JULY 17, 2023 – (Cont.) The next year would be the last year of Uncle Bruce’s Yuletide visits, but it was the first year that Uncle Bruce’s devotion to skiing crossed with my nascent interest in the sport . . .

. . . When Dad was a kid, he had owned a pair of very primitive wooden skis, with nothing for bindings except a single leather strap on each ski (a significant contrast, I noted to myself, with the sophisticated springs and cables on Uncle Bruce’s old skis up in the attic). Dad’s skis survived a number of decades, winding up in a corner of our garage. They were a curiosity for my sisters and me, and every once in awhile, I took the skis with us when we went sledding or tobogganing up at the local golf course. Elsa tried them once, negotiating her way down the hill successfully but not necessarily in any kind of control. I had several near-death experiences trying to use them. I would try only once or twice on each occasion, but I reached two conclusions from these experiments: first, it would be great fun to learn how to ski on real skis; and second, Uncle Bruce held a distinguished place in our family because it seemed that he did ski on real skis.

During that last Christmas visit of his, there came a typically wintry day when boredom reigned inside and there were no kids around—except Elsa, who wasn’t interested—to go with me all the way up to the municipal golf course, where there were some decent sledding hills. Out back, however, there was a small incline at the edge of our backyard. I was at the upper age of what modest fun it afforded a kid on a sled or saucer or, on that one occasion, Dad’s old pair of skis. After I had exhausted all the possibilities on the sled and saucer, I strapped on the skis, leaned forward, and let gravity draw me somewhat precariously down the incline. I repeated the downhill run, such as it was, several times, and noticed that Elsa and Uncle Bruce were watching from one of the back windows of the house.

Eventually I tired of the lack of speed and excitement and repaired to the warmth of the house. Elsa greeted me at the back door and said with her customary authority, “Uncle Bruce was watching you and said those skis aren’t any good and that you should be skiing on real skis.” Uncle Bruce soon confirmed the assessment, and went a step further. He told me that I ought to come out to Vermont with him sometime and take lessons from a certified ski instructor and really learn how to ski. It established in my mind that Uncle Bruce was an expert, that he knew what he was talking about, that indeed, he was a skier—something I dearly wanted to be and something that no one else in my immediate family aspired to, which, in turn created a new and special but entirely unspoken bond between Uncle Bruce and me.

