APRIL 6, 2025 – Blogger’s note: When I sat down to write this series, it didn’t start where I’d planned—nor will it end where I’d expected. Part analogous, part allegorical, part anticipatory, the story is as much about the present and future as it is about the past. But then again, as we’re reminded continually, these three dimensions of time are inextricably linked. I hope the reader will find the series amusingly and profitably thought provoking one way or another, especially against the backdrop of our current national politics.

A half century ago I launched my short-lived political career in elective politics. It was highly successful as far as it went, which was exactly one term—to the end of the following school year. My last official act was as class marshal leading my classmates down the long aisle of the temporary stage of our commencement exercises on the campus quadrangle[1]. As photographs reflect, the weather gods smiled on us that day, thanks no doubt to the entreaties and burnt offerings of the ever so popular professors of the Classics Department, the endearingly mocking Nate Dane, the wryly jocular John Ambrose, and my namesake—in spoken form, anyway—the cheerful yet serious Assistant Professor Erik Nielsen, who stood in the inevitable shadows cast by the living legends, Dane and Ambrose.

My political career, as it were, started rather haphazardly. I was sitting alone in an alcove of the dining room, wolfing down my supper. It was a Sunday, and for reasons I can’t remember today, exactly a half century later, I’d missed joining my usual meal-mates and reached the cafeteria line just before closing. Most students had already consumed their Sunday roast (beef or poultry; we ate well, in any event) and repaired to room desks or library carrels for the predominant Sunday evening activity: hardcore studying for the week ahead.

At some point between mopping up gravy with a dinner roll or digging into my bowl of ice-cream, Jeff Oppenheim, my good friend and roommate (of three), swooped into the alcove and helped himself to a chair.

“Eric,” he said breathlessly. “We have a serious problem on our hands.”

“Huh? Let me guess. A chair or an indoor fastball inadvertently crashed through the main picture window and injured someone on the ground below.”

“No, nothing like that,” said Jeff impatiently. “PJ has decided to run for class president. Worse yet, he’s actually campaigning for it. He’s already put up signs. They’re kinda clever, actually. His slogan is, ‘Prune Juice makes things move.’”

The classmate Jeff referred to was one Patrick J. McManus, a wily guy from Lynn, Massachusetts, who went by “PJ,” which stood for “Prune Juice” as much as for his real name. He was brash and witty and fashioned himself as NFL material, though if there’d been a sliver of realism to it, PJ wouldn’t have chosen to attend a small liberal arts college in Maine, where football took a backseat to soccer, hockey and lacrosse—not to mention Nate Dane’s popular early morning survey course on Greek and Roman Mythology, dubbed “Gods for Jocks,” since there were no prerequisites.

In any event, as I was to learn PJ had his political career all mapped out: after gaining fame as an NFL star, he’d run for mayor of his hometown; after a term, he’d scale up to Congress; two or at most three terms later, he’d run for the Senate. “And who knows, after that,” PJ would tell me with mischief in his eye as he alluded to the highest office in the land.

On the one hand, PJ’s extravagant ambitions didn’t match his aptitude—at least in the narrow perspective of people on campus who know him. He wasn’t exactly a scholar. A smart aleck, sure, but a serious student of say, political science (or “government,” as it was called out our school), as so many of our classmates were? No way. Moreover, his general behavior was that of a witty clown. Friends and acquaintances laughed at his antics but no one took him seriously, and it seemed that no one took him less seriously than he himself.

On the other hand, and very much in retrospect, PJ had the skill set that could serve him well in the rough and tumble world of elective politics. He was thick skinned, and he could take as much sarcastic punishment as he could dish out. Also, behind all his balderdash was a single-minded determination to “run the ball” all the way into the political end zone. The only flaw in his overall plan was a serious knee injury, which, among other considerations, severely limited the prospects of NFL stardom.

But meanwhile, I had my own political ambitions (later tied to an hallucinogenic athletic fantasy as improbable as PJ’s—namely, in my case, recognition as an Olympic class skier). Jeff, who shared my keen interest in politics, if not my ambition to run for elective office, was well aware of these ambitions.

“Eric, we can’t let that happen. We can’t let the PJ the class clown become class president.”

Jeff knew PJ far better than I; they’d worked together one summer at a YMCA camp, and Jeff, always Mr. Responsibility, whose middle name was and still is “Conscientious,” was disapproving of PJ’s brash approach to everything—though Jeff didn’t deny that PJ’s obnoxious behavior is exactly what people subconsciously found charismatic about him.

I knew PJ well enough to share Jeff’s impressions of PJ, though not at the same level of concern. After all, who cared one nit about who was class president? It was a position of absolutely no importance or even visibility. I had no idea, for example, who held the post for the class ahead of us, and I knew most of the members of that class (our college had a total student body of only around 1,250). During our first two years at the college, I’d been wholly unaware of an election, let along any kind of campaign, of a senior class president. As far as I knew—and indeed, as far as Jeff knew—the “job” as it were, was nothing more than a title. It conferred an honor without the bother of any responsibility. Ever since our matriculation in the fall of 1972, our campus was conspicuously non-political. I’d never heard of any student voting for any position, let alone running for one.

When I pointed out this background to Jeff and challenged him over his concern, he pushed right back. “Yes,” he said, “but with his campaign signs, PJ has changed the rules. Suddenly, senior class president is going to mean something to people. Fine, but if we do nothing it’s going to be PJ, for crying out loud, who will then fill the position that he will make into something merely by campaigning for it. We can’t allow it!”

Then Jeff lit the match: “You should run against him,” he said.

“Huh,” I grunted. If at one level I was persuaded by Jeff’s logic, his concern kindled both my amusement and my ambition. “It could be kinda fun, actually, to run against him; beat him at his own game.”

“Exactly. So, are you in?”

“I think so,” I said, “but before we get too far ahead of ourselves, what are the actual responsibilities of the class president?”

“I’m not sure,” said Jeff. “I think it’s more a social position. I mean, I think that more or less you’d be social chairman of the class; you know organize parties, that sort of thing. There are probably some other responsibilities, but I think they’re pretty light. The point is, we can’t allow Pat McManus to hold this position. We’d be making fun of ourselves if we allowed that to happen.”[2]

“Yes, if you’ll serve as my campaign manager.”

“Sure,” said Jeff.

We’d been good friends ever since meeting freshman year in the first hour class we shared, “Survey of Western Civilization” team-taught by Roger Howell, president of the college, whose academic specialty was English history, and Paul Nyhus, the college Dean of Students, a medievalist. Only about 10 students had signed up for the course, so on the day of the week that was reserved for “discussion,” we were rather exposed. I’ll never forget the moments at the beginning of those sessions—President Howell lighting his pipe as we watched in silence and anticipated the challenging questions he’d pose and that we’d attempt to answer. Jeff always made a good impression when he spoke while Howell puffed.

Whether applying himself to his studies or arranging outing club trips, Jeff was always well organized. He’d proved himself brilliantly as co-founder and co-leader of our on-campus terrorist group earlier in the semester, the Bowdoin Pie Throwers Organization or “BPTO,” for short. Plus, Jeff had spent the previous (fall) semester on an exchange program at American University in Washington, D.C., where he also worked as a part-time intern in the office of Rhode Island (Jeff’s home state) Senator Claiborne Pell. If anyone on campus could run an effective political campaign, it would be my good friend Jeff “Conscientious” Oppenheim.

We went straight to work and spent the next couple of hours plotting the campaign to elect AMERICA Nilsson as President of the Class of ’76. Of course, each of us had plenty of studying on our dockets that evening, but first things first: we owed our class a duty not to allow PJ to run unopposed, when duty rings, every good citizen answers the call. That maxim was as true then as it should be today. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2025 by Eric Nilsson

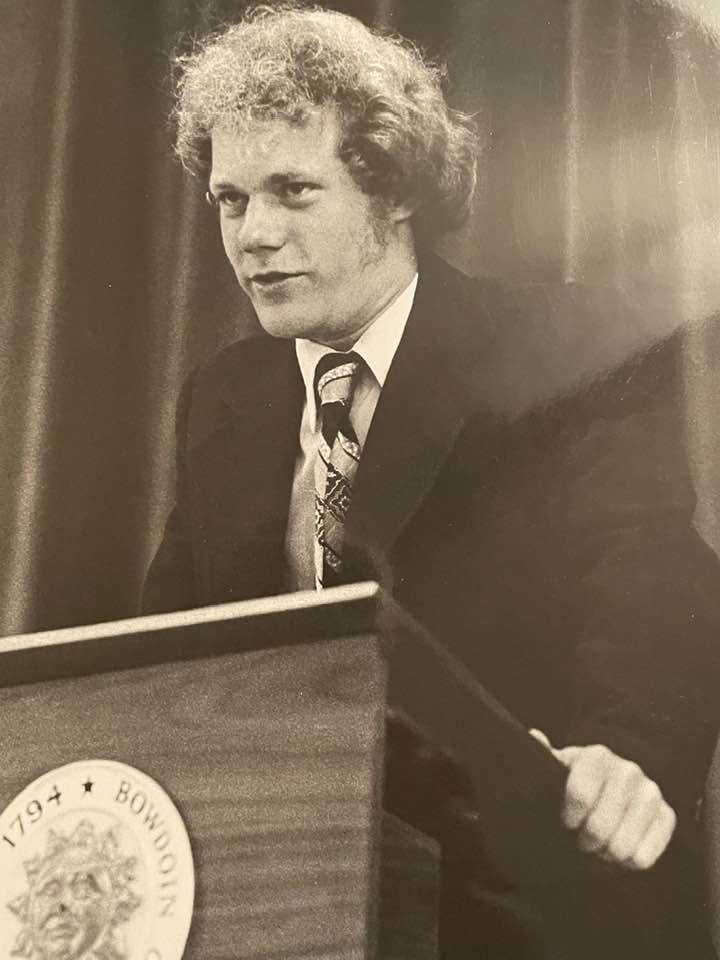

[2] In due course I’d learn that there were in fact three additional duties. As mentioned above, one was to serve as class marshal at graduation, and the second was to attend monthly meetings (as the student member) of a committee established to make certain recommendations to the administration. Fifty years later, I can’t tell you the name of the committee or what our particular mandate was. All I remember is that a member of the math department, the dean of students (Nyhus), another administrator, and an assistant also attended these meetings. What I learned from them was that organization meetings have three parts: 1. An agenda; 2. Lots of talk; and 3. Adjournment. I didn’t know it at the time, but this was an apt lesson for my future career. My third duty was sprung on me in the middle of lunch at an alumni gathering the day before graduation. Just as I stuffed some iceberg lettuce from my sale into my mouth, the college development officer who’d been wandering about stopped next to my seat and asked if I’d “give a little speech” to the crowd during dessert. I nearly choked. I’d been invited to the lunch, but no one had told me anything about having to “give a little speech.” I chomped the lettuce down to size and swallowed hard. On the back of a program, I scratched out “a little speech” (see below) and at the appointed time, managed to deliver it without embarrassing myself—or the class—too much. (See featured image.)