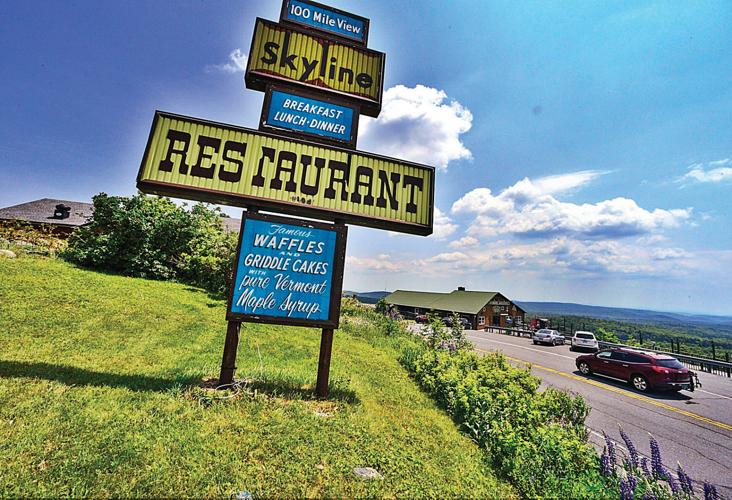

JULY 20, 2023 – (Cont.) Uncle Bruce rewarded my efforts—and his own—on the slopes by taking us to dinner at the Skyline Restaurant. It was a Dick Hamilton family operation, Uncle Bruce explained, and accordingly, Uncle Bruce and I were treated royally thanks to his long-standing friendship with them. The host and hostess, our waitress, the water-glass filler, the bus-boy—each of them, young and older, greeted Uncle Bruce like an old friend, each lit up when he proudly introduced me as his nephew, and each asked in earnest about our ski day. Uncle Bruce and I ate like kings too. I ordered “chicken consumé”—which, I decided, was a fancy name for chicken broth—and downed it along with three packages of sesame sticks before the main course: a delectable cut of roast beef, real mashed potatoes (not the watery kind that Mother made from a box of potato flakes) with real gravy (not the lumpy kind that Mother made from a package), and the greenest green beans I had ever laid eyes on. For dessert, I kept right on going with an extra large serving of apple crisp with a huge scoop of vanilla ice-cream on top—compliments of Dick Hamilton himself. Uncle Bruce ordered tea after dinner, and I washed everything down with a cup of hot cocoa—my sixth of the day.

That night I got sicker than a poisoned dog. I threw up all over the place, made a mess of things, and felt as if I had gone straight to hell without dying and wished to hell that I had died along the way, because surely the misery wouldn’t be as great if I had. Uncle Bruce handled it as if it were nothing, cleaned things up without complaint, and uttered not a negative word or hint of exasperation. The next day he took me to another of his ever-wider circle of Vermonter friends—Dr. Porter, a stocky, white-haired man sporting a white mustache. If Wee Moran was an elf, this guy was a short version of Geppetto. Uncle Bruce and the doctor talked like old chums, and in time I would learn that they had often skied together, until the previous winter, when at the age of 70-something, Dr. Porter had taken a spill and “knew right away that he had broken his tibia—the standard over-the-boot break,” according to Uncle Bruce. Dr. Porter asked me a million questions, and finally pronounced what I had already assumed: I had the stomach flu. He gave Uncle Bruce a bottle of pills to administer for my benefit, and after some brief talk between the men about the weather forecast and its effect on ski conditions, Uncle Bruce and I left the doctor’s office.

I spent the rest of the day in bed, moaning, groaning and drifting in and out of sleep. By that evening, I was feeling better, and Uncle Bruce took me to Dot’s Restaurant[1] (just down the block from Wee’s ski shop) where I had toast and soup and he ate a regular meal. But that night it was his turn to get deathly ill. It started when he literally rolled off the top bunk and landed on the floor next to my bed—kerplunk! Like a sack of stones. He lay there motionless, in a semi-fetal position, and I wondered what the hell was wrong with him. “Uncle Bruce. Uncle Bruce,” I whispered anxiously in the dark. The others in the room continued their snoring and slumber. He gave no answer. “Uncle Bruce!” I persisted, breaking out of my whisper. “Are you okay?”

He groaned, lightly at first, then more desperately. With a great struggle, he rose to his feet, pulled the ends of the belt to his bathrobe, which he had worn to bed, and strode toward the lavatory just outside the doorway of the dorm room. I heard him retch, followed by waves of heavy vomit splashing into the toilet water. I got out of bed myself and went into the bathroom after him. The place stank to high heaven. He was kneeling at the toilet, and he shivered something fierce. Next to him, on the floor, lay his thick wallet and a key-ring with lots of keys, and I wondered what they were doing there. I didn’t know what on earth to do about Uncle Bruce, but at least I knew that the keys and wallet couldn’t be left there. The act of picking them up gave me a small purpose and enough confidence to ask, “Do you want me to call a doctor?”

“No, don’t,” he said.

“But I can’t just leave you here. What should I do? What do you want me to do, Uncle Bruce?”

“Nothing. I don’t want you to do anything,” he said, struggling with the words, which competed with his urge to vomit. I was scared. I had largely recovered from my own bout with the flu, but in the dingy light of the shabby ski dorm bathroom, he now looked much worse than I imagined I had just 24 hours before. And what was the fall from bed all about? How could you fall like that and not hurt yourself? My splendid introduction to the wonder winter world of Vermont had turned into a mighty nightmare, and here in this terrible place, my Uncle Bruce—our Uncle Bruce—was in what seemed to be a fight for his life. How would I explain this to anyone? I thought, least of all to Gaga, Grandpa, Mother, Dad, my sisters? Or to the Whites, the Hamiltons, Wee Moran, Dr. Porter, all of whom had shown such affection for this man who was dying before my helpless eyes? And how would I get myself back to Minnesota, where clearly I belonged?

If I could have peered into the distant future just then—his, as well as my own—I would have found ironic comfort. However much Uncle Bruce could have used a doctor that night or on any number of critical occasions much later in life, he was then and was always quite beyond wanting help, and rather than panic as I did, with the advantage of hindsight I would have marveled at his strength and self-reliance, his desire to weather alone, every storm.

He recovered quickly, and together, we salvaged our inaugural ski vacation, despite another mishap involving severe frostbite of my hands, through which episode Mr. White literally held them, while Uncle Bruce looked on, offering not comfort or sympathy but expressing confidence that I would survive. I did.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson