JUNE 5, 2024 – Back in the day when I was a compulsive runner and x-c skier, I didn’t think much during the thousands of hours I spent pounding the pavement or striding relentlessly down the track. The physical demands were too intense to allow for anything but focus on pace or . . . metaphorical imagery to support endurance. Anything besides basic arithmetic (e.g. time elapsed divided by mileage times 26 (no “point two”) to simulate a marathon pace) was too much of a diversion.

“Metaphorical imagery” amounted to conjuring up a complex, imaginary feat of endurance that could hold my attention for a couple of hours. The key was to devise a scenario that was a far greater test than the one in which I was then facing voluntarily. My strategy was to lock into a well-practiced pace early on in the race, then shift into autopilot. For the rest of the long-haul, I’d busy my thoughts with the detailed construct of the metaphorical challenge.

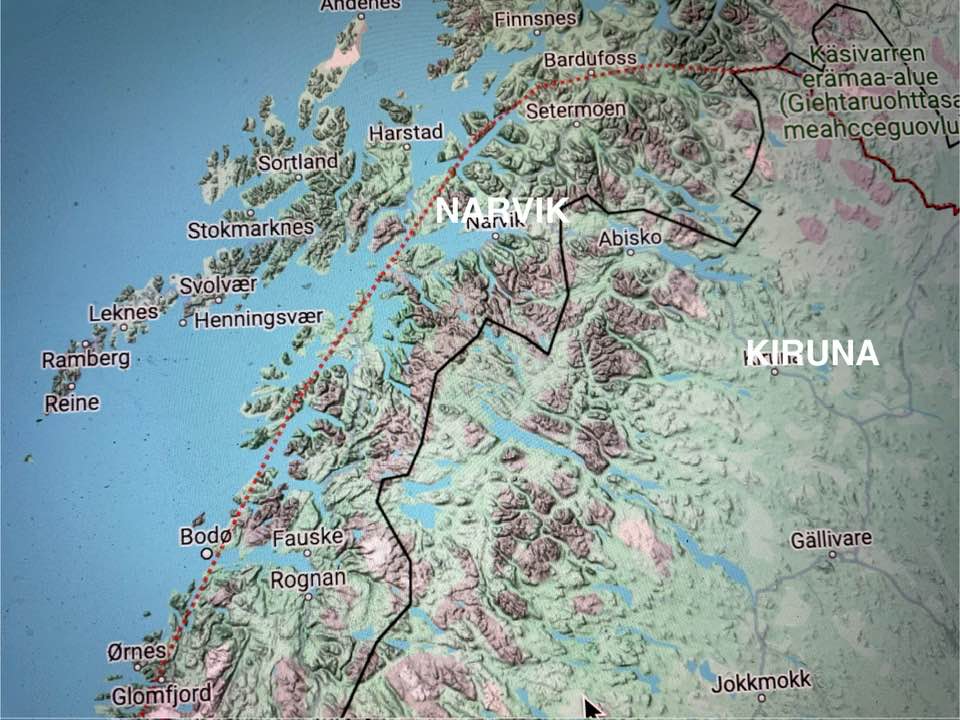

An example was the one I adopted for the American Birkebeiner X-C Ski Marathon one year long before Putin became “Tsar of All the Russias.” I pretended that I was part of a group of North American volunteers intent on rescuing Sweden from its Russian occupiers. I spent the first few kilometers of the 52 km race imagining the weeks that had preceded our extreme test of endurance; the current stage of our mission: skiing, with rifles and gear strapped to our backs, from our landing zone in Narvik, Norway, over the border mountains into Sweden and on to Kiruna, the country’s main northern rail and iron-ore mining hub (now the site of huge network server farms); a strategic site that had been seized by the Russian invaders during the first week of their takeover of Finland and Sweden. We volunteers were to launch a surprise attack on Russian positions surrounding Kiruna. As we liberated the north of Sweden, a consortium of regular armies from Sweden’s European friends and neighbors would free the south.

Most of us North American volunteers had Scandinavian ties of one sort or another and all of us were competitive x-c skiers. We’d been recruited by the Swedish government in exile in Ottawa (the rest of Europe was deemed too vulnerable to the Russians) and had trained in the mountains outside Calgary. The Canadians had then transported us to Iceland, where we transferred to Norwegian naval vessels that took us Narvik. There we disembarked and hit the ski trail.

As I passed the 25 km marker in the actual Birkebeiner Trail, surrounded by actual skiers from all over the (real) world, I imagined myself—all of us—being part of the “liberation” army heading for Sweden and a showdown with the . . . Russkis. However great my strain and output in that particular Birkebeiner race, the “metaphorical image” was infinitely more difficult. In the first place, in the metaphorical setting, we couldn’t just drop out. Rumor had passed up and down the ranks that to ensure discipline the colonel in charge of our rag-tag group of volunteers had ordered drop-outs and deserters to be shot—on the spot. Unlike competitors in a festive citizen’s race from Cable to Hayward, Wisconsin, we in our imaginary roles couldn’t decide, “I bit off more than I could chew; I’m too tired; I have a cramp in my calf; I just wanna quit.”[1] Lives were at stake; liberation of a wholly innocent nation state was on the line. We were skiing our way into history.

Furthermore, as bad luck would have it a flu virus had raged through our ranks on the passage to Narvik. A quarter of the volunteers had had to drop out of the mission before the rest of us could even slap our skis down on the trail leading east. Weighing on everyone now skiing hard toward battle was the possibility that the flu wasn’t yet done with us; that many of us would soon feel symptoms that would sap our strength, determination, and ability to go on. And what would the good colonel do then? Shoot everyone who was felled by the flu?

As my mind cycled through the image I’d created for myself, the same thought repeated: however hard I skied in reality; however exhausted I’d be at the finish line in reality, in my imaginary world, the “finish line” was merely the starting line. After skiing nearly 173 km across rugged terrain—more than three times the distance of the actual race I was in—I’d have to attack the Russians and fight till I dropped—either dead, wounded, or exhausted beyond consciousness.

The great thing about this “metaphorical image” was that when the actual finish line was within reach, euphoria set in: the effort could end at 52 not 173 km; I needn’t fear coming down with the flu—and being shot on the spot for desertion; and instead of having to confront the Russian army, I’d be welcomed by thousands of liberated “Swedes” lining the last 100 meters down the center of Hayward, cheering wildly and ringing their cowbells for us the liberators, who by our reputation alone had spooked the Russians into a hasty retreat all the way back to Russia. At the “Finnish” line, we’d be greeted by an allied army of volunteers offering us aid and chicken soup.

In the end, the image worked magnificently.

* * *

For some reason during my walk today, I thought about my “metaphorical imaging” of yore. Today’s pace was robust but nothing close to my “run rate” back in the halcyon days of workouts. At a walking pace, I was able to think far beyond the narrow effort in which I was engaged. I didn’t require some elaborate image to carry me through the hour-long walk. I could allow my mind to walk freely and independently of my feet and legs . . . and so it did.

While my body followed the sidewalks, then a well-worn path through Little Switzerland . . . and back . . . my mind wandered ahead to our cross-country train trip with our eight-year old granddaughter and behind to last summer’s unfinished project: an elaborate “gnome home” for our same travel companion. My mind pondered the memories to be generated on our odyssey; the train, our sleeping compartment, the dining car, fellow passengers we’re bound to meet; our 10-day visit with friends and relatives, with trips to the beach and lobster roll shacks, perhaps an overnight in New York City, and an array of other memorable experiences. My feet kept their own pace, while my mind thought more about creating memories; the importance of memories and how we build them, save them, retrieve them, and depend on them.

As my mind wandered according to its own impulses, it touched back to the impasse I’d reached with the gnome home. I’d been satisfied with where the design had led, but I’d reached a figurative cul-de-sac. I knew I wasn’t finished, but I was unsure where to go next with the project. Today, as my thoughts walked unleashed, they stumbled on the idea of designing, constructing the gnome home to “house” memories. What this means in practical terms I’ll explore in due course—most likely on the pages of a sketchbook in which I’ll experiment while I’m seated across from Illiana in our compartment as she draws and paints in her own sketchbook—and Beth reads a book and all three of us look up from time to time to see America zoom past our window. Today, however, thanks to a walking pace, not a running stride, my wandering thoughts broke through a long-standing impasse.

Stay tuned.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] In fact, in many ski marathons, you can’t “just quit” anywhere you like and walk to a nearby bus stop. Aid stations appear every so five or 10 kilometers, but you don’t want break a pole or a ski or your concentration too far from an aid station. Depending on weather conditions, you could be in for a long, treacherous slog through deep snows.

1 Comment

As I read this about your metaphorical battle, and being unable to drop out for any reason, I could not help but think of the Army Rangers who attacked Pointe du Hoc 80 years ago today. I long have marveled at the esprit de corps which makes young soldiers risk their lives, but those Rangers were in a different league all together. We should all remember D-Day. It was a big event in my family (my mother got the Bronze Star for her role in the D-Day invasion), but it seems to have been overlooked now by many people. And yet it has made the 75 year peace we have enjoyed possible. Nothing can repay their bravery.