SEPTEMBER 9, 2023 – As luck would have it, UB’s release from the hospital was slated for the end of the week, if he passed all his tests and his cardiologist approved. His confinement would afford me unfettered access to his chaotic files and papers. But first I had to rack up another round of frequent flyer miles on Northwest Airlines.

* * *

With the key Cliff had given me, I let myself into UB’s “beautiful mind” office. My mission was twofold: 1. Uncover and segregate all papers relating to my grandparents’ trusts and estates; and 2. In the course of #1, be observant about whatever else might surface. I found little in category #1 and an over-supply in category #2, particularly in regard to Western Union receipts. In just two months, another 30,000 pounds had sailed through cyberspace from Rutherford to London.

I decided that part of the solution to the dearth of information in category #1 was to drive to the Bergen County Courthouse in nearby Hackensack and search the real estate and surrogate (probate) court records for information. Cliff let me borrow his hulking van. I didn’t dare risk the van or my life on New Jersey’s tangled speedways, so I drove the slow but sure route.

The courthouse was a sprawling complex and with some effort I found the quarters from which to extract the desired information. At the surrogate court office, I encountered a two-step process. One involved searching a name index for case numbers—one for Gaga, the other for Grandpa; the second step required submission of the case number to a clerk who could then pull the files with all papers and orders filed to date. To my mild surprise, a probate case had been opened for each of my grandparents. At least UB had gotten that far, but again, Grandpa had died over 17 years before and Gaga had been dead for nearly 12.

From a micro-fiche screen I jotted the numbers down on a post-it note. Upon completing this simple task, I stared at the numbers. In the moment, my thoughts compressed two lives into a frightening reality: All the thoughts, words, hopes, fears, encounters, experiences, accomplishments, connections—everything that had made those two people interesting humans—had been distilled down to numerals on a three-inch-square of paper.

The post-it numbers, as it turned out, yielded little useful information about the status of the probate process. UB had filed wills and probate petitions and the court had issued letters testamentary. Not another finger had been lifted, and the wills were generic: whatever property was not already in my grandparents’ trusts was to be assigned to them. But where were the trust documents? No place that was yet illuminated.

According to the real estate records, according to the vesting deed filed in 1950, record title to 42 Lincoln—once the crown jewel of my great-grandparents’ property in Rutherford—was in my grandparents’ names. If a deed to their trusts had ever been executed, it hadn’t been recorded and it was nowhere to be found amidst the mounds of paper clutter back in Rutherford. If no recordable deed could be found, the house would have to be probated, but clearly UB, as executor, had abandoned his duties on that front.

Only slightly better informed than I’d been before entering the courthouse, I left the complex and found my way to Cliff’s van. When I turned the ignition key, it lit up an idea: why not visit the Holman warehouse just down the street from the courthouse? It was the place where Henry Holman’s side of the family had pursued business after settlement of the lawsuit between Henry and Grandpa back in the early 60s. To my knowledge no one from our side had ever set foot on the property since then—unless Mother had done so on a clandestine diplomatic mission to her Uncle Henry and cousin Bud during one of her visits to New Jersey.

Built in the 1930s, the towering warehouse looked like a well-groomed elderly gentleman in a suit bearing out-of-style lapels. Otherwise, however, the suit was neat, clean and perfectly serviceable. The lobby was the lining to the suit: intact and presentable but long out of style. Oil portraits of George B. Holman and Henry W. Holman, portrayed as titans, graced a wall. Conspicuously absent, of course, was any trace of Grandpa, whose brain power and work ethic had contributed so much to the success of the company and evolution of the trucking industry in the first half of the 20th century.

“May I help you?” the receptionist greeted me.

“Yeah, well, uh, maybe. I’m related to the owners, and I just happened to be in the neighborhood so I thought I’d drop in to say hello.”

“Well, Bob Holman runs the operations here, but he’s not here today because today’s Thursday, which is the day he spends on his boat. Bob was Bud’s son, named after his uncle, Robert Bruce Holman, who’d died over the Channel.

I’d met little Bob in 1964 when he was a maybe a first grader and I was 10 and visiting New Jersey with Jenny and Mother. Gaga and Mother had arranged somehow for Jenny and me to meet Bob and his sisters and their mother and grandmother. I remember little of the encounter except that while the ground-ups visited, we kids played in a great big yard awash in sunshine, taking time out only for cookies and lemonade.

Bob’s oldest sister, Katherine, I later discovered, was now in charge of the company’s headquarters, which had been relocated to Delaware, and she also served on the Board of Directors of United Van Lines—part of Grandpa’s legacy.

Just then another Holman employee appeared in the lobby; a gentleman who helped run things, who’d been around for a long time and even had a vague memory of having met Grandpa somewhere along the line. He offered to show me Bob’s office, right behind the lobby. If UB’s office was that of a “beautiful mind,” Bob’s lair was simply “executive neat.” Not a stitch of paper lay on the over-sized desk, and instead of bearing a UB-style repurposed soup can hand-labeled “PENCILS” and jammed with cheap pens, the desk was graced by a handsome pen and pencil set that was strictly for show. Also aboard the desktop were a couple of model United Van Lines trucks. I pictured the kid I’d met the summer of ’64—playing with toy trucks . . . and now with a boat that was no doubt a very big boy’s toy[1].

