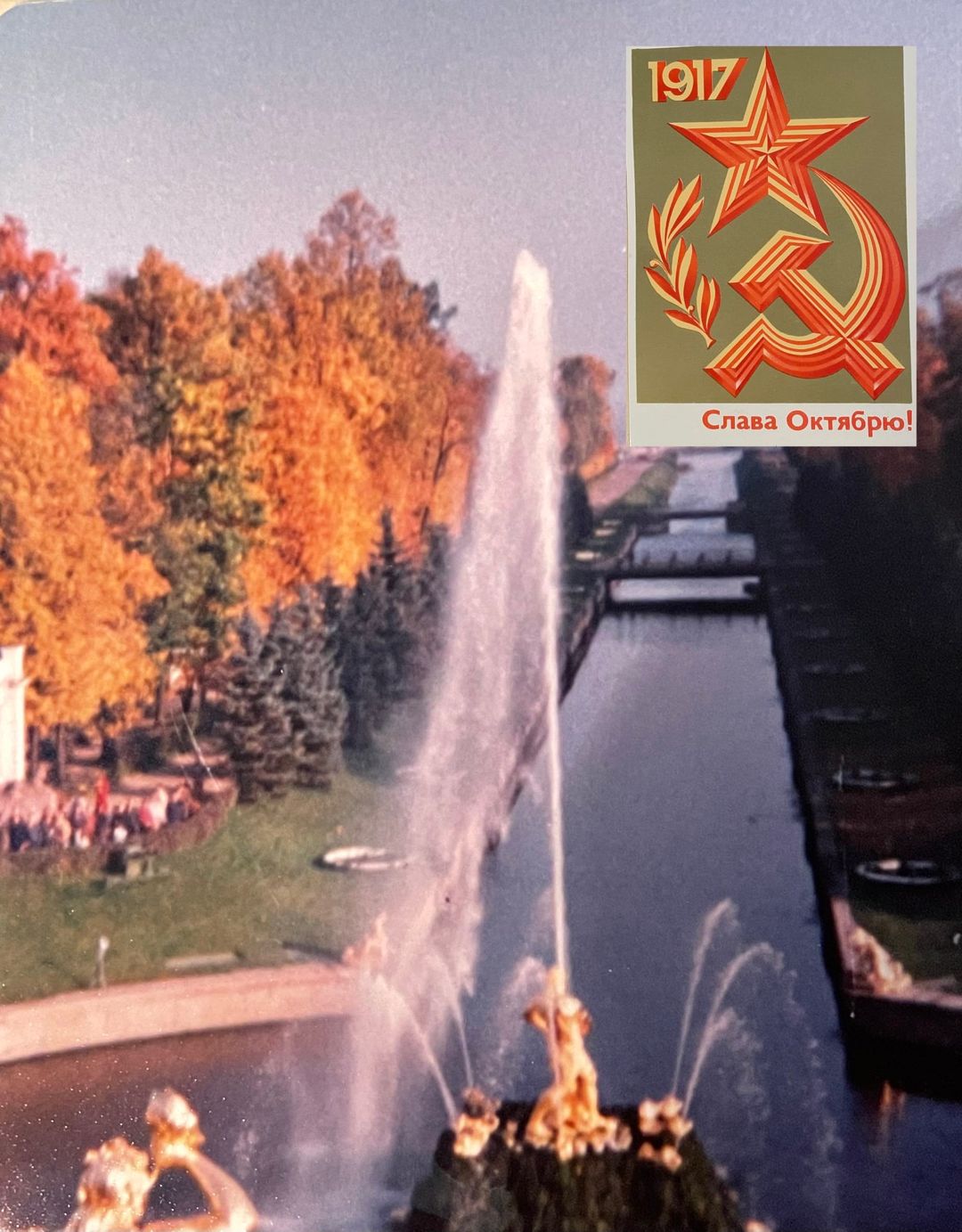

APRIL 25, 2022 – On its way eastward 111 miles to the Russian border, the Soviet train sped through birch forests ablaze with autumn color and past tranquil, mystical lakes. The scenery was reminiscent of music by Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. I thought particularly about Sibelius’s Karelia Suite, inspired by the troubled history of Karelia, the borderlands between Finland and Russia that Finland ceded to Stalin after the Winter War of 1939-40.

A fellow traveler in my compartment was a Norwegian, Johan-Bara, from Kirkenes at the far north end of Norway and ironically, a few kilometers from the Russian border, albeit 800 miles to the north of our train route. He was making his way to the Leningrad Conservatory, where he’d be studying with a pre-eminent maestro. A skier and hiker, the Norwegian was very attuned to nature, and our common interests in music and the great outdoors gave us plenty to talk about over the 10-hour trip to Leningrad.

The train arrived at the Finland Station* in Leningrad well after dark, and while other passengers scurried off into the night, I stood conspicuously on the platform. I’d been informed by the Soviet Consulate’s office in Stockholm that an Intourist (the Soviet travel agency) “guide” would be on hand at the arrival platform to meet me and drive me to my hotel. Which hotel, I hadn’t a clue, since all I possessed was a payment voucher. Long after everyone else had disappeared from the platform, I began to question the assumption—based on anecdotal information—that I was being watched or followed by the KGB.

With rising impatience, I wandered around the station and discovered a small Intourist office that appeared to be open for business. Upon entering, however, I wasn’t sure what kind of “business” was going on. Two guys were on duty, one seated behind a small, battered desk and the other tilted way back in a cheap chair next to the desk. Both wore black leather jackets. Both were blowing big plumes of cigarette smoke as I entered. The guy at the desk didn’t seem pleased by the interruption caused by my appearance.

“Do you speak English?” I asked.

“A little,” the desk man said as he stuck out his chin, shrugged his shoulders, then took a deep draw on his cigarette.

I showed him my payment voucher and explained what I’d been told at the consulate office in Stockholm. He was as unimpressed as he was uninformed. He looked at the voucher, turned it over, turned it face up, then handed it back as if it were an over-sized, counterfeit lottery ticket. The two guys talked—in Russian, of course—and in their tone and unhurried speech, I detected an utter lack of urgency. At the point when I was feeling invisible, the guy behind the desk leaned his head in the direction of his partner and said, “He will drive you.”

But drive me where?

We covered a disconcerting distance before turning down a dimly-lit side street. “Change money?” the driver asked. (Cont.)

________________________

*See To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History (1940) by Edmund Wilson, an account of Lenin’s return to Russia in 1917 via Finland from exile in Switzerland. As the name of the train station in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) suggests, the facility has long served as the eastern terminus of trains running between Finland and Russia.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson