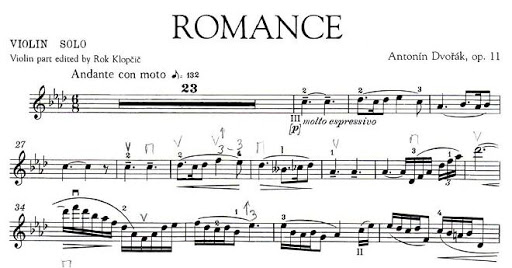

DECEMBER 21, 2020 – I’m currently studying a piece (Anton Dvořák’s Romance for Violin) with the marking molto espressivo (Italian for, “very expressive”) at the violin’s initial entrance. I’ve always been amused by such a marking, for it implies that only when you’re told explicitly should you be . . . expressive. But isn’t all music alwyas to be performed with expression?

But what is “expression,” let alone “lots of it”? Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians (ancient edition), the last word on musical terminology, punts. It defines “Expression” as “That part of music which may be called the ‘soul’ of the performance. It is hard to define exactly wherein it lies, but it is easy to recognize its presence or absence.”

Oh good. That tells me exactly what to do with Dvorak’s Romance.

But during yesterday’s practice session, I took a really hard look at the opening phrases of this beautiful, familiar piece by the late 19th century Czech composer and for a time, director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York. Without first consulting Grove’s—or any other source—I started with a notion no more definitive than “soulful, with a large dose of sweetness.”

What next?

Here’s where I experimented with the opening phrase, many times over. Each time I applied a host of effects, which, as in any artistic or athletic endeavor, come subconsciously but develop into a refined whole only by repeated conscious effort.

First was the bow arm and grip. Lots of stuff happening there: bow pressure, bow speed; angle of the grip; section of the bow; and, of course, bowings (upbow, downbow, slurred, tied, elongated, staccato). Second was the left hand—fingering the notes. Again, lots to consider: placement for intonation; vibrato (speed, width); fingerings and shifts. Superimposed over the bow arm and left hand was the structure of the music, as dictated by notation—time and key signatures; note values (rhythm); tempo and dynamics; eventually, coordination with the accompaniment, piano or orchestra.

All of these elements were fed into a figurative blender powered by heart and brain, between which lay no clear demarcation. The resulting sound smoothie, tasted like something that an audience would recognize as molto espressivo.

By experimentation I developed a deeper appreciation for a piece with which I’d long been familiar—as an audience member, never before as a performer.

The process was wonderfully satisfying as I forged a new relationship with the piece, as I dovetailed musical notation and markings with my interpretation of their possibilities. For the precious time of my practice session, I felt as if I’d entered a vibrant art studio; a place where heart, mind, soul, and the physical elements of violin-playing collaborated to cast something interesting on an aural canvas.

I also discovered that an old dog can teach itself new tricks—or at least convince itself of such (not sure about the “dog” part). In any event, it was all worth the price of admission.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2020 by Eric Nilsson