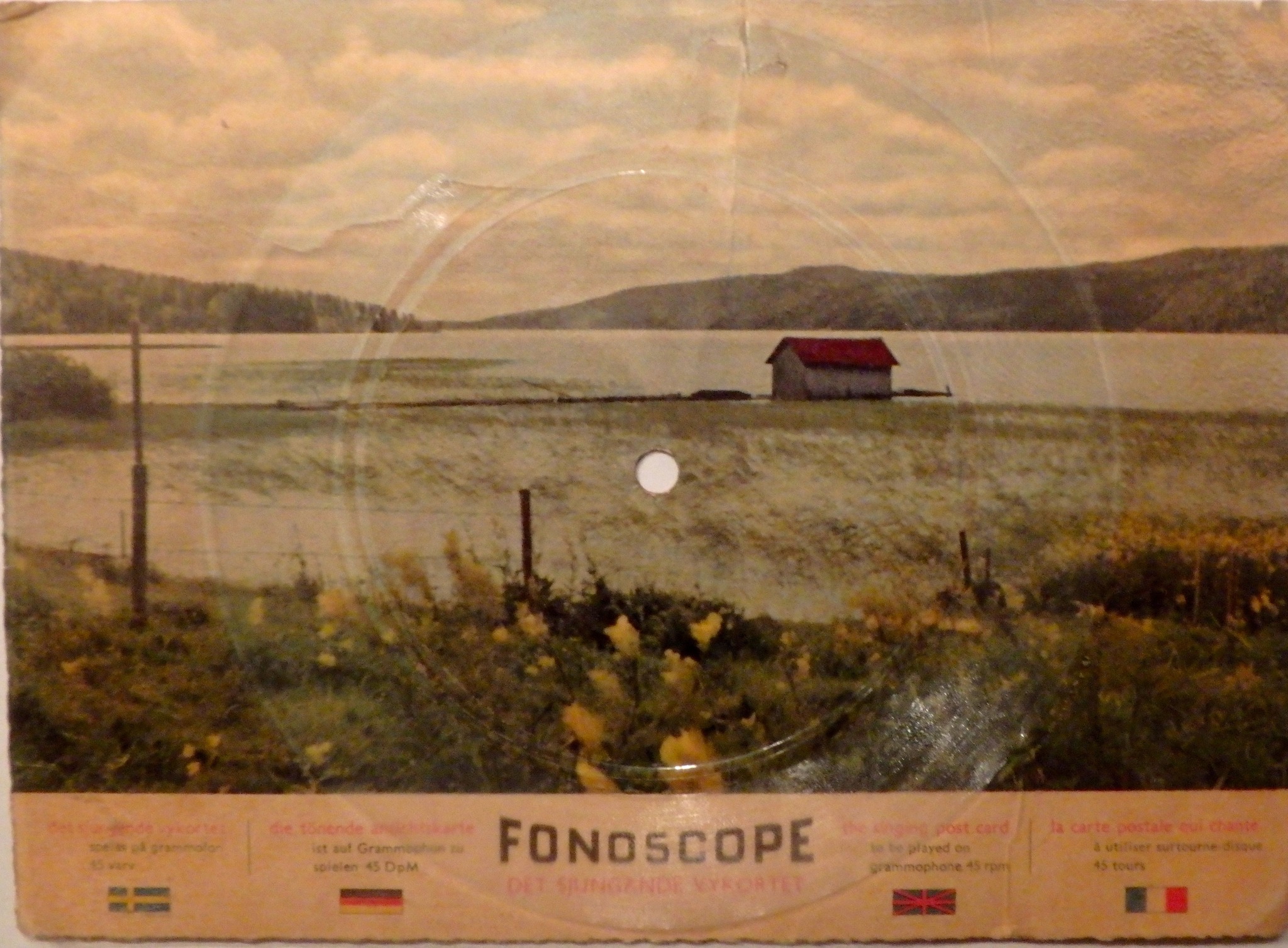

July 15, 2023 -(Cont.) After his appearance at the World’s Fair, we learned, Uncle Bruce traveled to Scandinavia and the United Kingdom. He sent post-cards to my sisters and me, and I regarded these as crown jewels within my collection of things. One of the post-cards, I remember, was quite large and doubled as a phonograph record. I didn’t know it at the time, but the recording happened to be of A Värmland, the unofficial Swedish national anthem, a sad, simple, beautiful melody. I knew it only as very Swedish music, and I liked it a lot, because it made me feel at once, melancholic (which I associated with greatness) and proud to be Swedish, and I played it many times on the phonograph that I shared with my sisters. It impressed me greatly that Ga, being from Sweden, of course, was familiar with music that Uncle Bruce—who was not Swedish—had sent us.

I was intrigued all around by Uncle Bruce’s obvious interest in Sweden, which was the “Nilsson’s country,” not the Holman’s, and by the fact that he had actually been there and my sisters and I had not. His interest in Sweden seemed to connect Mother’s non-Swedish side of the family to Dad’s side, and I liked that, because in my kid’s mind, it bridged the gap between the divergent backgrounds and personalities of the two sides of our family.

Actually, it was Uncle Bruce who was directly but unwittingly responsible for connecting the “Old World” but “newly arrived” half of our family with the “New World” but long-established part. Mother, of course, had ventured to Minnesota in the fall of 1945 to attend graduate school at the University of Minnesota. She roomed in a house on Sixth Avenue Southeast, just blocks from the center of Dinkytown, the thriving village-like commercial district that bordered the main campus of the university. Once Mother had settled into her academic routine, she lobbied Uncle Bruce to come west to get his MBA at the U of M. He did follow her, but he needed a room too, and so Mother, ever the one to call or call on people, took the initiative to find him accommodations, and the logical first step was to call on the folks next door who, she knew, let out rooms to male students. She rang the doorbell, and who should answer, but (the future) Dad. The rest was fate—or at a minimum, my existence and my sisters’ too.

Dad told me that Ga was very particular about whom she accepted as roomers. “She didn’t care if a fellow was black, yellow, white or orange, Jew, Catholic or Protestant,” he once told me, “as long as he wasn’t messy.” I don’t know how long Uncle Bruce roomed at my Nilsson grandparents’ house, but I never heard anything about him having been expelled for being “messy.” Thus, I must conclude that things got far worse as he got older.

In any event, I am left to believe that being a very curious sort and outgoing and interested in travel, Uncle Bruce was especially intrigued by this “foreigner,” Dad’s mother and the future “Ga,” who just happened to be Swedish. And that is how our uncle became so enamored of Sweden and why he chose to travel there.

It was befitting that during Uncle Bruce’s annual visit in the year that the movie Around the World in 80 Days had come out—a movie that both he and I liked a lot—I would play on my violin the melody of the theme from the soundtrack, and with great encouragement, he would ask me to play it again and again. Inspired by Uncle Bruce’s own interest in travel, I would one day go on to travel around the world, but though he himself would never circle the globe, over the years he took a number of trips back to Europe, and when in his 70s, he surprised me one day by saying he was thinking seriously of taking a trip to India. He never did go to India, but when he was all of 81, he took off on his own for London, Paris, and Switzerland, and for the most disturbing reasons, which can’t be divulged to the reader until later in the story, he even ventured to Serbia, if I can rely on the evidence of a photocopy of a plane ticket to Belgrade for one “Mr. G. Holman,” found amongst piles of other frightful evidence.

It was some of this other evidence—the taped telephone conversations—that revealed Uncle Bruce’s trips to Paris in 1960 (after his trip to Brussels, the UK and Scandinavia) in search of original “art,” which he and Mr. Jeppson, son-in-law of the then U.S. Senator from Utah, planned to sell back in the United States—to such outlets as Ben Franklin and W. F. Woolworth five and dime stores. The idea was to make original art “from Paris” affordable to hoi polloi. But because it was really bad art or members of target market simply weren’t interest in it, most of the inventory wound up in several large vaults in the Rutherford warehouses and much later, in the case of a few representative pieces, 42 Lincoln itself. I can only speculate as to how many times Uncle Bruce visited Paris and what else he might have been up to there, completely unbeknownst to anyone in the family.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson