DECEMBER 10, 2023 – Nearly always a huge gap separates someone’s bizarre dream from the person’s description of it. Inevitably, the bright, colorful details of a dream fade quickly, though the general impression holds firm, at least through the dreamer’s transition into consciousness.

“Oh my gosh but I had the weirdest dream last night!” your houseguest says over the first cup of freshly brewed coffee.

“What?” you ask—mostly out of politeness, not curiosity, since you’ve been down this road many times, and chances are that what you’re about to hear won’t match the travel brochure.

“I was in this strange building,” the houseguest starts in, “whom I haven’t seen in years, came in with a six-pack of beer in one hand and a garden rake in the other and asked me if I’d be up for a game of gin rummy. And then I was sitting at a table at work with three open boxes of stale donuts, and my boss said ‘Help yourself,’ but I didn’t want one so I said, ‘No thanks,’ and the next thing I knew I was in the bow of a canoe with the handle of a broken canoe paddle . . . and then . . .”

“Cream and sugar?” you interject.

“Uh, just sugar, thanks.”

“Okay, here you go . . . oops! [you lift the lid to check if there’s any left, since you yourself never use sugar] . . . I’ll have to refill . . . do you prefer refined sugar or brown sugar?”

“Brown would be great, actually.”

“I’m on it. I used to put sugar in my tea, but for the last 10 years I’ve used Ovaltine. Have you ever tried Ovaltine?”

“No. What’s Ovaltime?”

“Lower sugar chocolate—according the label, anyway. Do you like chocolate?”

“Sometimes—especially dark chocolate.”

By then the conversation has veered successfully off course, and the dream—and its inadequate description—fade away altogether, even though your guest was just getting started.

I myself am a big-time dreamer. Every single night I experience a multi-feature film fest in a cranial theatre equipped with SurroundSound and a super-sized color-enhancing screen. I see and hear enough stuff to pin down any and all house guests from the first cup of morning coffee to the third round of late afternoon alcoholic beverages. However . . . out of courtesy I’ve learned to curb my enthusiasm. Besides, half the time a detailed account of my dreams would result in issuance of a warrant for my detention before I say anything that might interrupt the earth’s rotation.

Exceptions occur, of course, and Friday night’s quadruple-feature included one.

The scene was the White House, circa 1867—Abraham Lincoln’s second term. The incident at Ford’s Theater two years prior had turned out to be an unsuccessful assassination attempt. The 16th president was alive and kicking—well, actually, not kicking: his long right leg was fully extended and awkwardly as he occupied a straight-back chair in the Oval Office, for the limb was wrapped from toe to thigh in a hard plaster cast. I was nearly euphoric to learn that the pistol of John Wilkes Booth had misfired, singeing the would-be assassin’s hand but leaving Lincoln unharmed. My relief and delight, however, were tempered by the fact that as an improbable visitor I had negligently caused the gangly Commander in Chief to stumble within that very room, resulting in compound fractures of his femur, fibia, and tibia—the downside of his commanding height.

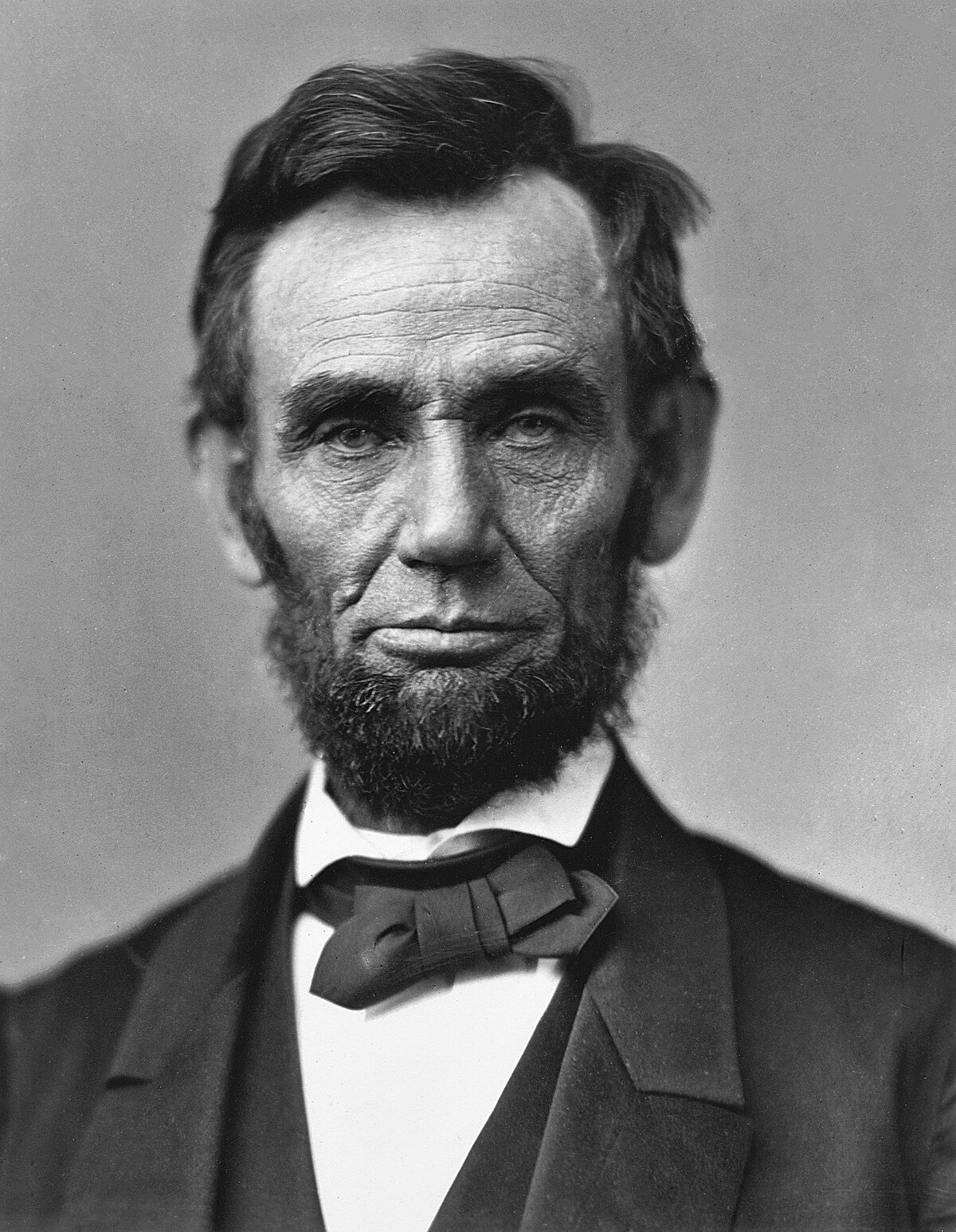

Beyond this mishap, three things struck me about Lincoln. First, he matched perfectly his photographic images; though only 58 years old, his elongated physique—even seated—and unruly hair made him look older than I, a dozen years his senior.[1] Second, he was a most amiable and conversational character. He treated me kindly as if I were a familiar and well-liked acquaintance, even though this was our first encounter. Third, he exuded intelligence. Simply in the way he spoke, he conveyed his intellectual alertness. It’s hard to describe the basis for this, since he spoke only about the broken leg and how he was trying to adjust to his present confinement to the chair, but his word choice and delivery communicated a big brain fully engaged. Of course, my impression was enahanced by his reputation as a gentleman and a scholar, not to mention a shrewd, high-powered courtroom lawyer.

I apologized profusely for having caused his injuries. In response he dismissed my negligence, insisting his stumble and toppling were “purely an accident” and that I should feel no pangs of guilt whatsoever. This went a long way—six feet, five inches, to be exact, which coincided with the length of his frame—to relieving my stress, but I still held regret, which I proceeded to express.

“Thank you for your graciousness, Mr. President,” I said, “but I deeply regret that in having been afforded this highly unusual audience with you, the topic of conversation has been limited to your unfortunate physical condition for which I’m directly responsible—negligent or not. I mean, of all the subjects that your great mind could address—from literature to religion to political science to the causes and execution of the Civil War, for crying out loud, not to mention your advice and insights into the condition of the country as the world now finds it—I’m sorely disappointed that because of my clumsiness, I caused you undue harm and jettisoned the certain rewards of hearing your discourse on numerous topics of mutual interest.”

Lincoln chuckled with reserve. “You overestimate my capacity for such,” he said. “I’ve had to meet the challenges that have confronted me and I’ve done so in the best way I know. I’m no hero, no better man than any good man, and that’s a fact.”

His statement was evidence of the paradox associated with all “better people”: humility precludes the self-perception that they’re “better than good.”

What followed was the typical transition from one “feature” dream to another, much like the shift to the “Ghost of Christmas Present” from the visit of the “Ghost of Christmas Past” in the timeless masterpiece of Charles Dickens.

When I awoke several dream sequences later, I mulled over my encounter with Abe Lincoln. What could’ve prompted the dream? I couldn’t recall having thought of him—directly or subliminally, for example, by having handled a five-dollar bill—in quite some time . . . Except . . .

. . . Two nights previously I’d been reading Paris 1919, Margaret Macmillan’s prize-winning account of the Paris Peace Conference following the end of The Great War (WWI) dubbed hopefully at the time as “The War to End all Wars.” In the early pages of the book, Macmillan introduces Woodrow Wilson, a man as flawed as any other, but also, as with most of us, not altogether lacking redeeming features. Among his positive attributes was an admiration for Lincoln, a striking feature given that Wilson was a Southerner—or more specifically, a loyal Virginian.

Aha! I thought, as I recalled the Wilson-Lincoln connection in Paris 1919. Doubtless that had been the trigger for the Lincoln dream. Apart from the title role, however, I could find no other connections other than my general concern about the current state of affairs afflicting our body politic.

In any event, I can now add Honest Abe to the list of world figures—mostly despicable— who’ve appeared in my dreams: Enver Hoxa, the Stalinist dictator of Albania (setting: a small convenience store in Tirana); Kim Il Sung, the self-deified dictator of North Korea (setting: a reception area at the DMZ); Fidel Castro, the Communist dictator of Cuba (setting: a taxi cab in Dallas (of all places)); and get this—Adolf Hitler the . . . uh, well, er, Hitlerian . . . dictator of Nazi Germany (setting: an outdoor viewing stand in Berlin). For years I was troubled by the bad guy appearances in my dreams. Now, finally, one of the good guys showed up.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] As is the case with all my elders in life, in my recollection of them, their original seniority to me remains. My grandparents, for example, are always be “old people” in my mind, even when I think of them when they were much younger than I am now. Same with historical figures to whom I was introduced when I was a school boy. Lincoln, who died at 56, and Washington, at 67, will always be “much older” than I am—at 69 and beyond.