AUGUST 2, 2023 – The past couple of days with Mother had been hell, and I imagine that they had been hell for her as well. For the time being, I was back in my office, tending to my law work. Just then, the phone rang. It was Elsa.

“Get this.” She cut right to the point. “I got this book called Psychological Disorders and read the chapter on manic depression[1]. Eric, I couldn’t believe it. I started reading the symptoms, and they’re really disturbing.”

“How’s that?” I asked.

“Ever hear of ‘hypergraphia’?”

“No. What’s that?” I silently rustled up my college Greek—hyper, meaning “lots of,” and graphia, meaning “writing,” but I wasn’t putting it in context.

“It means the compulsion to write.” Elsa didn’t need to explain any further. She knew that I knew Mother’s obsessive need to write things down, take notes, send letters. It worried me too. I thought of my daily diary and my own compulsion, two decades in the running, never to miss a single daily entry. And what about all the letter-writing I had done over the years?

“It gets better—or worse, depending on how you look at it,” Elsa said with continued urgency. “Another symptom, according to the book, is incessant talking. . .” I thought about Mother in the theatre, Mother at the cabin, Mother’s inability to sit quietly for more than two minutes. “. . . phoning people at all hours of the day and night.” Elsa continued to recite from the book. “Periods of ecstasy, periods of depression—well, I can’t say Mother has ever been depressed but, anyway—going to bed very late, not needing sleep.”

Elsa next reached the kicker symptom of Mother’s putative manic depression: “Then, Eric, are you ready for this? Hy-per-re-li-gi-o-si-ty.”

Neither one of us needed college Greek to understand the word and how well it described Mother. Its link to her mental illness shook my psyche. As a “believer,” a full subscriber to Christianity, and an active member of our neighborhood church, I knew full well that my current station in faith could be traced directly to Mother’s profound influence, to her heavy involvement in church, her frequent exhortations to pray and worship, give thanks and praise. Although I had lived through periods of rebellion and rejection, I was now firmly entrenched in my faith. But had my destination been determined not by God but by Mother’s mental illness? Or was Mother’s mental illness God’s way of directing me? However bizarre that might be, should I view it as miraculous or as a cruel joke? Could it be true that God was nothing more than a mental disease?[2]

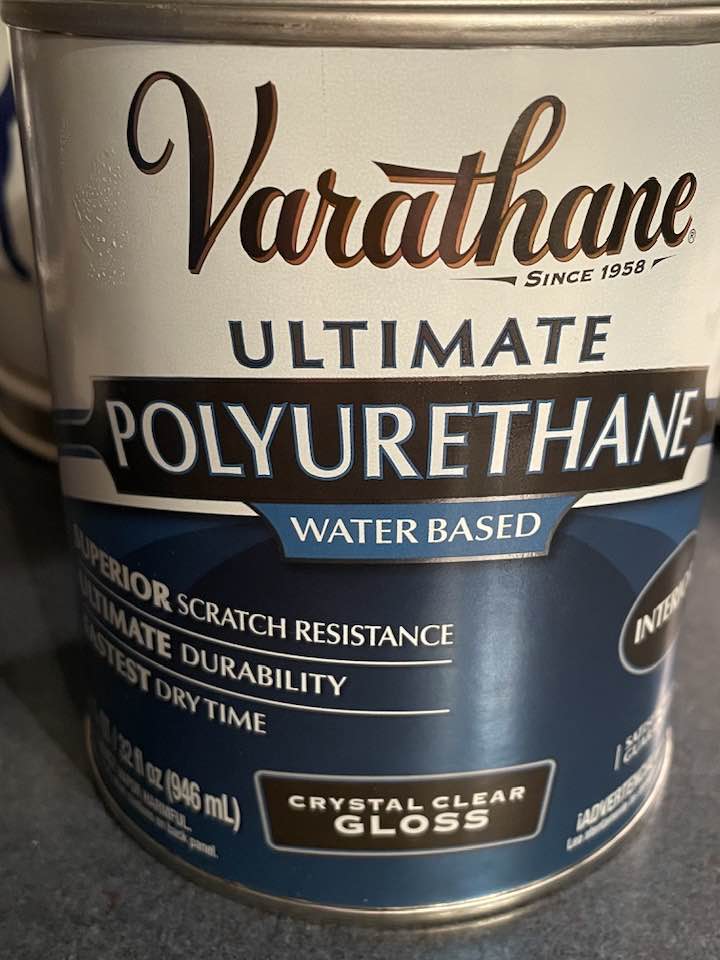

None of us knew it at the time, of course, but Mother’s psychosis had started days before when Dad was re-finishing the kitchen cabinets at their house in Anoka. Mother complained that the fumes were getting to her and she insisted on throwing the windows wide-open, much to Dad’s consternation. It was cold outside—why let all the heat go “straight out the window”? Whatever unpleasant effects the polyurethane might have had on Mother, her behavior was turning bizarre: calling people left and right on the phone, staying up till all hours of the night, racing around the house, singing as if she were on drugs, and most frightening—bearing a countenance that was not her own.

She flatly denied that she was mentally out of kilter, and to the extent anything was wrong, it was wholly attributable to the “varnish.” At the family’s insistence, she did go to her doctor, but she managed to convince him of her varnish theory. When each of us expressed continuing doubt about her theory, she went to the trouble of calling on a professor at the University of Minnesota who also fell under Mother’s remarkable intellectual spell boosted by her knowledge of chemistry. To show us our places, Mother got the professor to issue a written confirmation.

Despite her mixed-up state, Mother proceeded with plans to stay at a hotel in Florida, looking after Elsa’s daughter Linnea, while Elsa and her then husband, Chris, toured the state with their ensemble, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. The whole proposition had Elsa worried, but she had had no easy alternative.

Things got worse, and upon their return, Elsa informed me of Mother’s deteriorating behavior. Mother had accompanied Elsa’s family home from the airport and was still at their house, waiting for Dad to drive down to pick her up. That evening, things got worse. “Eric, Mother has gone completely nuts,” she said over the phone. “She was dancing in the street in front of the house minute ago, and Dad and I had to go out and pull her in, and now she’s running around and being totally bizarre. I think you’d better come over here.”

I jumped in the car and in fifteen minutes, I entered Elsa’s house. Mother was indeed off her rocker. “Eh-ric!” Mother said unnaturally, stretching out my name. She pressed her palms together and smiled at me with a crooked, tortured face. Then she grasped my hands. “Can we say a prayer?” A prayer? In her current state of mind? Repulsed, I wanted to draw them away, but I felt guilty for reacting that way, so I let her hold them. It was painful to see her. Her eyes were dark and crazed, and the possessed a look that I had seen in her face before she’d gone to Florida was even deeper now. Her outfit—her trademark (of late) blue, polyester skirt, jacket and white blouse—was soiled and disheveled. Her hair was a wreck. She was a wreck.

Just then, Elsa appeared, with Dad right behind her. He looked panic-stricken. “We need to talk,” Elsa said. I withdrew from Mother’s grasp and followed Elsa and Dad back into the kitchen. “Eric, I just can’t deal with this any further. I think we’re going to have to get Mother to the hospital. The question is how and where.”

We were clueless. Neither of us had faced anything like this before. But being a person of great practicality, Elsa assembled a short-order battle plan after a couple of phone calls to local hospitals. “Eric,” she said, “I think it’s going to take two of us to get Mother to the hospital. Today when we were driving home from the airport, at a stop light she actually tried to get out of the car.”

“You want me to drive?”

“Yes. Why don’t you drive. Dad can sit in the front with you and I’ll sit in the back with Mother.”

“Let me get her things together. You get her coat on and get her into the car.” It was ironic that Elsa was taking the lead role in all of this. Even the most casual observer within the family knew that her relationship with Mother had always been strained. Mother could be off-putting to all of us, but Elsa had a particularly difficult time with Mother’s oddball comments and personality. Yet as time passed, Elsa would move mountains and part waters for Mother’s care.

Together, Elsa, Dad and I escorted Mother to Fairview-Riverside Hospital, the closest hospital with a psych ward. It was about 15 minutes from Elsa’s house and just across the river from the main campus of the University of Minnesota, near the university’s West Bank. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] No longer caught in the catch-all net of “schizophrenia” and recognized as more than a “nervous breakdown,” manic depression was not yet “bipolar disorder,” at least in the lexicon of 1990.

[2] The full story of my expedition into and out of religion is a story unto itself. When I told a theologian about my crisis of faith arising from Mother’s diagnosis, he answered glibly that it was all a beautifully formed and presented test of faith. His response was less than convincing, and in time other factors colluded to dissipate my religious faith altogether.