JULY 22, 2023 – What is life but fate, and what is fate but randomness woven into meaning through the course of life. As the plane floated down onto the runway, marking the end of my Vermont ski trip with Uncle Bruce, I couldn’t have guessed that Vermont lay not behind me but in front of me and that a good many arbitrary events and encounters would someday become clearly linked and aligned, giving my life shape and meaning.

I can’t remember just what marked my decline and demise in the eighth grade at Anoka Junior High, but academically speaking, I was well on my way to becoming a disgrace to my family. I thought it was cool to act up in class, to engage in pranks, to “get the paddle” in front of a whole classroom, to get an “incomplete” in geography. Except, in truth, getting the “incomplete” really hurt me, because I loved geography. It was the teacher I couldn’t stand. He would give us inane assignments, like map-coloring, to perform in class while he went on long breaks.[1] Dad would later tell me that he had serious concern at the time as to whether I would ever graduate from high school. There was one bright spot, and that was my English class, which is where I was introduced to journal writing, through which, in turn, I realized how much I loved to write about the way I saw the world and my place in it.

My performance troubles in eighth grade did not go unnoticed. Mr. Nelson, the eighth grade counselor, called me in one day to find out “what the problem seemed to be,” since my prior academic and comportment records all through school had been exemplary. I don’t remember exactly what I said—or made up—but I do remember that Mr. Nelson seemed to be listening empathetically, and he earned my respect by not lecturing me. But by the conclusion of the school year, the jury was still very much out on my future. Mother and Dad were worried.

Then came the call. I remember the day well; a day in July 1968. It was cool and overcast outside, and the atmosphere indoors was dull and quiet. When the phone rang, I was sitting at the end of the sofa in the den of our house, browsing through some books off the overstuffed bookshelves that covered one wall of the room.

I answered. It was a woman who identified herself as so-and-so from the such-and-such office of the school district, and she asked me if I would have any interest in attending a boarding school located in . . .Vermont. I said yes and she said good and asked to speak with Mother. It was later revealed that a small, traditional boys prep school in Vermont was looking to expand the geographic representation of its total of 100 students in grades nine through 12. To put its money where its institutional mouth was, the school was offering full scholarships. Word had gone out to a number of districts, and somehow, the woman who called us on that cool, overcast day had gotten involved, and she, in turn, had talked to Mr. Nelson, and he, then, had mentioned me as a candidate who just might thrive in a radically different school environment from the one in which I had struggled.

When Mother hung up and asked in an encouraging way whether I would be interested in going away to a school in Vermont, I could barely contain my excitement. Go to school in Vermont? Get away from Anoka, Minnesota? I wasn’t just interested. I knew straight up that I wanted to go. After all, Nina had spent a year away at Connecticut College, and Elsa had also spent a year at Interlochen Arts Academy, a boarding school in northern Michigan. Both sisters seemed to be extremely happy living away from Anoka, Minnesota, so why couldn’t I be, as well?

Mother said the woman would get back to us. Oddly enough, neither Mother nor I had caught the name of the school, if we had even been told. I remember the two of us looking through the classified school ads in the back of several recent issues of the National Geographic, but the only Vermont school advertised was the Putney School.

That evening, while I was on the extension phone, Mother called Uncle Bruce to see if he knew of any prep schools in Vermont besides Putney, but he said he didn’t. I remember him saying, though, that if I were to attend school in Vermont, he would make sure that I got to ski at Hogback all that I wanted.

In any event, Mother and Dad conferred with me, and the next day Mother called the woman back with an affirmative response. A week or so later, Mother dropped me off with my sister Elsa at a school in St. Paul where the director of admissions for the Vermont school was interviewing candidates. Mother had some conflicting engagement and deputized my sister Elsa as my temporary guardian. This arrangement meant that Mother would not get to meet the admissions director.

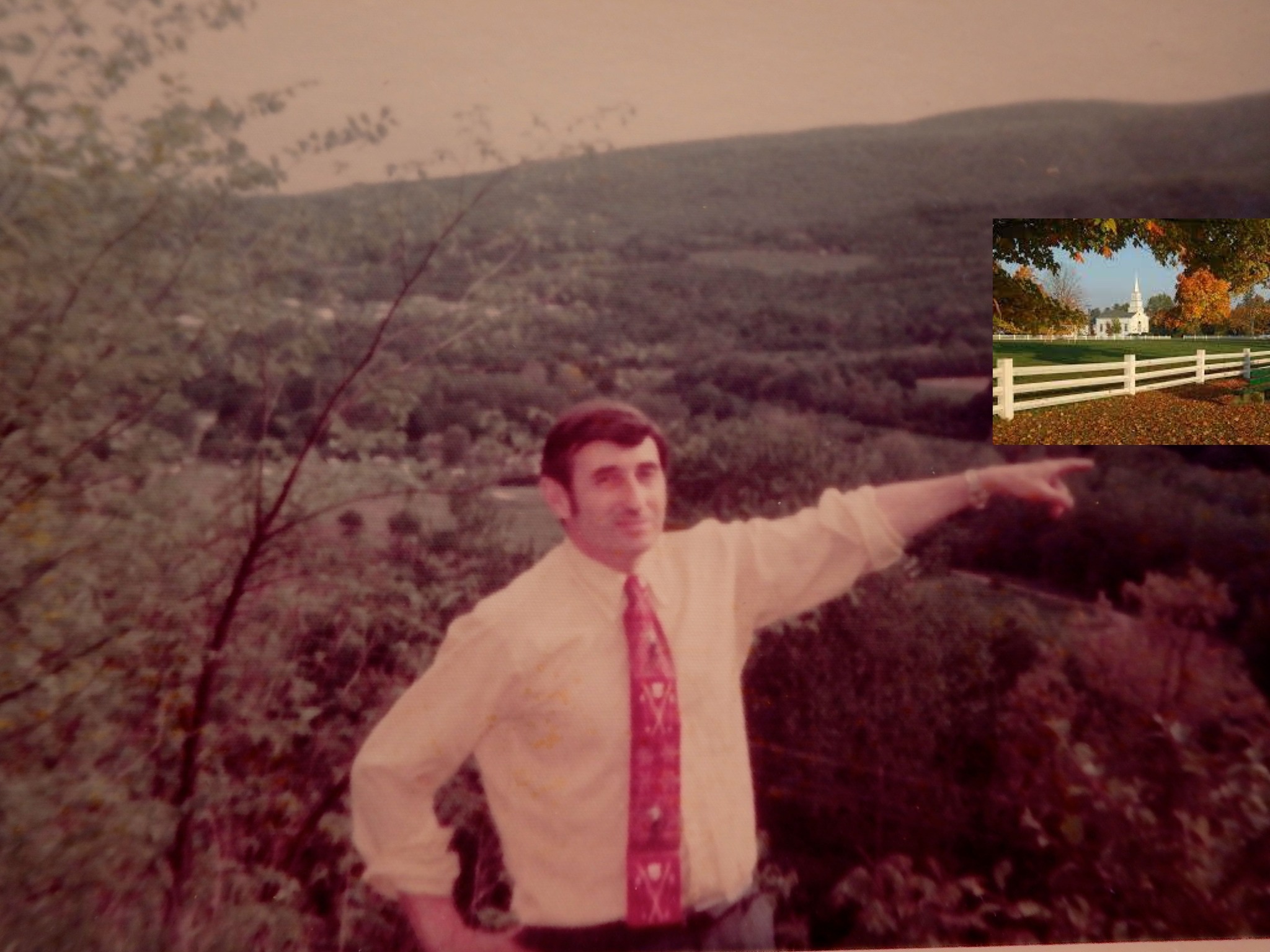

Just before the interview I was asked to complete a form and write a responsive essay to the question, “Why do you want to attend Sterling School?” So finally, the place had a name. I remember laying out the case—I liked politics, history, and geography, but those subjects weren’t very rewarding where I had been going to school, and I wanted to be in a school where other kids and the teachers liked those subjects too. Then I mentioned how I had an uncle who was part owner of a ski area in Vermont, and how I had skied there last winter, and how beautiful I thought the state was, and how much I wanted to get to know it better.

The director of admissions was Tom Bryant, and he wore nice clothes—a tie and sport jacket and shiny loafers, and he looked cool. He was cordial but not effusive, articulate but not loquacious, and he put me at ease. I learned that he was an alumnus of Yale, taught history, and coached the Sterling soccer team and the Sterling ski team. Of course, I mentioned Uncle Bruce’s connection with Vermont, and specifically, since Mr. Bryant was a skier, that Uncle Bruce was part owner of Hogback Ski Area. Mr. Bryant politely responded that he had not heard of it. I was disappointed and wondered what he might think of the pig on the patch.

At the conclusion of the interview, I had a good feeling about Sterling School, and on the way home, I read and re-read a 100 times, the school literature, which consisted of nothing more than a folded, double-sided, two-panel glossy brochure, with a small black and white photo at the top of the front panel, another photo on the back panel, and text over the rest of the hand-out. That was it.

Thus, in retrospect, with so little to go on, with Mother and Dad knowing, seeing, hearing absolutely nothing about the school, except what was disclosed by the brochure that I brought home[2], it is rather amazing, in retrospect, that when Mr. Bryant called our house a week later to inform me that I had been accepted, there was almost no discussion between me and Mother and Dad. It was settled: I would be attending the ninth grade at Sterling School in the tiny village of Craftsbury Common (pop. 100) in the northern reaches of the state, a part called, “The Northeast Kingdom,” to be exact.[3] I was ecstatic. Dad was relieved—relieved that I might graduate from high school after all. Mother was secure knowing that I’d be living in a state where Uncle Bruce had strong connections. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] He was also the stern swimming instructor at the Charles Horn Municipal Swimming Pool, where Mother forced my younger sister Jenny and me to take swimming lessons during the summer and where the water was always ice cold. Jenny, being cleverer than I, evaded the whole unpleasant experience by waiting for Mother to drive away after having dropped us off, then going around to the adjacent park, where she played for 45 minutes, then dunked her head in the drinking fountain, and reappeared in the swimming pool parking lot just before Mother returned. I, on the other hand, suffered through the lessons, leaving me all the more bitter when my geography class went awry under the same management.

[2] Later, in a “small world” discovery, my parents learned that the headmaster of Sterling, Edward Birmingham, was a close acquaintance of a former neighbor of ours. In an even “smaller world” occurrence, on the the first day of class at Sterling, my English instructor, Mr. Longfellow, had each of us 10 members of his class identify himself and his hometown. When I said, “Anoka, Minnesota [with a population of 10,000 at the time],” he exclaimed, “Anoka, Minnesota! I’m from Anoka, Minnesota.” About 10 years my senior, Mr. Longfellow had grown up on the other side of town; his parents knew my parents. After high school, he’d gone on to Harvard and after graduating, had landed a teaching job at Sterling. But the “smallest world” story connected to Sterling arose in the first day of English class at Interlochen Arts Academy, the small boarding school to which I transferred the next year—located in a remote part of Michigan a million miles from Sterling. Our instructor started with the same routine as Mr. Longfellow had the year before: “What’s your name and what’s your hometown?” The girl next to me informed us that she was from . . . Craftsbury Common, Vermont.

[3] Much later in life I learned that this appellation came from the fact that during the American Revolution, this northeast corner of what is now Vermont was inhabited by Tories.

1 Comment

And another small world…my husband, John, and I have connections in Vermont and love Craftsbury Common, although we know no one there, as the perfect place.

Comments are closed.