MARCH 20, 2022 – Since the fall of the wall, Budapest has become a popular stop—or start—for Americans on leisurely, luxury, riverboat tours of Europe. “Buda” and “Pest,” facing each other across the Blue Danube, are rife with history rich in blood and treasure, destruction and resilience.

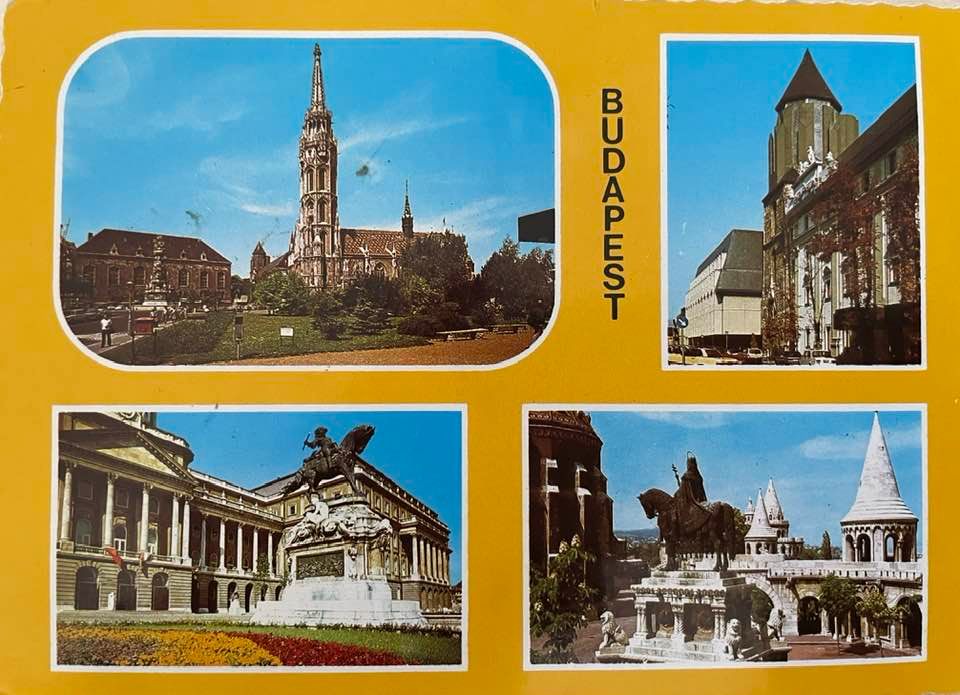

Even by 1981, this crown jewel of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire had been beautifully restored after the devastation of WW II. In a letter home, I expressed my impression gushingly: “It’s Europe’s first city architecturally, artistically, and scenically. I could spend weeks here. It’s so clean, so beautiful. Glorious churches stand everywhere, and much to my surprise, most are filled to the spire-tops with worshippers. I attended a mass in some anonymous but magnificent church. The music was overwhelming, and for a spell, the whole atmosphere carried me off to heaven itself.”

Music filled the air in Budapest. “I’ve never heard such fine music,” I wrote. “It was ubiquitous too—it flowed from Churches, drifted down from apartment studios, and echoed down the alley ways. On any tram one is likely to see a musician—violinist, cellist, horn-player or pianist.”

With an Hungarian émigré from Canada and her two traveling companions, I attended a Händel mass. Afterward, the expatriate (with vivid memories of the 1956 Uprising) gave us a guided tour of the Hungarian National Museum, then led us to a sumptuous meal of Magyar specialties at an upscale restaurant—where live, top-scale violinists provided entertainment. Joining us was the émigré’s brother-in-law, a heart surgeon in Budapest, who, like every other Hungarian, it seemed, played . . . the violin.

Among the sights of Budapest I observed an odd phenomenon: many bandaged hands, splinted wrists, arms in slings. They were so numerous I wondered if the lack of workplace safety was to blame. As much as the regime might regulate speech of the workers, I surmised, the Communists didn’t worry much about regulating worker safety; such a construct as OSHA found no traction in the workers’ paradise. Alternatively, I joked to myself, perhaps the walking wounded were simply overly zealous string-players.

The Hungarians with whom I interacted were friendly and accommodating, especially when my national identity was revealed. A sterling example was a man who spoke some English and whom I asked for directions. He not only directed me to the desired bus line but bought my ticket too. While he waited with me for the bus to arrive, I engaged in conversation, and in a letter home, I wrote about the exchange: “The man [. . .] had experienced the devastation of WW II. I asked how he now felt toward the Germans. His response: ‘The only difference between the East and West Germans is that I’m not obliged to like the West Germans.’ I thought that summed up the present as well as the past pretty succinctly.”

In Czechoslovakia and later in Poland, I’d encounter even more acerbic and telling variations of the theme denigrating the twin nemeses of Central Europeans in the 20th century: Germans and Russians.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson