JULY 25, 2023 – (Cont.) Before lights out that Sunday night, I decided to fiddle with the old clock radio that Uncle Bruce had left behind on Parents’ Weekend. Despite my best efforts, however, I could not get the alarm buzzer to work, and it was the buzzer that I had anticipated deploying in order to wake myself before the dorm alarm bell woke the dead at 6:45 each morning. I hadn’t given the radio much thought, since there was precious little radio reception in that isolated region of Vermont. Under the circumstances, however, I decided to give it a try.

The only station that wasn’t broadcasting pure static was the CBC from Montreal, which came in loud and clear. There was serious talk going on, but the programming didn’t matter to me. I simply needed the radio to go off at a prescribed time just ahead of the dorm fire alarm. I set it, tested it, and set it again for 6:40 a.m.

At the appointed time the next morning, the clock radio came to life, only it wasn’t serious talk. It was classical music. A full five minutes worth. The next morning, it was the same thing, and the morning after that and the one after that, until one morning, I realized that I could not possibly live without classical music. It was a Eureka! moment.

Thanks to that old clock radio, I had come full circle from being saturated with music in my early years to my insurgency starting in about fourth grade and continuing into rebellion and outright, open, pitched battles with Mother and Dad during eighth grade. By the time they put me on the plane for Sterling School, my independence from classical music was complete. I had won the war over whether I should continue with the violin, which was what so deeply defined each of my three sisters; which was the great gift bestowed upon us by our beloved Grandpa Nilsson; which was the “language” that Mother and Dad spoke so well and encouraged in each of us. I had come to Sterling with a large trunk, an over-stuffed duffle bag, and a large suitcase, but left behind—forever, I was sure—was my violin case. Yet there I was, lying in bed each morning, finally hearing and feeling and understanding the magnificence of what my sisters, Mother and Dad had always known.

I would not let it go at that. When Uncle Bruce took me on an extended ski trip over Christmas vacation that year[1], we skied prominent ski areas up and down the state of Vermont. Never since have I skied so hard for so many consecutive days.

“What do you say,” he said over dinner one night, as he chewed, smacking noisily, “we go to Burlington tomorrow, maybe take in a movie or something.”

I didn’t want to admit that I too was from having skied my brains out the previous several days. “Sure,” I said. “I guess we could do that.”

The next morning we left the ski hostelry near Warren, Vermont and drove to Burlington. There we ate lunch at a home-style café, took in The Thomas Crown Affair and strolled past the storefronts on a street in downtown Burlington. By chance we encountered a classical record store.

“Hey, Uncle Bruce,” I said. “Let’s go in there.” Before he could answer, I retraced a couple of steps and walked into the store. Uncle Bruce followed me, uninterested in the place but patient with my newfound interest. He made no comment while I browsed through several bins of records.

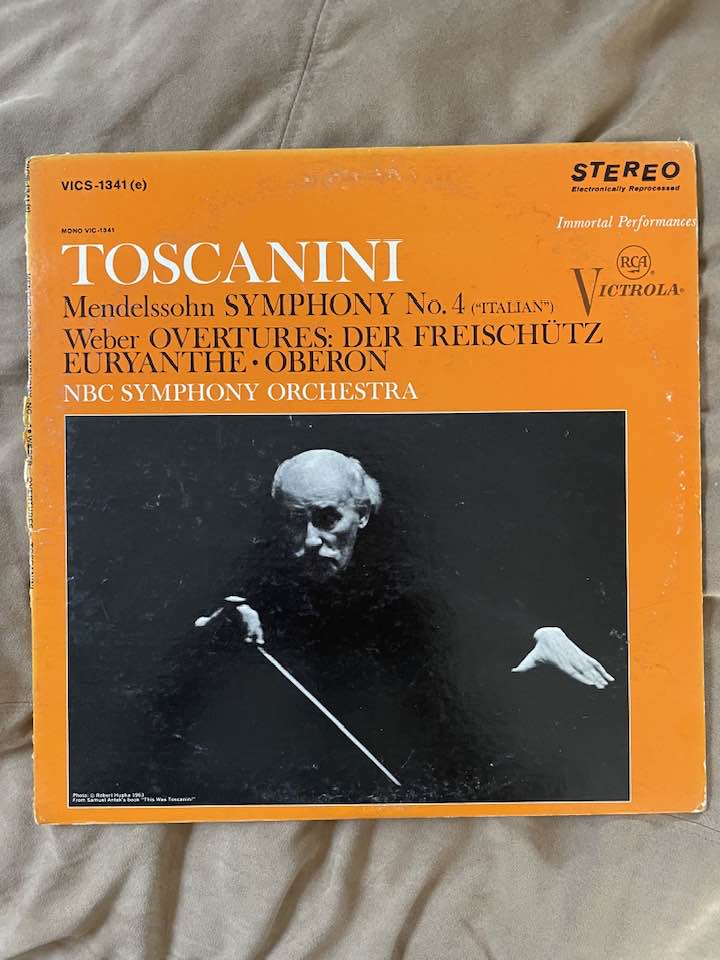

With my own pocket money I wound up purchasing two recordings of Arturo Toscanini conducting the NBC Orchestra in performances of Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony. I knew nothing about the pieces, but I had heard Dad rave many times about Maestro Toscanini and his unparalleled orchestra. Over the ensuing months back at Sterling, I would listen to those recordings until I had the music nearly memorized.

Nor would things stop with recordings. Already I’d hauled my violin back from Minnesota—it was in the back seat of the Mustang, well insulated by a million newspapers. Over the next several months I practiced more than I had over the previous four years. I would get so serious about the violin, I transferred to Interlochen Arts Academy for the remaining three years of high. I practiced hours every day during the school year and six to eight hours daily during vacations. I was determined to make up for lost time, even if I knew I could never catch my sisters.

All of this musical effort I could trace back to that old, malfunctioning clock radio that Uncle Bruce had dragged out of 42 Lincoln Avenue. Little did Uncle Bruce ever know what a profound effect his unwitting influence would have on my heart, mind, and soul and the future direction of my life.

In the meantime, however, Uncle Bruce took me skiing. Not only during Christmas vacation, but during spring vacation too, and not just to Hogback but to Stowe, Madonna Mountain, Middlebury Bowl, Glen Ellen, Sugarbush, and Mad River Glen. I skied every day at Sterling, as well, and by the end of the season, I was not the least bit embarrassed to be wearing a pig patch on my parka. I could ski better than most of the people who would laugh at it—or at Uncle Bruce for what he might wear or say or do.

* * *

That did not mean, however, that I was ready for the Sterling father-and-son camping weekend scheduled in late April. Through Mother, Uncle Bruce had caught wind of it.

Bam! Bam! Bam! came the knock on my dorm room door one evening after study hall. “N-I-L-S-S-O-N!” James Miles yelled from the other side. “T-E-L-E-P-H-O-N-E!” I was impressed that he would come all the way downstairs and to my door to inform me that I had a phone call waiting on the pay phone upstairs.

“Hello?”

“Uncle Bruce here!” he shouted over the phone. “Your mother tells me that they’re looking for people who can build campfires up there, but my question is, who’s going to bring the fire extinguishers?”

I felt panic. He wasn’t planning to go on the weekend camping trip, was he? In the half-second that it took me to gather my thoughts, I saw vivid images pass before my eyes: Uncle Bruce wearing his pork pie hat in the Vermont wilderness; Uncle Bruce going around using “proxy” on all the other adults on the trip; Uncle Bruce hauling an over-stuffed suitcase on . . . a camping trip; Uncle Bruce roasting marshmallows over an open fire—no, that was the one scene I couldn’t picture.

“Well, I don’t know if everyone gets to go,” I lied. It was a bad one. As the words tumbled out of my mouth, I realized how lame they were. Hell, Uncle Bruce was well aware that there were only 100 kids at the whole damn school. Of that small group, who, for crying out loud, wouldn’t “get to go”?

If he knew I was lying, it didn’t stop him. “Well find out where and when so I can make plans to drive up there. And let me know about the fire extinguisher. We’ve got a few extra ones in the warehouse.” He let out a loud laugh. I laughed too, but not at his humor. Mine was a nervous laugh. I was screwed.

As luck would have it, the camping trip got rained out before it even got underway. On account of unusually wet, stormy weather, the father-and-son trip was summarily canceled by the headmaster three days in advance of the event.

* * *

In early June, Uncle Bruce drove up to Craftsbury Common to transport me and my stuff to the outside world, specifically, down to New Jersey, where I’d spend a day or two at 42 Lincoln before flying home to Minnesota. The school and surroundings were as beautiful as ever, and though I was looking to my future, I felt a twinge of nostalgic sadness when the Mustang pulled away from Adams Hall and started down the road. Uncle Bruce had lowered the convertible top, and a bright sun smiled down on us as the Vermont countryside slid past. I was alone with my thoughts and said very little.

Eventually, we reached the Interstate and headed south. At some point, Uncle Bruce broke the silence and said, “When we get to Rutherford, you’re going to get your haircut.” Long hair was very much in, and though the rule-setters at Sterling were a strict bunch, there had definitely been hair creep over the course of the school year. No one’s hair length qualified him for hippiedom, to be sure, and my hair wasn’t nearly as long as it would grow during my college years, but it was longer than Uncle Bruce had ever seen it.

“Why do I have to get my haircut?” I asked.

“Because.”

“But why? Why should I have to get my haircut?”

The question made him cross, but his directive had made me cross. What business did he have forcing me to get my haircut?

“Because I said you have to. Gaga, Grandpa, your mother, your father. We all say you have to get your haircut.”

“But they haven’t even seen me in months. How do you know they all want me to get my haircut?”

“Because, they don’t like long hair.”

“But that’s not a reason. You have to give me a reason why I should have to get my haircut, when it has nothing to do with how I think or what kind of grades I get or anything.”

I had pushed things well over the edge. I could tell by the way Uncle Bruce pumped the accelerator. More than was his habit, he punched the accelerator, then let it up, pressed down hard again, let up, pressed, let up, and so on. “You want a reason?” he said. “Long hair is just plain wrong!”

I said nothing in reply. I realized that I could not argue with someone whose only argument was that “it was just plain wrong.” It would take many decades for me to understand just how wrong “just plain wrong” was—in the case of UB. But for much of the rest of the ride home, I stewed over what I considered to be a very cowardly response to what I thought was a fair question. I now viewed Uncle Bruce, and by extension, Gaga and Grandpa, and my parents, as overly prudish and conservative, and stuck in their ways. Nevertheless I wound up getting a haircut in Rutherford before heading home to Minnesota one or two days later.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Before our ski trip, I flew home to Minnesota for a few days leading up to Christmas. Early Saturday morning (following my late-night arrival), before anyone else in the household was awake, I crept downstairs and for the first time in my life put a recording of classical music on the stereo—sound turned way down. I remember the piece and performer: Zino Francescatti with the New York Phil performing Saint-Saëns Violin Concerto No. 3. I’d known for a while from correspondence that my sister Elsa was working on the piece for the annual concerto competition (which she soon thereafter won) at Interlochen Arts Academy. I wanted to hear the piece. A minute or two into the recording, Dad came downstairs, and still in his pajamas, he appeared at the sofa where I was seated. “Who put that on?” he said, the surprise in his countenance speaking volumes. –“I did,” I said. –“You did?” –“Uh huh.” I don’t think any kind of Christmas present could have given Dad greater delight.