FEBRUARY 5, 2022 – “Today,” I wrote, “is Easter Sunday, the 50th day of my ‘Trans Global Expedition.’” I then updated my family—the second time since leaving home. Smartphones—texts and email—were still a generation away.

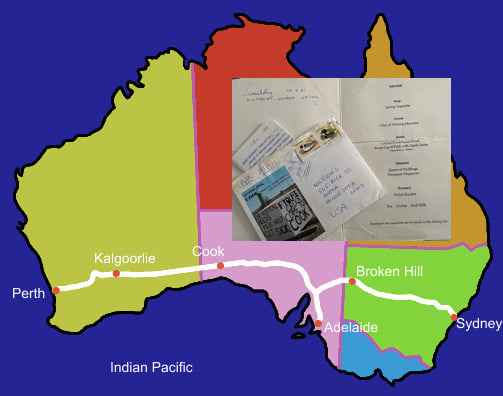

Aboard the Indian-Pacific I printed a 62-page letter on small pages (removed along sidelong perforations) from a pocket notebook. The letter carries no date except for my reference to Easter Sunday and the year—“1981”—in my mother’s hand, added after the dispatch arrived at my parents’ home.

I’m glad my mother saved the letter. Its capture of my impressions substituted photos . . . of which I have none. Had I traveled with a high-end camera and lots of film, or worse, a digital camera or smart phone of the modern age, I would’ve observed less deliberately. Modern devices would’ve produced an unmanageable volume of images in perpetual neglect of curation. The record of my trip would’ve become a jumble of slides, snapshots, or whole thumb drives—thousands of photos—in permanent repose inside forgotten shoeboxes on a closet shelf.

In the letter, I described the train as Australia’s “Orient Express” on which “we passengers are waited on like royalty and our accommodations rival the ‘Ritz.’” A diesel engine pulled five first-class carriages, another three second-class sleepers, two lounge cars, a dining car, two baggage wagons and a staff carriage. Fifty-odd passengers were aboard, and except for a few Englishmen and “Mr. Nalsson,” all were Aussies. Our shared journey was for the experience more than for the destination. Most of us were eccentrics by the end of the long trip . . . if we hadn’t been at the outset.

The well-polished, paneled corridors of the sleeper cars curved back and forth—a design I’ve seen on no other trains—and even in second-class, I luxuriated in royal comfort and regal treatment by the attendant—an Egyptian who’d attended Heidelberg University until Nasser had cut off funds, whereupon the promising student had emigrated to Australia for a better life. He assured me he’d found it, but discounting his words, at trip’s end, I left the good soul as generous a tip as I could muster.

My dining companions were odd and entertaining. The youngest, 23, was a train savant. He knew every possible detail about ours—its route, history, mechanical specifications—and insisted on sharing this information with everyone aboard. The oldest at my table I described as “a highly sophisticated Englishman who orders vin rouge with his evening tea.” Rounding out the group was a Queenslander “who talks and acts like an Agatha Christie character.”

Each of our three daily meals was an art form served from silver; not a morsel went to waste. Especially after dinner, our table group would join other travelers in the club car, where invariably, musicians aboard would turn out respectable renditions from an array of genres. I myself took a crack at the keyboard, morphing music into pantomime, much to the crowd’s delight—all while hurtling across the barrens.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2022 by Eric Nilsson

1 Comment

Now that I’m done working, I’ll dig through my trove of letters – some received 50 years so – and see how many from you are saved!

Comments are closed.