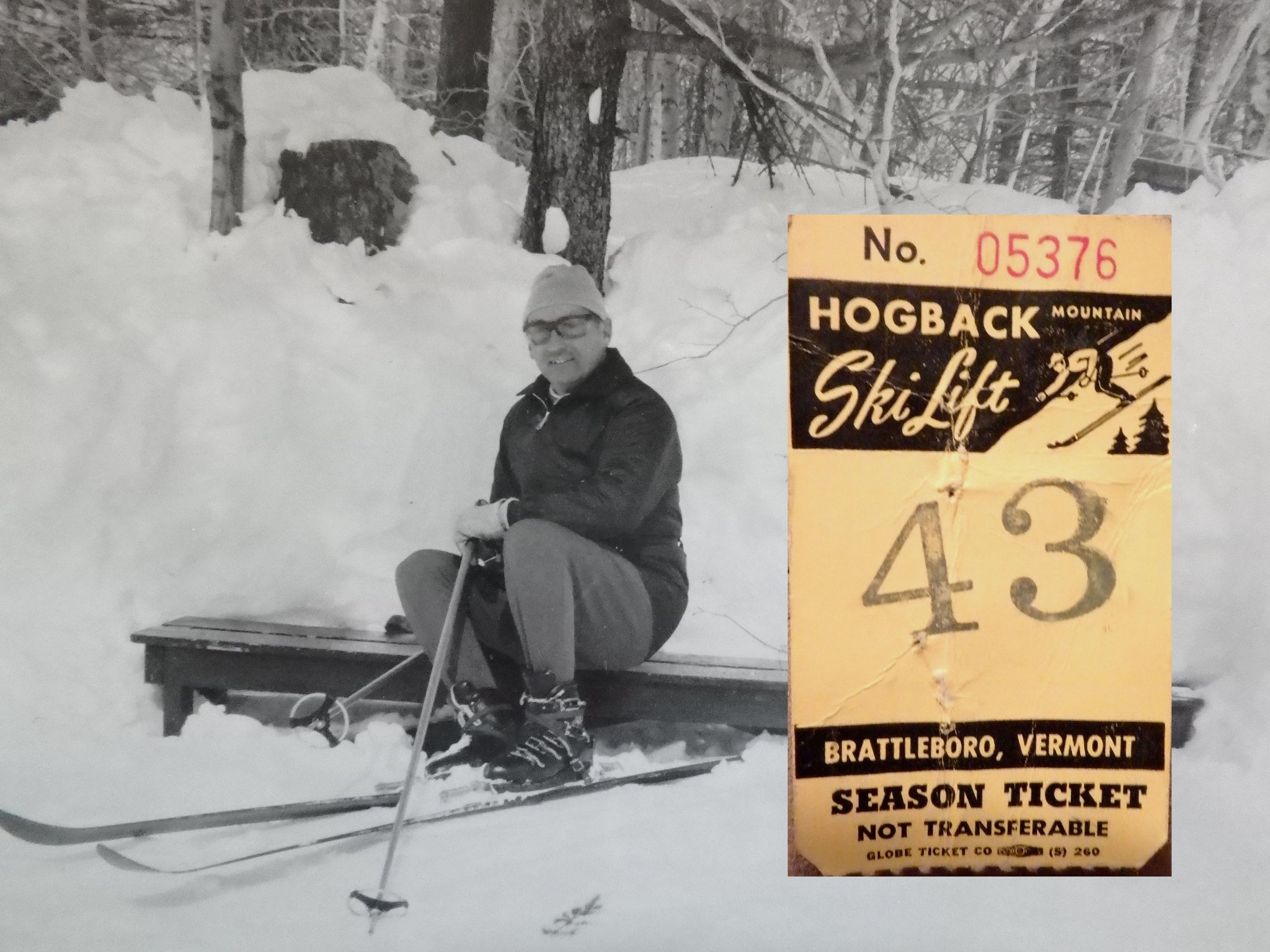

JULY 19, 2023 -(Cont.) The next day we drove east on Route 9 to Hogback Ski Area, officially in the town of Marlboro, except I didn’t see any sign of a town, just beautiful scenery in all directions and limited signs of development. There was the ski area on the south side of the big bend in the road, the Skyline Restaurant perched on the hillside on the opposite side of the highway, and at the other end of the bend, back on the south side, a small, white inn called the Marlboro Inn[1]. As Uncle Bruce had explained, a “hogback” was a geologic formation, and the ski area had been developed on the side of what the locals had long called “Hogback Mountain.”

When we pulled into the parking lot right off the highway, the first thing I noticed was a pick-up truck plowing snow energetically and sporting on the side of each door, a big, smiling, upright pig holding a pair of skis. I thought the name “Hogback” was a little odd, and the pig on the plow drove the point home. It seemed to go with the fact that Uncle Bruce himself could be a little odd at times, though I couldn’t always put my finger on it. Maybe it was everything together about him, or maybe it was just the opposite. Perhaps what made him seem a little peculiar were just a few individual signs of quirkiness, like the inside of his trunk and the mess in the backseat of his car, his frequent “me-oh-my,” and his repetitive whistling of the University of Minnesota fight song and a tune that had “Paris” in the title (so I was later told when I hummed it to my sisters), on the drive from New Jersey the day before and now again as he parked the car.

Anyway, I dared not say a thing, of course, about the pig mascot of Hogback Ski Area, but frankly I was disappointed that we weren’t at Haystack, Mt. Snow, or Stratton, which had been revealed as major ski areas by the SKI Guide and the brochures Uncle Bruce had sent me the previous year. I reminded myself that Hogback wasn’t even mentioned in the SKI Guide. But somehow Uncle Bruce had become well-connected to Hogback. At some stage, he had bought into what was a corporation owned by a few local stockholders, chaired by John Dunham, who was the magnate of Dunham Shoes, and managed by the Arnold Whites, whose family included a set of college girl twins who, Uncle Bruce informed me, were state champion ski racers, and the Dick Hamiltons (Dick Hamilton, according to Uncle Bruce, had been a fighter pilot and POW in World War II), who themselves were related to the Whites. Uncle Bruce had been elected to serve on the Board of Directors.

When we entered the modest lodge, called the Alpenglow, Uncle Bruce was on top of the world. A number of people greeted him warmly, and that touched off a series of introductions that lifted me, the kid from the flatlands of Minnesota, into this tightly-knit world of skiing Vermonters, and I savored it. It amazed me that Uncle Bruce, who lived with Gaga and Grandpa down in the hustle and bustle of paved-over New Jersey—Gaga, who I imagined had never had anything to do with the outdoors, and Grandpa who was all bihness and no play—would be in his element here at a Vermont ski area.

Arnold White was the lead character in a string of introductions. He exuded self-confidence and hospitality, and with an appealing Vermont accent, he launched right into cordial talk about how a “kid frahm cold Minnesota aught to feel right at home heah in Vahmont.” His big, alert blue eyes, rosy cheeks, flannel shirt, snow boots, and green Bavarian hat covered with ski pins gave him the convincing appearance of a guy who had landed exactly where he belonged in life. I liked him immediately and hung on every word of his ensuing exchange with Uncle Bruce.

“Yeah, wah doin’ just great with all the snow,” said Mr. White.

“Are we,” said Uncle Bruce. He beamed.

“Been a real chah to keep the pahkin’ lot cleahed, but that’s a great prahblem to hahve now isn’t it?”

“Are we keeping up with the grooming?” asked Uncle Bruce.

“Oh yeah. Dick’s out theah right now, I think, ovah on the Great White Way, so the ski school has a good place for clahsses this mahning.”

“How are ticket revenues so far?” asked Uncle Bruce.

“Oh I’d say weah way up fah the seasahn, and if the weathah fahcast is any indication, it aught to be just fine goin’ fahwahd. So Ahric,” Mr. White continued, looking at me, “is yah uncle Bruce gonna teach ya how to ski Vahmont style?” He laughed and winked at Uncle Bruce. Uncle Bruce laughed too.

“We’re going to sign him up for ski school. Is Erik Hammerlund teaching today?”

“Yeah, he is. He’s the best skiah in the state of Vahmont, ya know.”

“Yes, I know.” Uncle Bruce’s inflection was in full embrace of Mr. White’s assessment.

After the talk subsided and the Whites and Hamiltons got back to their tasks in running the place, Uncle Bruce and I got into our ski clothes. Uncle Bruce’s were in keeping with the style of the day (light green stretch pants and a belted parka), except for his tasseled beanie, which looked like Wee Moran’s and made Uncle Bruce himself look a little elfish, which, I thought, was appropriate for the proprietor of a ski shop, but not particularly stylish on the ski slopes. The word “eccentric” did not enter my young mind, but its meaning certainly did. But so be it, I thought. With or without the tasseled beanie, Uncle Bruce was clearly well regarded by these likable and authentic Vermonters, and that could only elevate his image in my view.

Outside, it took Uncle Bruce no time at all to spot the “best skiah in Vahmont”—Erik Hammerlund, who turned out to be a college student from Brattleboro. Erik recognized Uncle Bruce right away too, and in the cold, the two exchanged greetings warmly. “I want you to meet my nephew who came all the way from Minnesota to test out the skiing in Vermont,” Uncle Bruce said with ebullience. “His name is Eric too.”

“Really? Glad to meet you,” said the other Erik, as he removed his ski glove to extend a bare hand. I fumbled with my own gloves in order to shake his hand. I was impressed that he would go to the trouble. “You spell yours with a ‘c’ or a ‘k’?”

“With a ‘c,’” I said.

“Mine’s with a ‘k’. What’s your last name?”

“Nilsson.”

“Wow!” he said. “‘S-o-n’ or ‘s-e-n’?”

“‘S-o-n’”

“Hey, that means you’re a Swede just like me! My last name’s ‘Hammerlund,’ and I’m very happy to meet another Swede.” And to think that the “best skiah in Vahmont” also happened to be a very nice guy! I also found it interesting that he talked more like people I was used to than the Vermonters I had met so far.

“Are you teaching this morning?” asked Uncle Bruce.

Erik checked his watch. “Yes, I’ve got a class starting in just 20 minutes.”

“Great,” said Uncle Bruce. “I’d like to be sure that my nephew is in your class. Out in Minnesota, you know, they have lots of snow but they don’t have much in the way of mountains, and my nephew needs to learn from the expert how to ski on a mountain.”

After watching Erik Hammerlund ski that morning against the rugged scenery that beat to pieces the cornfields that bounded the ski areas back home, I had no doubt that he was indeed the “best skiah in Vahmont.” Over the ensuing week—after an unexpected hiatus, which I’ll explain in a bit—his clear, patient, one-on-one instruction would advance my proficiency far beyond where it had been on the ski hills—the ski bumps—back in the Upper Midwest. When I was not under Erik Hammerlund’s watchful instruction, I skied with Uncle Bruce, and I was as impressed by his ability as he was patient with mine. If he wasn’t a fancy skier, he was a solid one—smooth and confident, and he never fell. When I fell, he’d stop, wait for me to reassemble myself, and then offer a constructive pointer, invariably reinforcing what Erik Hammerlund had taught me—more often than not, “Keep your weight on the downhill ski.”

After that first day, I was utterly but happily exhausted, and much too tired to care when over a cup of hot cocoa, Uncle Bruce revealed to me that the photos in the Hogback Ski Area brochure, which, he said, had been his “assignment,” his “marketing project,” his “responsibility,” had been lifted from brochures for a ski area in Colorado[2]. He justified his misrepresentation—not to mention copyright infringement—by saying, “they were sufficiently doctored so that no one would ever know the difference.” Uncle Bruce laughed at his cleverness. Decades later, Cliff and I would laugh at another version of Uncle Bruce’s “clip art” cleverness. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson