MARCH 30, 2025 –

Yesterday evening we attended the opening night performance of Secret Warriors at the History Theater in downtown St. Paul. Despite the hard rain and temperature of 35F, a crowd just shy of the 587-seat capacity turned out for the production. Judging by the appearance of the attendees, I guessed that my age (70) brought the average age down slightly. What would attract older folks to the play? Perhaps it was the “history” part of “theater,” or maybe it was as much the subject matter—the Nisei (second generation Japanese-Americans) who attended MISLS (Military Intelligence Language School) at Camp Savage and later, Fort Snelling, both army bases in Minnesota during World War II—ancient history in the minds of many younger folks.

Only in recent years has America finally begun to acknowledge the gross injustice meted out to Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor and to honor the heroism of the Nisei in proving their patriotism. Minnesota’s special connection is rooted in the intense language school located here that prepared volunteer Nisei for deployment in the Pacific. Many were assigned to frontline positions where they could intercept and translate communications by Japanese soldiers and interrogate prisoners. The critical role these soldiers played was matched by the dangers—not only of combat but of being taken captive. Japanese captors would show the Nisei no mercy.

Before the play got underway, Richard Thompson, the enthusiastic artistic director of the theater, welcomed the crowd and reminded us of what truly makes “America great.” The audience demonstrated its agreement by frequent, hearty applause during his three-minute talk, which highlighted our core strength: people of the world coming together with new ideas and innovation. It was a positively-worded retort to fascism. Later, as intermission drew to a close, I espied Mr. Thompson just inside a doorway leading into the theater. He was talking with a patron, but I sneaked in from the side, excused myself, caught his attention and said, “You said exactly what needed to be said! Thanks much!” His face lit up as he returned my “thumbs up” gesture with his own.

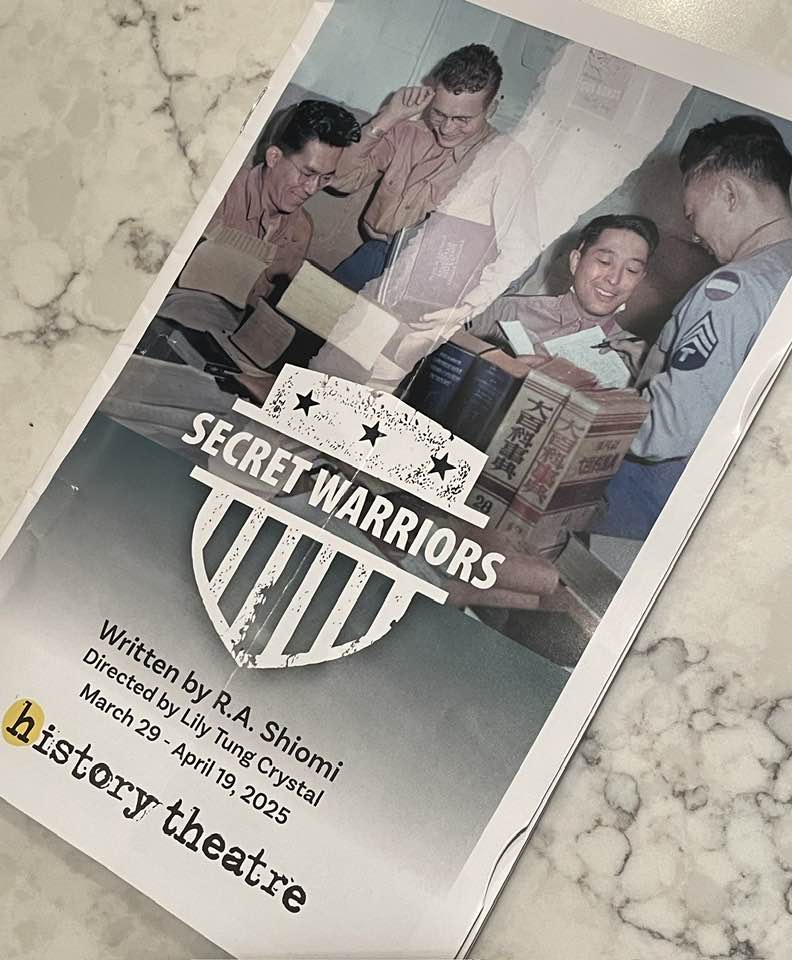

Written by R.A. Shiomi and directed by Lily Tung Crystal, Secret Warriors featured a cast of 10 included some playing double roles, one set in Act One (training and budding romances in Minnesota) and Act Two (fighting in the Pacific Theater). The central players portrayed actual characters and real events. By the end of the play, its components—script, acting, directing, and simple but effective set designs had nearly convinced me that the actors were the actual people they were portraying.

“Hmm,” I thought, as we followed the crowd shuffling up the aisle toward an exit. “I’d really like to tell Koji Kimura what a credit he was to our country, especially when he convinced the Japanese soldier his comrades had smoked out of a cave that surrendering was honorable, not shameful; and when Koji established a rapport with the haughty Japanese officer, Captain Isamu Iwata, who was initially disdainful of Koji—Iwata’s ‘ill-educated’ American-Japanese interrogator.

“And how about the American lieutenant, Jeff Nelson?” I said to myself. Nelson was in charge of discipline over the Nisei recruits in MISLS. To his credit, Nelson stood up to overt racism against his charges. After retiring from a long military career, in April 2000 he met up with Koji and another of the “Secret Warriors,” Masa Matsui, when the group was awarded a Presidential Citation for their remarkable contributions. (That it took over half a century for this to occur underscores the shameful treatment of Japanese-Americans during the war.)

Then there was the irrepressible Tamio Takahashi, son of grocers in a town outside of Seattle—model citizens who were treated like criminals; all their property confiscated and they themselves hauled off to an internment camp for the rest of the war; except Tamio volunteered to be a “Secret Warrior,” while one brother joined the all-American-Japanese 442nd Regiment that fought so heroically in Europe (he would die in combat), and another brother was among the “No-no” Japanese-Americans[1]. Tamio’s supreme acts of bravery combined with exceptional cleverness were effectively portrayed in the play. Sadly, though he’d been furloughed for a few weeks to visit his parents in an internment camp and his fiancée in Minnesota, he volunteered for the assault on Iwo Jima and was killed in action.[2]

How tragic—the scene where Tamio’s fiancée, Denise Murphy, a nursing student, was at the home of her good friend, Natsuko Nishi, from San Luis Obispo, CA (who eventually married the mild-mannered Koji, son of a farm family just outside of San Luis Obispo) and English major at Macalester College in St. Paul—both waiting for their Koji and Tamio to arrive on furlough—except, only Koji appeared . . . late . . . and bearing the awful news that his friend and Denise’s love had been killed.

It was enough to wrench one’s heart right out from behind its rib cage.

As we stepped out into the cold pouring rain, I recalled the story of “Above and Beyond” in my post of March 15: “War brings out the very worst in bad people and the very best in good people.” Secret Warriors did a superb job of portraying and re-enforcing that adage. If you’re within range of St. Paul, see it. You’ll be glad you did.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

[1] These were the young Japanese-American men who answered “No” to questions 27 or 28 (or to both, which was the usual case) on the government’s loyalty questionnaire that all interned Japanese-Americans were required to complete. The two questions were: (27) “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” and (28) “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces?” Many of the “No-no” respondents went on to distinguish themselves as civil libertarians.

[2] Supposedly, American control of Iwo Jima was deemed a necessity for support of B-29 bombing missions over the main islands of Japan. Army brass concluded that given logistical constraints, Iwo Jima would serve as an essential intermediate base. The Japanese operated under the converse logic. As matters developed, however, alternative airfields were used. The island turned out to be of no special strategic value to the Americans, and therefore, its defense was not a strategic imperative of the Japanese. Yet casualties on both sides were staggering.