APRIL 26, 2022 – (Cont.) My initial reaction was that the two guys had been masquerading as Intourist agents but were in fact, KGB. My second was that I’d been set up for entrapment, and I didn’t want to wind up in labor camp in Siberia. My third thought was, Where the hell is my hotel?

When I insisted on being taken there, the guy relented, and after tearing around town, he turned up a street where the Pribaltyska Hotel loomed straight ahead. Before pulling up to the entrance, however, he asked again if I wanted to change money. I didn’t want to risk deportation or being sent to the gulag, but I was curious about the black market exchange rate and whether the guy was legitimately illegitimate or . . . a thinly disguised KGB agent out to nab me.

“What rate are you offering?” I said.

“You have pounds? Dollars?”

“Dollars.”

“How much you change?”

“Oh . . . 50,” I said.

“I give you seven roubles to dollar,” the driver said. (At the official exchange rate one rouble cost $1.30.)

“How do I know you’re not KGB,” I said, “and why only seven? The going rate is 20.” (I had no idea what the “going rate” was.)

“No KGB,” the guy laughed but in a manner that gave me zero confidence in his trustworthiness. “I only do business. See here,” he said, reaching in front of me and patting the door to the glove compartment. I opened it to find large wads of foreign banknotes—deutschmarks, pounds, and an especially fat roll of Italian lire. “I give you 12 roubles for dollar.”

I was spooked by all the cash in the glove compartment. What had happened, I wondered, to all his prior “customers”? Or did he even have “customers”—just victims? I passed on the deal. He drove up to the hotel entrance, where I parted ways with the guy—whoever he was.

The two people working the receptionist desk had no reservation for me and weren’t sure what to make of my payment voucher. After a lot of wrangling between the two behind the desk, one finally relented and checked me in. In my letter home, I described my accommodations. “I landed a posh room on the 11th floor. It was deluxe class by Western standards, but it was hardly Russian in flavor and not what I preferred. The [place] shook under the repetitive blast of disco music.”

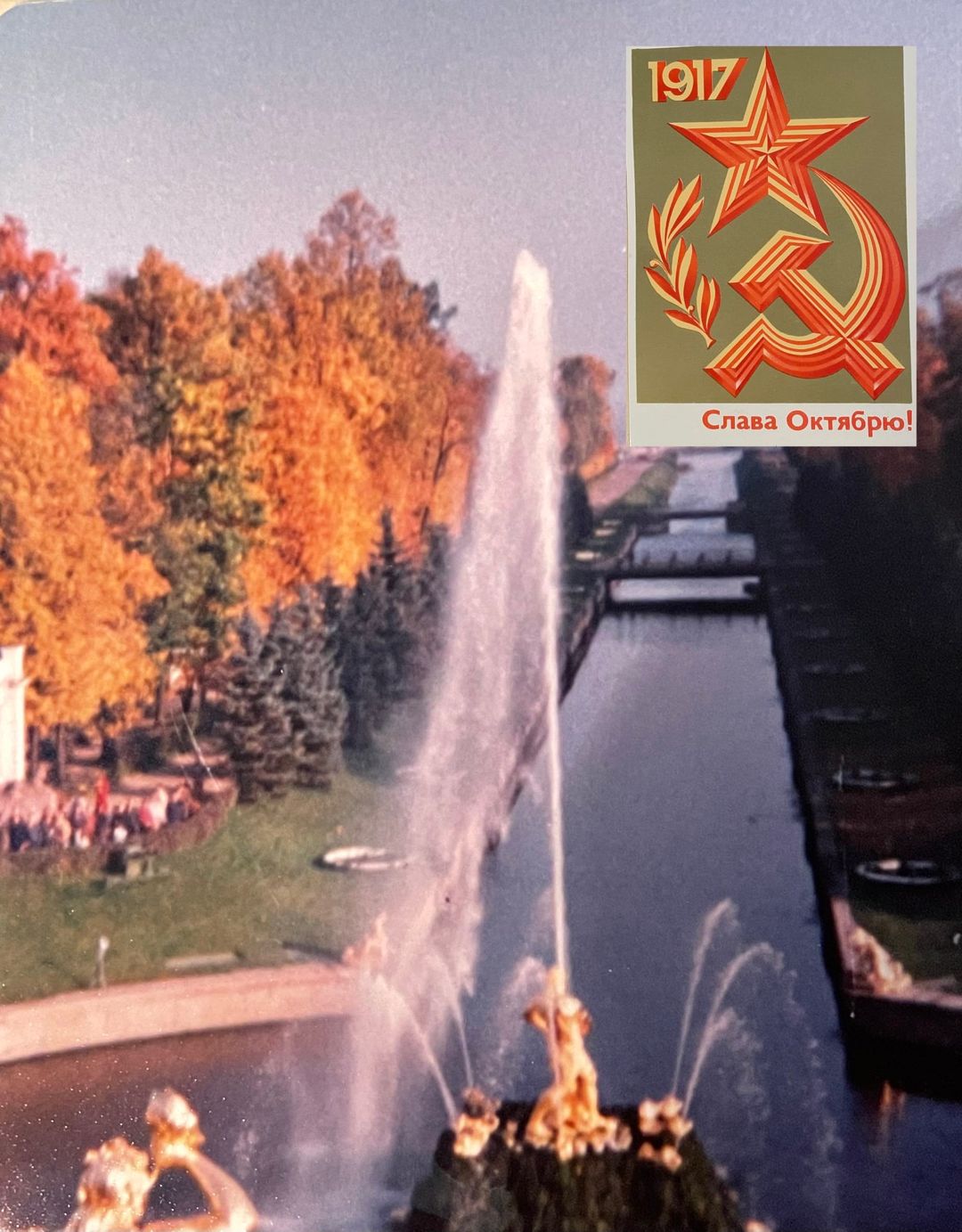

I spent minimal time at the hotel so that I could spend maximum time enjoying Leningrad—originally named Sankt Peiter Burch (Dutch) by Peter the Great, who’d lived in Holland for months to study Western ship-building. Later, to create a “window to the West,” Peter founded the city (on swampy ground) near the mouth of the Neva River; the spelling was subsequently Germanized to Sankt [Saint] Petersburg—until the outbreak of WW I, when all things German were vilified, and the name was changed to the Russian, Petrograd (“Peter’s City”), until the Bolshevik Revolution, when Petrograd became Leningrad. After the break-up of the Soviet Union, the city again became “Saint Petersburg.” (Cont.)

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson