AUGUST 5, 2023 – Of the four of them—Gaga, Grandpa Holman, UB and Mother—Gaga aged most gracefully, at least in the mental department[1]. Although she was the source of acerbic quips, she was always in control of her mind, which never veered toward the guardrails. Typical of her matter-of-factness was a side comment she uttered when one of my sisters was extolling the poetry of Rutherford’s most famous resident, William Carlos Williams[2], whose home and pediatric medical clinic were within an easy stroll of 42 Lincoln. If Gaga was a voracious reader of mysteries, I doubt that she’d been exposed to the modernistic and imagistic poetry of her esteemed neighbor. She did have encounters with his medical practice, however, when UB and Mother were children, and wasn’t impressed. “I sure hope he was a better poet than he was a doctor,” Gaga said in reaction to praise of his poetry.

Such a comment—uttered in the presence of her amused granddaughters—is what earned Elsa’s description of her as “a cross between Queen Victoria and Winston Churchill.”

Grandpa, as we have seen, aged less successfully than Gaga. Once brilliant and competent, he slipped and slid into self-absorption governed by obsessive compulsive routines. His tenacious hold on the past disguised the loss of his grip on present realities. “Txes, paprwrk, and the chllnge of fndng cmptnt hlp” were simply cover for his pointless affair with an adding machine and accounting paper in his dining room office late into the evenings.

UB? As I often described him in his last two decades, “He is the craziest sane person I’ve ever encountered.” Asked any question about the financial statements of a company in which he owned stock and he could talk circles around the company CFO—or the Chairman of the Board, whom he’d often button-hole at the annual meeting of shareholders and asked tough questions that prompted “I’ll have to get back to you on those” responses[3]. Listen to the scores of tape-recordings he made of his conversations with Alex, however, or peer into the four-foot high wall-to-wall garbage in the kitchen of 42 Lincoln, and you’d conclude that his mind was most definitely way past the guardrails.

Which left Mother, whose psychoses forced upon her a clinical diagnosis. Because she was Mother—or was it because she was a Holman?—she was odd and eccentric apart from the disease that landed her in the psych ward. As with Grandpa and UB, the “odd” and “eccentric” in Mother became more pronounced with age.

One of her multitude of idiosyncrasies was a penchant for putting things into plastic bags or wrapping them in Saran Wrap. If during a visit to Anoka she gave you anything to take home—a cookie, a newspaper clipping, a rabbit’s foot key chain she’d found when she was cleaning out your old bedroom closet—it was always set in plastic. Even much of her own stuff—a dust rag, stray pens, shoe polish—inevitably wound up inside a plastic bag.

A minor thing in the scheme of things but her plastic bag fetish was part of a larger pattern of behavior that was off-putting. Mother’s version of “off-putting” was inextricably bound to “odd” and “eccentric,” which in the estimation of my sisters and me, were linked to her psychological disposition, which, in turn, was driven at some level by the “Holman” gene generally and her psychiatric disorder specifically.

One manifestation of her “off-putting” was a personal policy of never complimenting her children’s achievements in adulthood. This contrasted markedly with her encouragement of our endeavors as students. After attending each of my winter house concerts from 2010 through 2019, the most I could expect from her was, “I can tell you enjoy playing the violin.” Likewise, when I showed her a carefully curated set of vacation photos I thought she—the former art institute docent—would appreciate, she said only, “I can tell you like showing your photos.”

One of her best put-downs came when she was 90 and we were discussing a family business matter. When she asked, “Who is our lawyer?” and I reminded her that I was a lawyer, she said, “No, I mean a real lawyer.”

I learned to be amused not offended by her snubs, but what frustrated my sisters and me most was Mother’s growing paranoia. People were always listening in, she believed, and watching, and when Garrison joined the family, Mother was particularly concerned about the mere mention of him or Jenny over the phone for fear the conversation would be overheard by someone of ill-will. In time she also became obsessed with “following the rules,” whether the “law” of Sunset, the group home or some other vaguely defined seat of authority.

Most of all, she was obsessed with following “Dad’s rules.” I remember one occasion in this realm that I wish I could forget, because I was actually mean toward Mother. Worse, I knew I was being mean in the very moments I was being so.

Mother and Dad were ensconced for a length of time at the cabin. On a hot, breezy summer Saturday, I hiked over from the Red Cabin (what my wife and I called our own place adjacent to the far end of Björnholm) just to say hello. Dad was in the garage working on some project. After a brief conversation, I continued on to check on Mother.

Despite the beautiful weather, she was inside, her Bible study materials spread out on the kitchen table. Bad sign. I’d noticed a correlation between periods of rising mental instability and Mother’s religious intensity. The fact she was actually reading and taking notes, however, was a good sign. At least she was still in an intellectual mode, not an emotionally-charged phase of praise and prayer—a precursor for the wheels coming all the way off.

The cabin was sealed up tighter than a drum. I couldn’t bear it given the gorgeous weather outside. “Why on a day like today, Mother,” I said, crashing into her study session, “are you inside with all the windows closed as tight as can be?”

“Your father wants it that way,” she answered assertively. “It helps keep the dust out.”

It was true—Dad was a neat nick—but so was the fact that “keeping the dust out” was just plain ridiculous on a day made in heaven for fair-weather sailors.

Without further ado, I opened the windows, one after another. “What are you doing?” said Mother with panic in her voice.

“I’m giving you some fresh air,” I said. I felt like a rogue sailor on shore leave out for some fun, taking a wharf-bound clipper ship for a joy ride around a spacious harbor. Mother made a start to close the windows I’d opened but there was no way she could move fast enough to keep up with me.

“Your father is going to be very upset,” she said with resignation. “What you’re doing is against the rules. It’s not right. Now stop, please.”

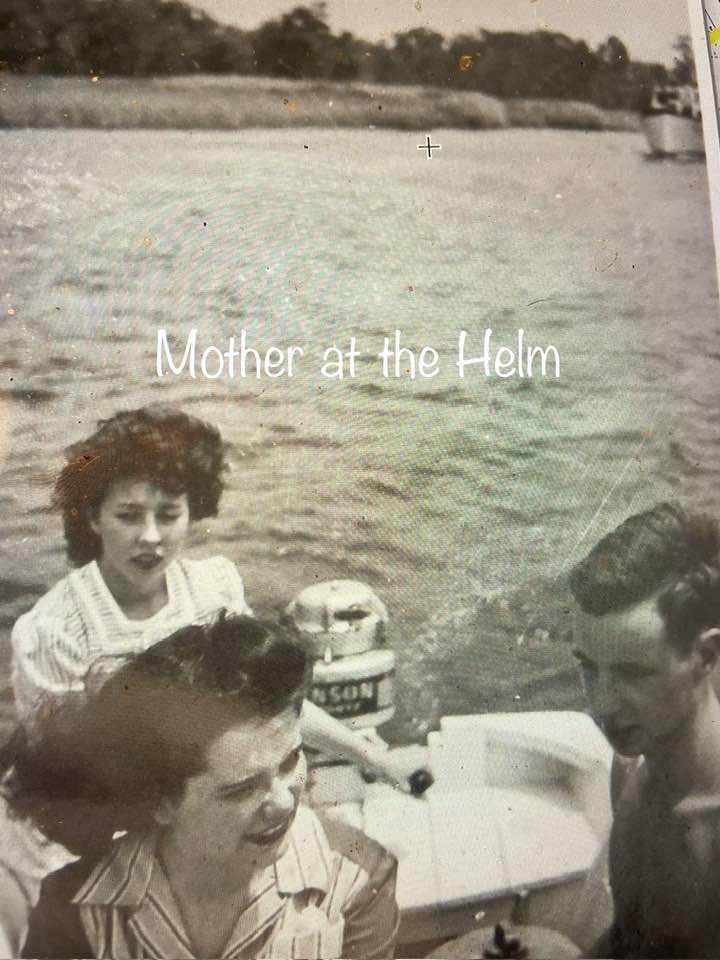

I did stop but only after all the windows were open and the pages of her Bibles were flapping in the fresh breeze that now swept into the cabin. The notebook paper, I imagined, was sail cloth waving over the deck as the ship moved away from the pier. I then exited the front of the cabin and headed back to the Red Cabin—like a prankster who had gotten the vessel under sail then jumped overboard and swum ashore before the shipwreck occurred. I knew what I’d done was mean, but I also felt sorry for Mother. In her youth she’d loved her hours sailing or motoring on Hamburg Cove and the Connecticut River just above the Sound.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] One of my all-time favorite photos, which I uncovered at 42 Lincoln. I call it the “Royal We.” It was taken at Gaga’s 97th birthday celebration. She looked a bit partied out.

[2] Williams was born in Rutherford 1883, two years before George B. Holman went into business, and died there in 1963. He was a graduate of Grandpa Holman’s university alma mater and is buried in the same cemetery as my great grandparents, grandparents and a portion of UB’s ashes. The photo here was taken of WCW striding in front of the old Rutherford library, which was visible from the side porch of 42 Lincoln.

[3] This photo was snapped in a lighter moment after the annual meeting of PSE&G. It captures UB presenting the chairman in 2012 with an original PSE&G bill from the 1930s.