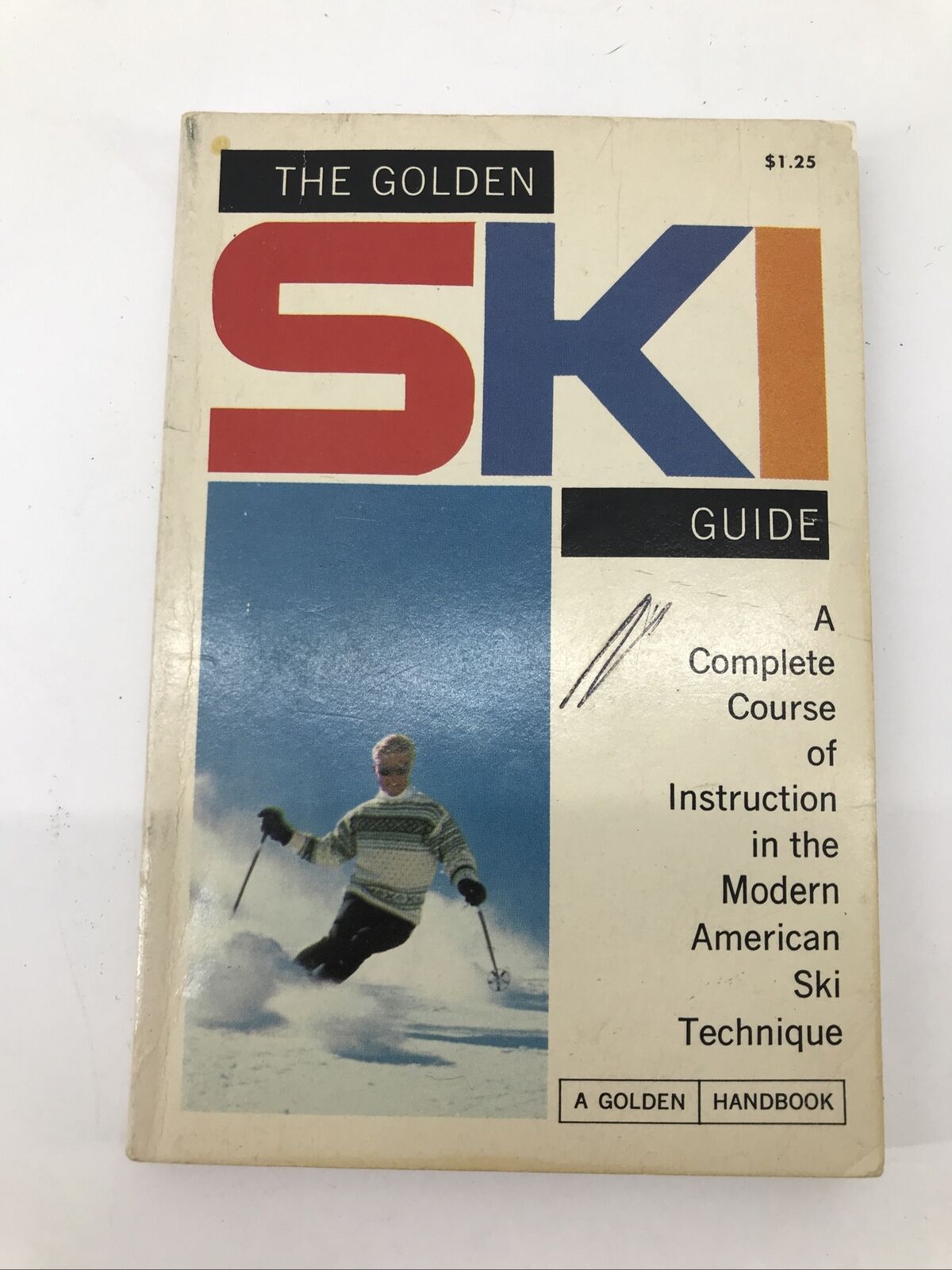

The next year for Christmas, Uncle Bruce sent me a small, paperback Golden book entitled, The Golden SKI Guide. Little could he have imagined what effect that book would have on me, and when much later, I showed him what I had learned from it, he seemed genuinely and thoroughly surprised. I must have read it 100 times, and I remember spending many a time after school, up in my room with the door closed so that my sisters wouldn’t make fun of me while I opened the book and practiced the snowplow, the stem-Christie, parallel turns, the wedeln,[1] and straight schussing.

I wanted to prepare myself fully for lessons with the “certified instructor” sometime, somewhere in Vermont. I gathered my savings and talked Mother and Dad into driving me down to the large, discount Holiday store in Fridley where I bought cheap ski equipment. As part of a carefully designed plan, I then joined the Anoka Junior High Ski Club and applied what I’d learned from Uncle Bruce’s SKI Guide. For me, that book was the bible of skiing, and the fact that it had come from Uncle Bruce reinforced my conviction that of all the members of our closely knit family, he was the coolest and the one whose example would lead me to skiing greatness far beyond the ski hills of the Upper Midwest.

At the back of the SKI Guide was a directory of all the major ski areas in the United States, and I memorized every detail of each area in Vermont—the name and location, the vertical drop, the number of runs, and the number of each kind of lift. I was determined to ski them all—if only Uncle Bruce would take me there. He sent me trail maps too, for Mt. Snow, Stratton Mountain, Haystack, and Hogback Ski Area, a strangely named place, I thought, which didn’t appear in the SKI Guide, and I pored over each of them, memorizing the layout of each place.

Unwittingly, Uncle Bruce had pulled away the curtains on my stuffy life, pushed up the window sash and opened my view onto the magical, wonderful world of skiing. That view so fired my imagination that when Mrs. Lindberg, my seventh grade English teacher, gave us an assignment to write an “adventure essay,” based on fact or fiction—every student had a choice—I wrote in earnest about getting lost in a terrible blizzard while skiing with Uncle Bruce on Stratton Mountain. It was all made up of course, because I had yet to set foot or ski in the state of Vermont. Thanks to the SKI Guide and the brochures from Uncle Bruce, I had supplied the essay with great detail, and Mrs. Lindberg was convinced that I had written it based on actual experience. She registered complete surprise when I told her that except for the name of the ski area and the name of my uncle, the essay was entirely fiction. She gave me an A+. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] A ski term of which several generations of skiers are mostly ignorant. It’s German for “wag” and describes the process of making many quick, parallel turns down a run.