APRIL 10, 2022 – In Poznan I found a cheap hotel near the university. I seemed to be the only customer. The threadbare lobby, creaky elevator, and stick furniture in my room looked untouched since 1950. A hard rain discouraged exploration of the town, and since I hadn’t slept aboard the overnight ferry from Sweden, I took a nap—while scratchy recordings of classical music played from the only station on the old-fashioned radio.

When I woke an hour later, the rain had ended, so I left my room and stopped at the reception desk for walking directions. The young woman on duty, Katarzyna, spoke little English but fluent French. Butchering it quite well, I managed a conversation, which I later mentioned in a letter home:

“[Like so many Poles] I met, she was so friendly, gracious, and good-natured. When her boss (an exception to ‘good-natured’), a woman about 50 years old, scolded her for talking to me so long, I gave Katarzyna some extra chewing gum [unavailable in Poland], consulted my French lexicon, and told her, ‘Pour votre patron grincheux’ [“For your grouchy boss.] Katarzyna laughed and said, ‘Parfait!’”

Her cheerfulness was typical among the Poles I met. However difficult daily life had become—severe shortages of everything from bread to toilet paper (two small pieces of shredded newsprint—for which there was a charge—in public lavatories) were chronic—Poles had sipped from the well of freedom, and there was no going back.

* * *

At a coffee shop in Poznan I discovered a phenomenon unique to Poland: at eating establishments, you didn’t wait for an empty table; you watched for an empty chair—a jackpot for meeting people.

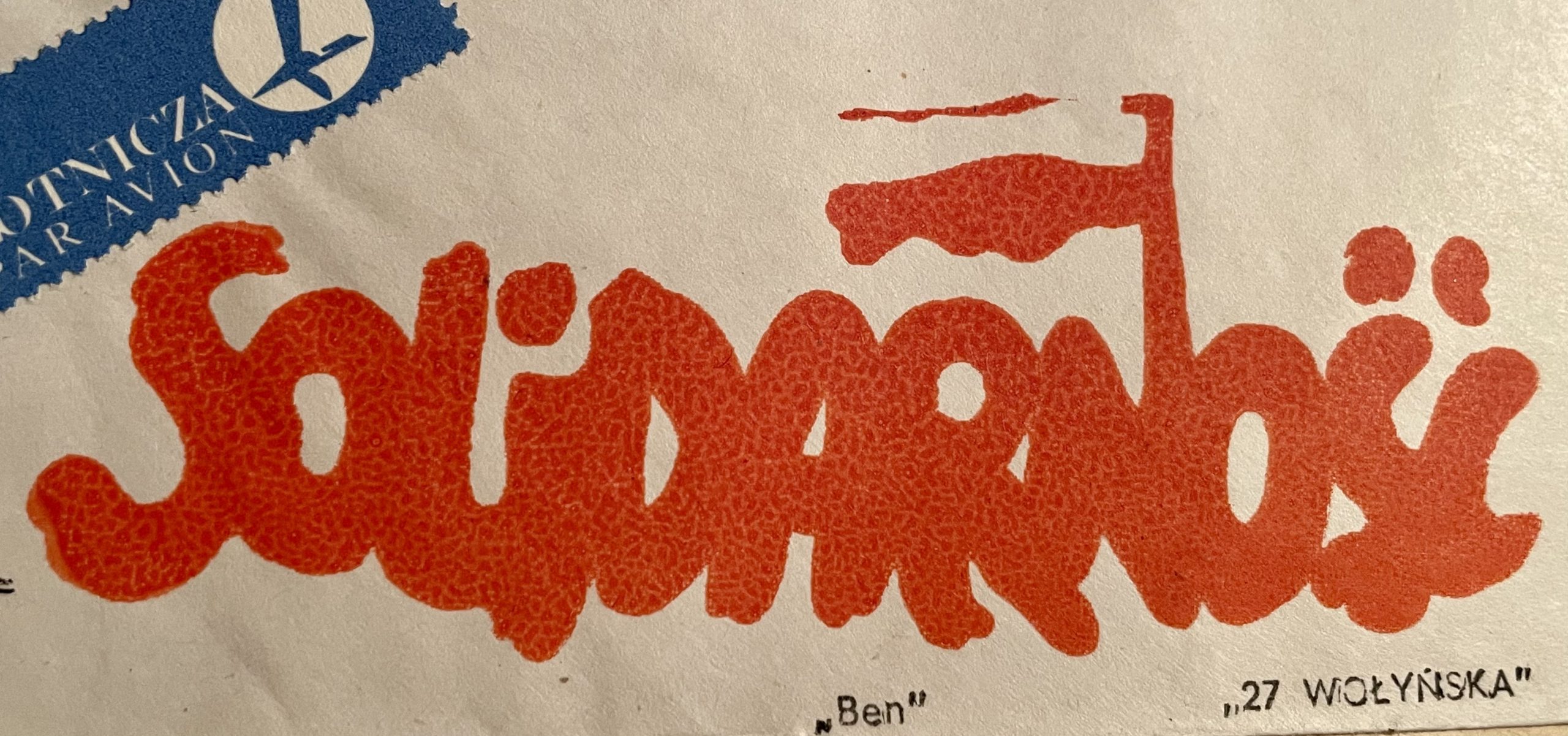

Often, a person at the table spoke at least a smattering of English or French and was eager to practice. (Russian was compulsory in school, but no one wished to speak it.) After introducing myself, Poles were thrilled to “tell their stories” to a Westerner. In most cases the first assumption was that I was British, since even the paucity of British tourists contrasted with the absence of American travelers; when I identified myself as “amerykański,” Poles thought they’d hit the jackpot—“Reagan, dobry!” (Reagan, good!), they’d say. As each patron left to catch a train or keep an appointment, another Pole would join the table. After catching on to this practice, I hung out in busy cafes long enough each time to meet and talk in earnest with a dozen or more Poles at the same, small table. This efficient process afforded a compelling view into the defiance that had gripped the country in the year following the famous Gdansk shipyard strikes and formation of the Solidarity union.

In the Poznan coffee shop, I took a seat at a table occupied by Włodzimierz, an engineer. He spoke English and was eager to educate me about planned political demonstrations all over the country. In my notebook* he jotted down dates and places where large street gatherings in support of Solidarity would occur. He encouraged me to visit Solidarity headquarters in Warsaw and gave me the address. He also urged me to witness the first annual Solidarity convention planned for Gdansk at the end of the month.

Włodzimierz’s “itinerary” proved to be an accurate road map into Poland’s Solidarity Revolution.

_______________________

*In retrospect, this seems a bit risky. If I’d been apprehended by the police and the notebook found, the authorities would have valuable intel. A few days later, however, I saw notices posted by the police (and translated enthusiastically by passing Poles) calling for the formation of their own union within the Solidarity movement!

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson