SEPTEMBER 23, 2023 – Though I’d predicted accurately that Mother would never ask to see Björnholm again, I was surprised that after we moved her hurriedly into an assisted living facility, she expressed no longing for the house at 505 Rice in Anoka. In fact, she returned to it but twice. The first time was a week or so after Elsa and Jenny helped her pack a small suitcase and carted her away shortly before Dad died: she asked to be taken on a quick trip back to the house to collect some “extra rolls of paper towels and a few dish rags” for her apartment. Once she’d collected them from the kitchen cupboards, she was ready to leave. A few months later she wanted to check on the status of my “archaeological dig.” Thirty minutes into that second visit, she’d seen enough. As we backed out of the driveway, she asked, “What are you going to do with all the recycling?”

That was it. That was the extent of her outward farewell—if that’s what it could be called—to the home that she and Dad had devoted countless hours to designing and re-designing; the house that during the construction phase Dad had inspected every day over his lunch hour and again in the evening[1]; the place that for half a century Mother and Dad had packed with memories and enough possessions to fill a United Van Lines fleet, where they’d accumulated an ocean freighter’s worth of books, letters, photos, CDs, fascinating memorabilia and box loads of papers documenting Mother’s intense involvement in a mind-numbing array of artistic, educational, religious, and charitable organizations.

As I combed through the record of Mother’s remarkable life, my previous awareness of her activities burgeoned into unbounded admiration and curiosity. Though by this time my relationship with her was frustrated by the chronic barrier of her mental disorders, I wanted as never before to “get her story.” If by temperament I would never be able to connect with her as I had with Dad from my earliest days to his last, at least I’d matured enough (I was now 56) to appreciate Mother’s accomplishments. What I didn’t fully recognize was perhaps her biggest achievement of all: overcoming her inherited mental disorders—at least until age had pushed them over the breakwater. But now it was too late. The almost constant storm surge inside her head had flooded all hope of “getting her story.”

It didn’t help that Mother lacked sentimentality. Her memory remained intact but her desire for recall had never been strong. Now it was bone dry.

It was around this time that I’d been contacted by Jean-Vi Lenthe, daughter of a Curtiss-Wright Cadette who was writing a sequel to her first book[2] about the group of select women aeronautical engineers during WW II. Mother had been among them. When Ms. Lenthe asked to interview Mother for the sequel, I was overjoyed. Now, finally, I’d hear the details of Mother’s wartime experience; her compressed, round-the-clock studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute; her work on propellor stress analyses at the Curtiss-Wright plant in Caldwell, New Jersey; her life-long friendships with other Curtiss-Wright Cadettes. I had to twist Mother’s arm to agree to the interview.

In the event, I experienced bitter disappointment. Mother clammed up something awful. Her only words were of self-diminution. “I don’t know why you’re so interested in my story,” she told Ms. Lenthe. “I did nothing special.” After half an hour of Mother’s holding to her conviction, the session ended, and the author packed up her notepad and recorder and empty handed headed back to her home in New Mexico.

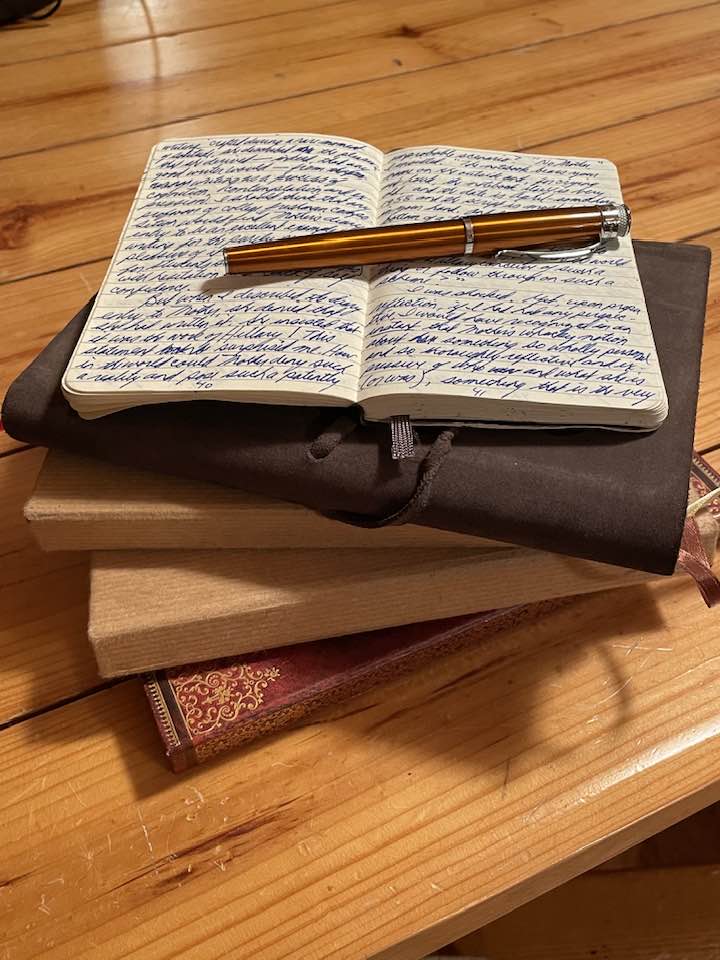

What I learned from the encounter was that Mother was not about to tell her own story. It was entirely left to us to construct from the vast record she’d boxed up and consigned to the attic of that big unoccupied house in Anoka. But Dad had also left an enormous cache of memories—years’ worth of daily journals, written in eminently legible and elegantly distinctive cursive; hundreds letters and wonderfully written essays and stories; thousands of photographs; and a sizable record of his own career and civic achievements. It was all too much to review and archive. I had to settle for boxing it up and storing it after labeling boxes in the most cursory way: exempli gratia, “MOTHER – JR. GREAT BOOKS”; “DAD – WRITINGS.”

Often I’d find a written gem that until I discovered it was unknown to all except its author. One such jewel found mention—and sparked musings—in my own daily journal:

Thursday, July 15, 2010

[. . .] To make conversation [with Mother] I mentioned what I had recently uncovered in the den or the attic. This mention was also to show Mother my newfound appreciation for all that she had done for us kids; for her brilliance, her contributions to the community; for her as a remarkable person all the way around.

In the event, I learned that I had over-estimated Mother’s sentimentality (she has none) and ability to accept a compliment (she can’t) and even her need for a compliment (that too is lacking). My effort to convey appreciation fell decidedly and resoundingly flat. My own need to compensate for years of what I feel has been an utter lack of appreciation, at best, and a reprehensible disrespect, at worst, was (“is”?) to remain unsatisfied. Mother is unable to accept the premise that she was brilliant, intelligent, lovingly wonderful and therefore, unable to understand my expression of admiration and gratitude.

The exemplary case in point was her reaction to my description of her diary entry for a day in April 1958. In that piece of superb writing crafted during a rare moment of solitude, she described the pleasure that she derived—indeed, that any good writer would—from writing as a process of cognition, contemplation, and expression. I should think that any professor of college freshman composition would find Mother’s diary entry to be an excellent example of writing for the purely personal pleasure of it and an inspiration for students struggling (perhaps) with hesitation and lack of self-confidence.

But when I described the diary entry to Mother, she denied that she had written it. She insisted that it was the work of Hillary![3] This statement surprised me. How in the world could Mother deny such a reality and pose such a patently improbably scenario?

“No, Mother,” I insisted. “The notebook bears your name on the outside and for crying out loud, the notebook itself is very old and the date is April-something 1958 and the script is most definitely in your hand. And I found it in the bottom of a trunk buried under haps of crap up in the attic where I don’t suppose Hillary ever ventured and for gosh sake, why in the world would Hillary conceive of such a thing or follow through on such a scheme?”

I was shocked. Yet, upon proper reflection, if I had had any perspective, I would have recognized in an instant that Mother’s whacky notion about something so wholly personal and so thoroughly reflective and expressive of who and what she is (or was), something that is the very embodiment of her heart, mind, and soul, can’t be helped. It is the product of the lack of sentimentality combined with the effects of old age mixed up with deeply entrenched psychological issues caught in the web of a mental disease.

As a consequence of Mother’s state, I am left to be disappointed. I possessed unrealistic expectations, wistfully concocted from the mix of my own idiosyncratic and woefully eccentric outlook on life, also borne of . . . an aging perspective “mixed up with deeply entrenched psychological issues caught in the web of . . . an inherited mental disease(?!).”

None of us can make Mother into something she isn’t. The record reveals what she was—brilliant, caring, generous, abundantly conscientious, and nurturing. Her gifts to us were enormous. That her mind has gone “wayward” as gauged by our standards cannot change what she once was. By the same token, we can’t very well allow ourselves to be disappointed by her lack of longing, her complete detachment from the past. After all, in addition to the factors that I outlined above, perhaps Mother’s unsatisfactory (to me anyway) reaction is her subconscious way of dealing with loss and grief.

Yet, Mother being Mother and I being I, my rumination about her was painfully confirmed before the ink was dry. Out of the blue during my next visit with her, she asked, “Do I have enough money?” (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] The new house was built on the large wooded lot adjacent to our then existing home at 503 Rice. Dad’s office at the courthouse was just a mile away in downtown Anoka.

[2] https://www.amazon.com/Flying-Into-Yesterday-Curtiss-Wright-Aeronautical/dp/097247031X

[3]Hillary, Nina’s oldest daughter, is a graduate of the esteemed Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University and a former AP special feature writer. Without question the most gifted writer in the family, she’s long been Garrison’s “go-to” reader, critic, and editor. Her style embodies the sardonic humor that she inherited from her late father, Dean, who himself was a humorously clever and prolific writer—despite (or “in spite of”?) being a C.P.A. specializing in corporate tax accounting.