JULY 10, 2023 – (Cont.) Back there in the dining room as I found it in 1980, I didn’t realize the full extent of the iceberg that had upset my perception of Grandpa. After all, what did I know? I was but the inexperienced grandson with a liberal arts education from a fancy school but only a passing glance with a practical education: evening accounting courses at the nearby commuter college, Farleigh Dickenson University.[1]

I left the “paprwrk” and focused on something far simpler: pens. I noticed an extraordinary number of them lying all about but not the kind of pens you’d want to use, collect or display; just cheap, ballpoint versions. I mean really cheap-ass pens (that’s what I called them to myself after a half-hour into the project)—the kind that back in the 60s and 70s were sold and customized in lots of 100 to advertise the local service station or dry cleaning store.

Amidst the chaos of the room, I found a shoebox stuffed with miscellaneous contents. Mindful of Grandpa’s reaction to my disposing of 30-year old magazines and 12-year old scrap metal, I decided to be more respectful of his haphazard pen collection and toss only the ones that no longer yielded any ink. I found a piece of scrap paper (“took” is the better verb, since most of the careening piles of paper were “scrap”) and used it as a test sheet. If the pen produced ink, the instrument went into the shoebox (which I’d respectfully relieved of its previous holdings). If the pen was dry, it bounced off the compacted contents of a token wastebasket, which no longer had any capacity for additional waste. At first I kept count—so many pens into the shoe box, so many on the floor surrounding the basket—but after a few dozen going this way and that, I lost track.

I should not have been surprised when Grandpa appeared out of nowhere. “Hey, hy, hy, wht r yu dng hr!”

“Grandpa!” I said, nearly choking on my saliva. “I’m just going through all your pens and saving the ones that work and tossing the ones that don’t.”

“No, no, no. Yu cnt do tht.”

“But Grandpa,” I said, trying to regain my composure, “these don’t work, see?” I pulled several from the wastebasket, and one at a time, worked them in a scribbling pattern over the piece of test scrap paper. “See? These don’t work. They’re all dried up.”

“Yeah, bt I cn gt reflls fr thse.”

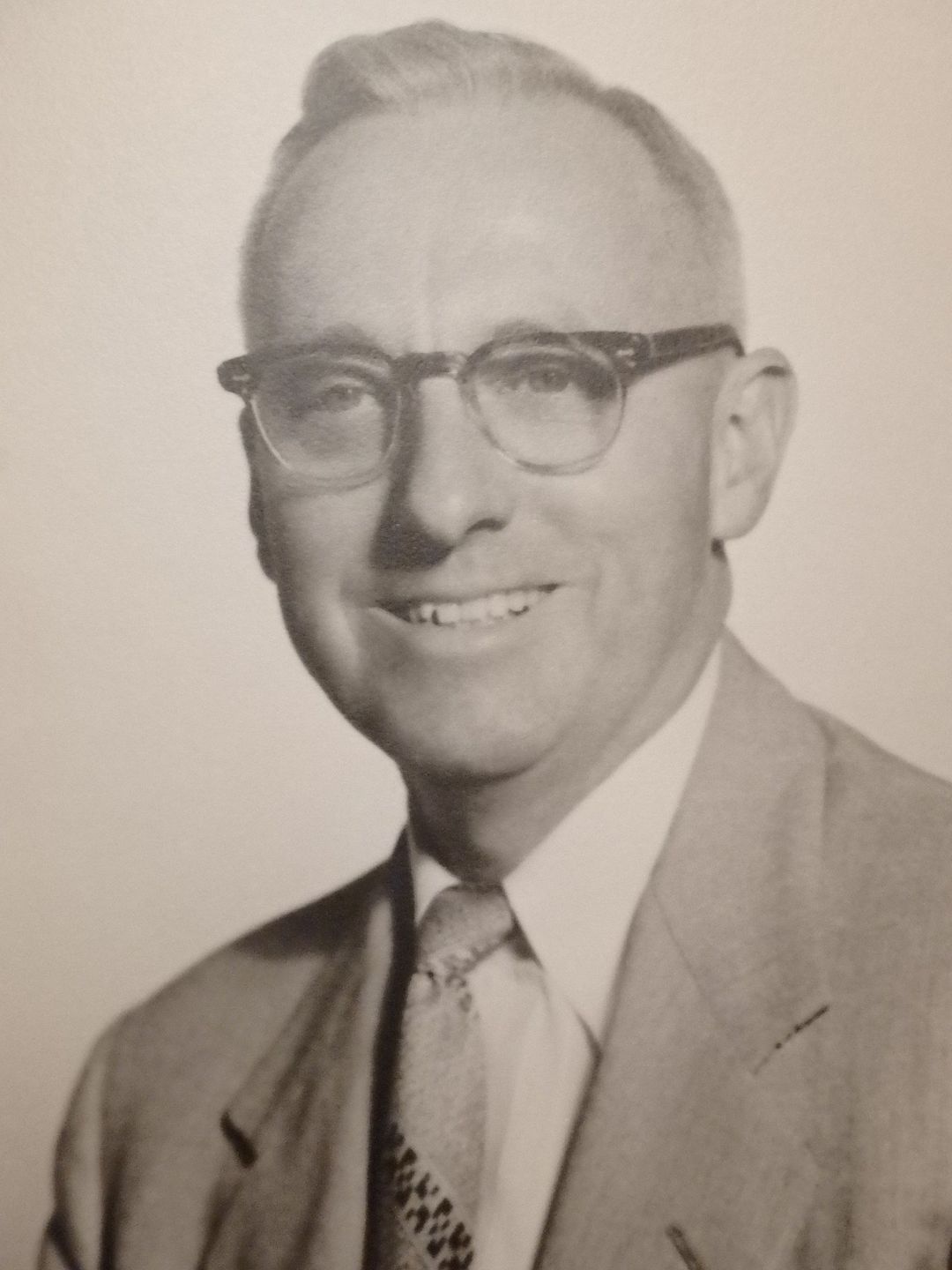

These confrontations with Grandpa over pens, scrap metal, and ancient periodicals were extremely difficult for me. I was barely 25 years old, and if it was impossible to have any kind of idealized grandfather-grandson relationship with him, I admired and respected all that he seemed to have accomplished in his life. If Grandpa was obsessive-compulsive about “pns,” “paprwrk” and salvaged truck panels that “cld be usd fr anthr grge rf smday,” in what I realized was a greatly down-sized business, he’d once been a very gifted, highly regarded man in a wide range of civic and business affairs. My sisters and I knew this from what we had been told and from all the photos, plaques, and awards that filled his office; from excerpts and photos[2] in histories of the trucking industry; from newspaper articles about his selection as Rutherford’s “Man of the Year”; and from the testimonials at my grandparents’ 50th wedding anniversary dinner, which Gaga, Mother, UB, my two older sisters, and I attended.[3] But I also learned about this career from a discovery I made one day while organizing another corner of the house.

Again with Gaga’s strong encouragement, I decided to tackle the jumble of files, boxes, and papers in the old “billiard room,” of Gaga and Grandpa’s house. Formerly a chamber designed and appointed for social gatherings, the party room was now one big, unorganized storage facility. It took the better part of two weeks to sort through things and give the space some semblance of order.

One day, in the course of sifting through a steel file cabinet that had been moved from the warehouse offices, I discovered a folder full of printed texts. Some were typed, some were written by Grandpa’s hand—with a high-quality pen. I sat down to read them and soon realized that they were speeches; speeches that over the decades Grandpa had delivered at various conventions and other business gatherings. Judging by the sweeping messages, many of the speeches appeared to be keynote addresses delivered to large audiences. I did not retain any copies, and as the reader will discover, I have good reason to fear those orations were later lost or destroyed.

What I can remember, however, is my reaction to Grandpa’s superb command of the language. He was a brilliant writer if not a brilliant speaker, and however much he might have elevated an education in the principles of finance and accounting over the study of poetry and literature, his pen would have been the envy of any English major. As frustrated or even disillusioned I might have become with him by that time in my life, I realized then and there just how gifted the man had most certainly been, and how much he had contributed to the business of our nation. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Ironically, Grandpa went “Ivy League” on me when it came to law school. I’ll never forget the phone conversation with him while I was home on spring break my senior year of college. After he and Mother and talked for a while, Mother passed the receiver to me, whereupon he asked, “So, where are we [as in the royal we] going to law school?” Upon hearing, “William Mitchell,” a St. Paul school with a good local reputation, and to which my father, a court administrator who knew a great many lawyers, had steered me, Grandpa was quick to register his consternation. “No, no, no. I’ve nvr hoid of tht. We shld be gng to Hrvrd, Yle, UPenn [his own alma mater].” His disappointed voice trailed off. I was crestfallen.

[2] These included an early company truck, one of the first “semis” every built, which Grandpa himself had jerry-rigged and driven from New Jersey to Boston and back.

[3] It was on this occasion that I first realized that if Grandpa wasn’t particularly close to any of his grandchildren, he wasn’t close to his own son, either. When the time came for Grandpa to introduce his family, he named each of us—except for UB. I then heard several voices whisper, “And your son, Griz! Your son!” –”Huh?” he said. Then I remember Gaga and my sister Kristina repeat the other voices, “Your son!”—”Oh, yeah, my son, Bruce.”