MARCH 9, 2022 – Just as the Jewish person of faith in Jerusalem venerates the Foundation Stone; as a Muslim pilgrim in Mecca rounds the Kaaba; as a devout Catholic at the Vatican genuflects inside the Basilica . . . so does a classics/history major visiting Athens climb the Acropolis. I’d done so two years before (see yesterday’s post), but I was eager to clamber up it again, despite the blistering heat.

The Acropolis—Propylaea, Erechtheion, and Parthenon—had been a highlight of Professor Beam’s ancient art history course back at Bowdoin, and my return to the hallowed ground of Periclean Athens was a religious experience. In those days tourists were allowed within spitting distance of the base of the Parthenon—a guard’s shrill whistle scaring everyone from getting any closer; the heat ensuring that no one had anything left to spit. Like a pilgrim of sorts, I rounded slowly the Temple of Athena. I recalled the many architectural refinements of Ictinus and Callicrates, imagined the long-lost masterpiece of Phidias (the interior statue of Pallas Athena), and mourned the destruction of metope and pediment sculptures—losses by pilferage and warring sacrilege of Christians and Muslims alike.

Yet . . . despite its reduction to rubble, the Parthenon was of such refined design, I could look upon the wreckage and “see” what a wonder it’d been in concept and construction.

I spent several days in Athens, enjoying its past and present, but I was eager to escape the tourist scene and cross the Aegean Sea to a paradise worthy of a battle-weary Odysseus.

Before venturing over that fabled sea, however, I visited a small Intourist office—the Soviet travel agency—in central Athens. On the chance that the Red Army did not invade Poland in the coming months, I wanted to see Russia, as well as its nemesis, Poland. My subsequent trip across Mother Russia and back began when I happened upon that Intourist outpost in Athens.

My letter home described my encounter inside. “A 50-ish-year-old woman, built like a tank, [was in charge]. Initially, she seemed quite ‘correct’ and unaccommodating, but when I told her I’d heard her country was ‘very beautiful’ and that ‘my guidebooks say Moscow’s underground is the finest in the world,’ she warmed up. We chatted for a while, and after a few minutes, she was throwing all sorts of brochures and information my way. When I asked if there was a ‘tourist’ or second class rate as well as first class for rail travel and hotels, she said, ‘Oh yes, of course. You can go first class, second class or economy.’ She smiled, and I smiled back. I wanted to say, ‘I thought you were a classless society,’ but I thought it best to get in the habit of acting diplomatic toward Soviet and East Bloc officials.”

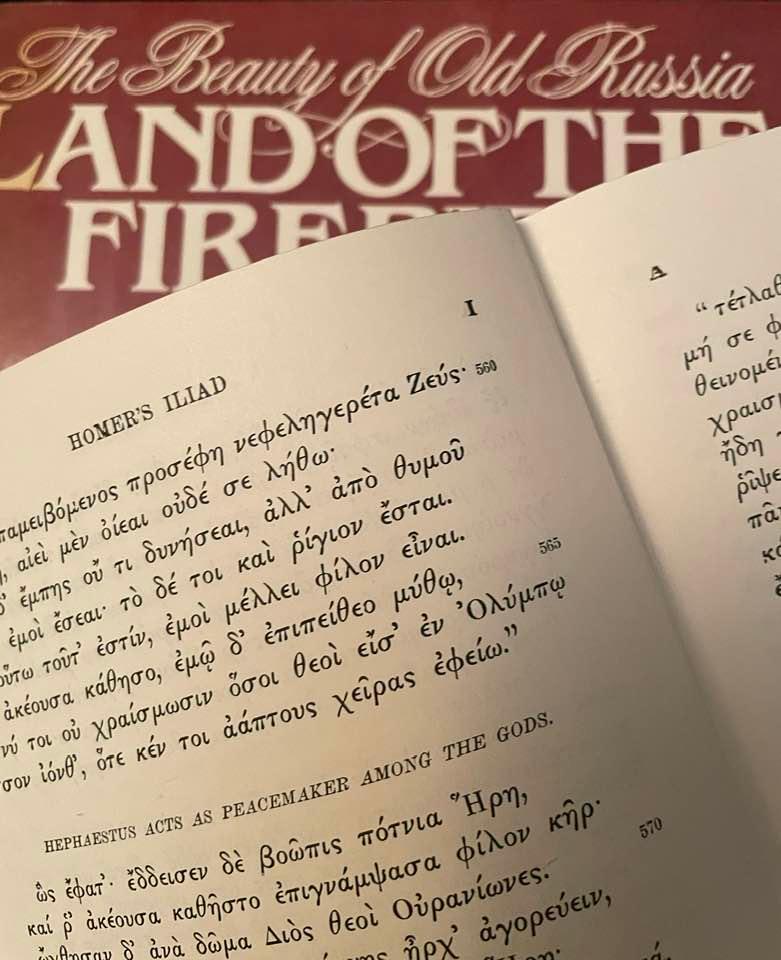

Back on the street, I was reading Greek—a cousin of Cyrillic. Early the next morning I was Odysseus aboard his ship in Piraeus, Athens’ port, casting off for the 14-hour voyage to Samos . . . home of Pythagoras.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson