JULY 18, 2023 – (Cont.) In mid-December the following year—1967—the annual Christmas package arrived from Rutherford. Gaga had put the usual, “Don’t open ’til Christmas” stickers on the outside, but from Christmases past, I knew that we didn’t have to worry: she had fully wrapped the presents inside the large parcel. Thus, with one of my sisters looking on in a supervisory role, I tore open the brown wrapping paper covering the big box and spread the gifts under the tree. But I noticed that among them was an envelope bearing Uncle Bruce’s large, direct, confident handwriting. It was addressed to me, and it said, “Merry Christmas to Eric from Uncle Bruce – open before Christmas.”

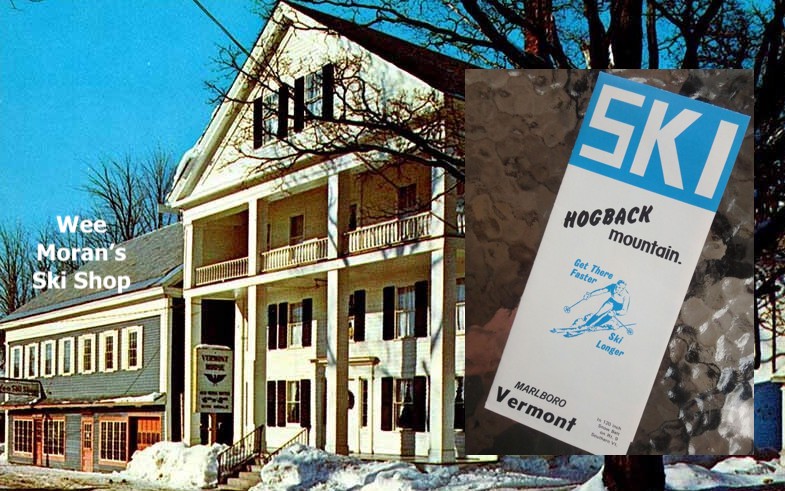

I opened it immediately, and inside was a brochure from Hogback Ski Area. Somehow by this time, probably by the regular correspondence that passed between Gaga and Uncle Bruce in New Jersey and us in Minnesota, I had learned that Uncle Bruce was one of the owners of Hogback Ski Area in Vermont. On the brochure he had written, “Welcome to Hogback—December 26 through January 6!” Behind the brochure was a plane ticket.

Never had I received such a present. On the evening of the day after Christmas, I flew to Newark, New Jersey, where Uncle Bruce picked me up in his new, blue-green, convertible Mustang. To be so lucky, not only to be taken skiing up in Vermont, but to drive there in a very cool, late model Mustang! No other adult in my life could match Uncle Bruce in the department of cool, and I had no trouble overlooking the remarkable mess in the trunk and Uncle Bruce repeating “me-oh-my” under his breath as he transferred stuff from the trunk to the equally messy back seat of the car in order to accommodate my modest-size suitcase. Uncle Bruce was my ticket. It didn’t matter that he seemed a little quirky.

I spent the night in Rutherford, and the next day, after Uncle Bruce had attended to some business and I had visited with Gaga in the house and followed Grandpa around in the warehouse offices, I rode north with Uncle Bruce to Vermont.

Soon after dark, we arrived in Wilmington, halfway between Bennington and Brattleboro. It was Uncle Bruce’s base of operations and apparently had been so for quite some time. We pulled up to the Wilmington Ski Shop, housed in a big, two-story frame structure right on Route 9 in the center of town. A sign extending out over the sidewalk hung above the entrance, and on the front of the building were large windows with many panes. Heavy snow was piled up along the street, and the snow banks in front of the ski shop were aglow with the cheerful light streaming from the ski shop. It had every aspect of a ski shop idealized by an illustrator. Uncle Bruce led me inside as if he owned the place, and if he didn’t actually own it, he was a good enough friend of the proprietor to pass for an owner. He would even help out by fielding questions from browsers and ringing up purchases for customers.

The real owner was one William Moran, except everyone called him “Wee”—everyone but Wee’s invalid wife who called him “William” and kept to herself in the spacious and well-appointed living quarters above the shop. On that trip and over the years that followed, Uncle Bruce and I would spend many hours visiting with Wee and his wife upstairs.[1] Although he was of medium height, Wee was the closest thing to an elf that you could ever find outside the imagination of a kid who believes in Santa.

Warm and outgoing, Wee sported slipper-like shoes with toes that curled upward, dark green work pants held up by suspenders over a T-shirt, and a tasseled-beanie atop his head, pulled down to his large ears. Curls of grayish white hair played around the edges of the beanie. Wire-rimmed spectacles rested on a convenient ledge atop the elf’s large, beak-like (but not unbecoming) nose, and he puffed incessantly on Camel cigarettes held close to the crotch between the index finger and middle finger of his large left hand as he rested the back of his right hand on his hip, level with his nicely proportioned paunch. He looked about 60 to me, a 13-year old kid.

I liked Wee the moment he shook my hand and greeted me with warm, confident words, which passed from a mouth that seemed to be deprived of a good many teeth, judging not from gaps I could see (I couldn’t) but from his inwardly turned lips and the sound of his voice. With the wizened speech of an elf, the unmistakable appearance of an elf, the job of an elf, and, for crying out loud, the name of an elf, Wee Moran—Uncle Bruce’s friend—most certainly had to be an elf.

But I later noticed that the elf must have been making lots of money. A brand new Mercedes was parked next to the ski shop, and Uncle Bruce told me it was Wee’s. He also told me that Wee rarely drove it, at least during the busy ski season. That was probably right. It was covered with a lot more snow than what had fallen recently.

I could tell by their banter and quick, familiar exchanges that Wee and Uncle Bruce were close friends, and in my impressionable mind, this relationship certainly spoke well of Uncle Bruce. We had landed at the busiest time of the season for the ski shop, and in the time that ensued, I got to see Wee in action with a number of customers, and it was a pure delight to watch him. He fitted people for rental equipment, answered questions about equipment for sale, and worked his magic vigorously behind his bench while customers waited for their skis to be waxed or bindings to be mounted or adjusted. He called every young woman, “Deb,” (for “debutante” he later told me and explained to me—a word with which other Minnesotans, I presumed, not I alone, were unacquainted), and he was as popular as could be with everyone who entered the shop.

In short order, Uncle Bruce also introduced me to “Faye,” who I thought went with Wee, until all was later explained to me. Faye looked a few years younger than Wee, wore a long skirt, loose blouse, scarf over her hair turning gray, and wire-rimmed glasses matching Wee’s. She ran the clothing department, as it were, and some other merchandise, including literature about organic food—something that I had not yet encountered back home in Minnesota, and which I suspected was the mark of someone who would disagree with how the adults in my family thought about the war in Vietnam. Over the years that I would revisit the Wilmington Ski Shop, Faye’s politics would become more evident to me, and they were definitely to the left of center. In any event, if she wasn’t as outgoing as Wee, she was kind toward me and friendly enough toward others. It surprised me to hear Uncle Bruce later describe her as being “a little up tight,” adding that “her stuff didn’t make much money for Wee.”

Uncle Bruce told me that he had seen Wee ski only once, out at Hogback, and that he was a novice at best. As I would observe first hand, however, Wee knew everything there was to know about ski equipment, and he was a highly skilled technician when it came to working on skis. In the midst of the rush of customers entering and exiting the shop, he managed to outfit me with top-of-the-line set of rental equipment. After gathering things up, Uncle Bruce and I took our leave to search for dinner and a place to stay. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] As Uncle Bruce would later inform me, Wee’s wife was an alumna of the University of Vermont, with a degree in philosophy. She and Wee showed great respect and affection for each other, though they exuded entirely different personalities. His wife was very thoughtful, soft-spoken and articulate. Wee, equally bright intellectually, was far more outgoing. They complemented each other well, and I loved the free-ranging and meaningful discussions that seemed to develop quite naturally when Uncle Bruce and I would visit after skiing and on some occasions, we’d even spend the night there.