra, Spencer Dutton’s wife, is attempting to reunite with him in Montana. She winds up traveling with two fellow English aristocrats exploring America. They decide to bag the blizzard-slowed train and instead drive a (1920s Ford!) through the blizzard. Dumb idea, especially when dressed as if you’re heading downtown to a symphony concert. The couple freezes to death in the middle of nowhere. Alexandra freezes hands and feet, but is miraculously rescued by Spencer who–get this–just happens to be aboard the train that just journeyed through the blizzard! After giving birth to a premature baby boy (John Dutton), Alexandra refuses amputations necessary to avoid gangrene. She croaks. Typical of “Hollywood winter,” the cold and snow scenes in the series are ridiculous, and clearly the work of writers, directors, cast who don’t know a thing about winter.

1 Comment

As I’m reading these thoughts popped into my head: oh my God, oh my God, what an idiot, oh my God, men, he’s so lucky, why is he doing this alone? Use a rope, pole saw – ah good, always wait until after Mothers Day..

And then the last line…

I’m glad you’re safe.