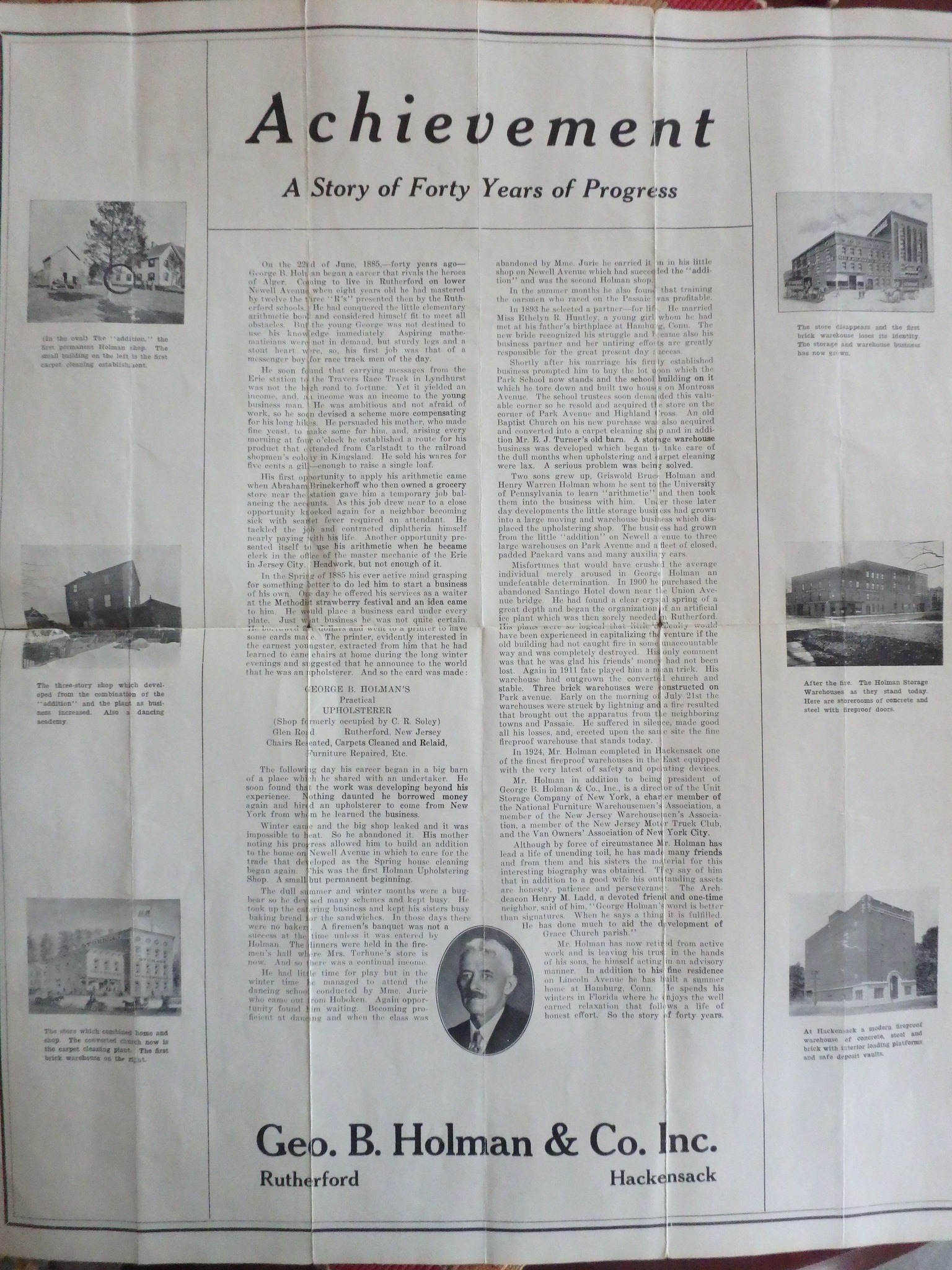

What impressed me most about the office, however, was treatment of the company history, commissioned by Grandpa back in the 1940s. Nicely framed and prominently displayed was the poster-size narrative starting with the Horatio Alger story of George B. Holman, the great grandfather of Bob and me, and how by George’s own shoe-strings he’d cobbled together the firm that developed into a major enterprise and one that Grandpa expanded after assuming the reins. Bordering the text, a progression of photos told the story of trucks and warehouses at various stages in the life of the company. A duplicate of the poster had hung in Grandpa’s Rutherford office back in the day (See 7/30/23 post).

I thanked the Hackensack Homan employee for his accommodation and asked him to greet Bob for me. With a twinge of envy, I drove Cliff’s van back to Rutherford.

A half hour later in UB’s office I resumed my search for “category 1” documents. Like Heinrich Schliemann at Troy, I kept excavating through one layer after another, not of clay, bricks, spearheads and pottery shards but into the documentary detritus of a disordered mind. The very bottom was the floor. An intermediate base line was the table top that served as UB’s principal “workspace.” It was hidden, however, under a large mound of paper, now calm but hopelessly disorganized as if by the past fury of tornadic winds. After an hour or so of sifting through layers of forms, cards, receipts, junk mail, statements, coupons, notices, reminders, advertisements, half-finished letters, several two-dollar bills, and hand-scribbled notes, I finally reached the surface of the table.

Or more precisely, I reached the bottom-most paper on the table top.

I nearly cried when I saw it except . . . first I laughed out loud. There lay “Schliemann’s Delight”: under all the bullshit was a copy of the very same history that in perfect condition was displayed with such pride and respect in Bob Holman’s office. The version before me was torn, creased, discolored, folded and after all, consigned to the bottom of the heap.

I sat back to ponder the contrasting destinies of the two branches of the family . . . over 100 years into the story begun by George B. Holman and Ethelyn H. Holman, one great-grandson was aboard his beautiful boat, enjoying the good life , while the other great-grandson was searching for answers inside the chaotic space of a “beautiful mind.”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Years later while going through my parents’ papers in Anoka, I encountered an invitation to a 100th anniversary celebration of the company. The affair had been orchestrated by the Henry Holman side of the family, and as I remember, it involved a dinner cruise aboard ship—presumably Bob’s—which, given the occasion, must’ve been a sizable vessel. Clearly Mother had received an invitation. I doubt very much that UB had.

1 Comment

Enjoyed reading your posting. My brother worked for a summer for George while in HS. You are right it is interesting how wealth is past down one side of the family and not to the other. Hope you find the answers to your family tree. George’s other 2 daughters maybe able to help you.

Comments are closed.