MARCH 7, 2023 – My mother was heavily involved with her branch of Christianity—the Episcopal Church. Over decades, she was church organist, youth choir director, Sunday school teacher, vestry member, Bible study leader, building committee member, chief informal advisor to the rector, head of this committee and that . . . not to mention a significant contributor to the collection plate. Much of her social life also revolved around church. Despite Mother’s zealous example, however, only one of her four kids is a fervent Episcopalian. Two of us don’t even belong to a church of any brand.

I’m not against church or Christianity or religion. In fact, I was once as heavily engaged as Mother was, though my brand was Lutheran—E.L.C.A., never to be confused with the ultra-conservative Missouri Synod or the ultra-ultra-conservative Wisconsin Synod. For a story’s worth of reasons, I strayed from the flock.

Nevertheless, I remain interested in the culture, history and psychology of religion, and though I’m alternately baffled and repelled by the dogma of faith, I embrace the cultural and humanitarian aspects of every mainstream religion. Besides, there’s something comforting about religious ritual, as long as it doesn’t involve abusing children, burning heretics at the stake or drinking Kool-Aid (wine is fine).

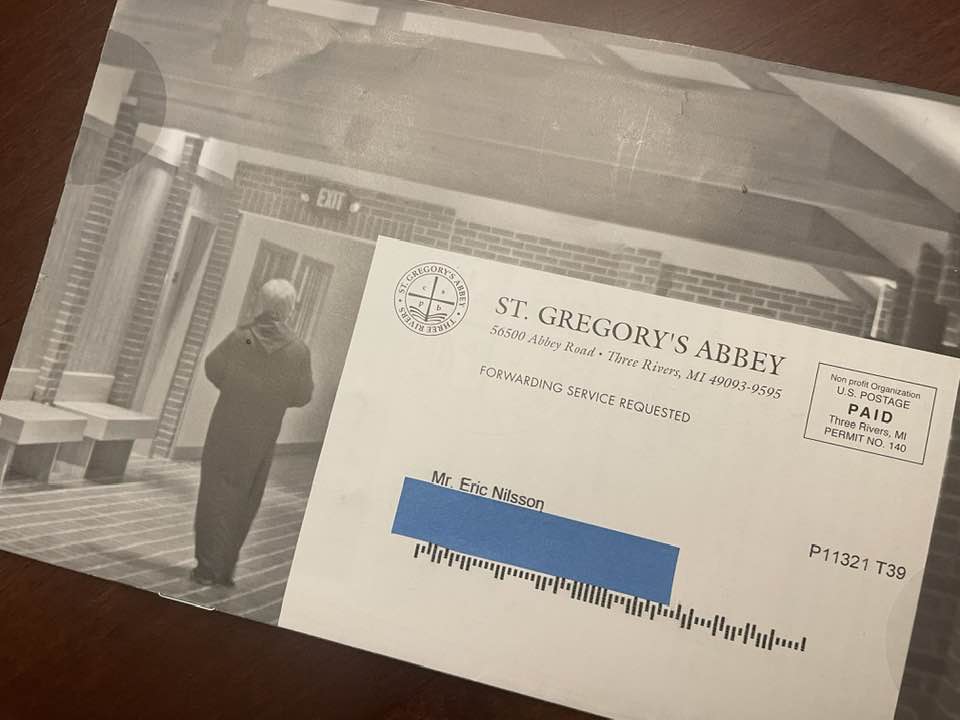

Despite my detachment from organized faith generally and the Episcopal church specifically, I remain on the mailing list of St. Gregory’s Episcopal Abbey in Three Rivers, Michigan. Every quarter I receive the order’s thin publication. It’s the last vestige of my mother’s connection to the Episcopal Church and thus, my own, reaching back over 40 years ago, when she submitted my name for inclusion on the Abbey’s mailing list.

At first I ignored the mailings, but when coincidentally I hatched the idea for a novel featuring a rebellious character who, in penance for all of his misdeeds, joined a monastery, I started paying closer attention to the St. Gregory publications. For a time, to conduct research for the novel, I considered taking advantage of St. Gregory’s two-week visiting program mentioned in each publication. An age limit of 50 ultimately extinguished the idea. The novel has since faded from my ambitions, but I still faithfully read the publications, more out of bemused curiosity than anything else.

Each publication describes the Abby as . . .

[T]he home of a community of men living under the Rule of Saint Benedict within the Episcopal Church, where God is worshiped in the daily round of Eucharist, Divine Office and private prayer. Also offered to God are the monks’ daily manual work, study and correspondence, ministry to guests and occasional outside engagements.

The monastic existence has its appeal, as I can attest from my week-long periods of seclusion at the Red Cabin, which stays allow for ample contemplation but no prayer sessions—unless you count “Star light, star bright, upon you I wish tonight [my wishes, followed by a proper “Amen”],” which I recite religiously every night there’s no cloud cover. In addition, pandemic isolation followed by my immune-compromised-bubble life over the past year-plus have in many respects mimicked a monastic existence.

But apart from my religious detachment, I’m too much a people person, too desirous of being engaged with the world to be a monk. I mean, a person is allotted precious little time to experience life on planet earth, and to dedicate one’s limited ration to a life of isolated prayer in the company of others committed to such an earthly fate would in short course feel as much as a life in prison as a life given over to one’s god or God.

The black and white photos of a monk pitching hay on the monastery’s farm, another monk leading matins (at the unholy hour of 4:00 a.m.) or all the monks sipping soup and buttering their bread in their newly constructed dining hall lose their allure in the light of time unending . . . until you croak.

The publication has provided just enough information to render me grateful that I’ve thus far avoided both prison and the life of a monk. How could any sane person, I’ve wondered, desire near continuous isolation from the insanity of the world—except through the lens of TV and the internet (the monks have access to both)?

But then yesterday’s edition arrived. The main feature—always a letter by one of the monks—threw me for a loop. (Cont.)

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson