JUNE 9, 2023 – (Cont.) Two weekends later, Mother informed me that she had sold the canoe. I was astounded. Mother never got rid of anything. She didn’t buy that much, and she never, ever got rid of anything except newspapers, organic garbage, and some of the junk mail. Why on earth had she wanted to sell that canoe? It was a perfect length for her, a perfect size for any of us who might in the future want a light vessel to launch and paddle without effort. Why, oh why would she discard that canoe, which took up such precious little space way of sight, way down the hill from the cabin, in a spot so rarely seen by anyone, a little patch of ground the size of a notepad on the family’s quarter-mile stretch of undeveloped, heavily wooded, lakeside property covering 70 acres? It made no sense. It was a rare instance of spite displayed by Mother, a way for her to get back at me for the wrangling a fortnight before.

Or maybe there was more to the story.

Mother had spent much of her youth on the water. She loved water, and the more of it, the more she loved it. Before the War stole the oldest of her two Holman cousins, the one she so loved and admired, the one she talked about so often when we were growing up, the one who stood so tall and handsome, smiling so broadly and intelligently in the photograph I saw of the four of them—Bob Holman, his younger brother Bud, looking innocent then, Mother, about eight years old, laughing under her rich, dark, curly hair, and UB, standing at the end, and seeming to be in a pout—as I was saying, before the War, Mother and her favorite cousin, especially, spent a lot of time on the water up in Connecticut where their families summered. It was the last age of innocence, and together, they loved to explore the local waters—the Eight-Mile River, which led from Hamburg Cove to the Connecticut River, which, in turn, led out to Long Island Sound, just 10 miles farther south.

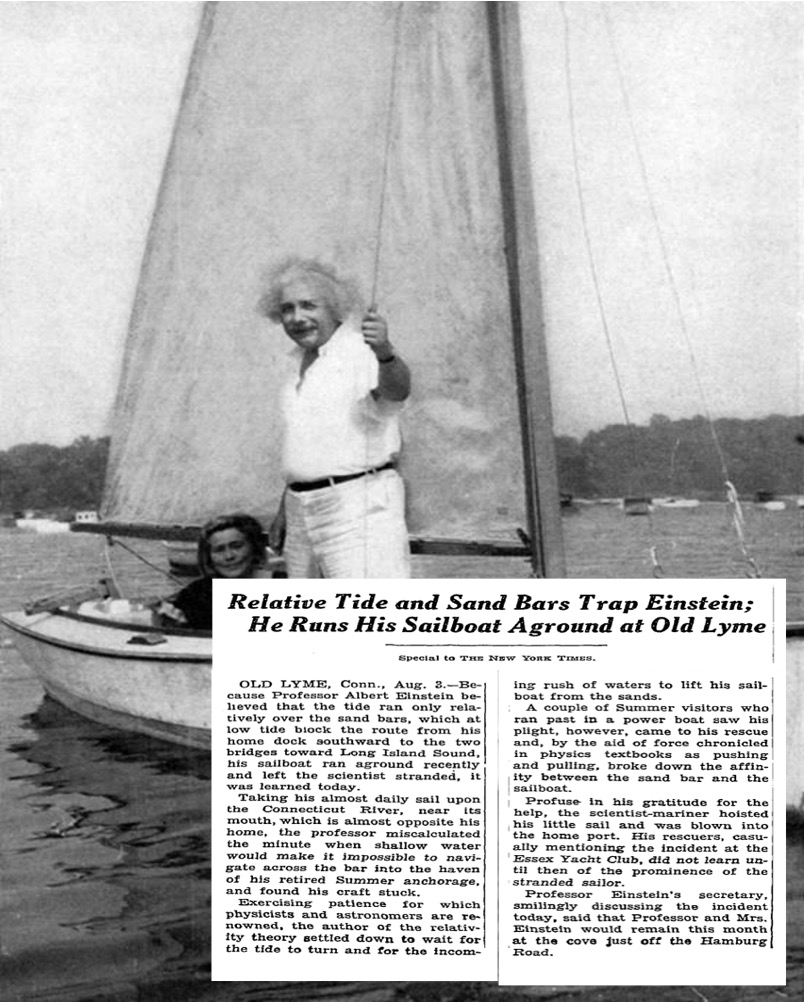

It was on one of those excursions that brought Mother and her cousin Bob Holman—there might have been others aboard, I’m not sure, because Bob was the only one whom she remembers was aboard—with a man of greatness, a man of history, a man with wild hair and a matching mustache. The man had run his boat aground on a sandbar in the middle of the Connecticut River, and seeing him stranded beside his little boat, Mother’s crew motored over to him to help him back into the current. After the rescue was complete, he asked his rescuers their names. They told him and asked his name. “Albert Einstein,” he said. The rescue effort made the front page of the New York Times, on what must have been a slow news day on August 4, 1936.

In her 60s and 70s, Mother was the only family member enthusiastic about crewing aboard my sailboat up at the lake. She hadn’t sailed since her youth, but it all came back to her quickly, and she was as cool as a seasoned sailor when things got dicey—such as on the deceptively bright summer day when we tacked into a strong breeze all the way across the lake. As we prepared to come about and shift to a reach downwind back to our side of the lake, the wind itself shifted by nearly 180 degrees. We’d now be tacking our way back. Far more ominous, however, was a blacker than coal storm front moving south directly our way.

I gulped. I didn’t want to spook Mother, so I hid my fear and silently considered our options. Mother, on the other hand, knew exactly what to do. “If we tack to port another 30 degrees, the wind will take us to Boger’s, won’t it? [The Bogers were my in-laws, who had a cabin on the west side of the lake.] We can tie up there and let the storm pass.”

“That makes sense,” I shouted defiantly into the wind and bolstered by Mother’s confidence, “if you think we can make it before the storm hits.”

“I have faith we can,” Mother said in a perfectly normal voice. I pulled the tiller to establish the proper heading as Mother adjusted the sheets. We landed at Boger’s dock less than half a minute before all hell broke loose. From the safety of my in-laws’ cabin, we waited out the squall. Mother’s calmness reminded my of Grandpa’s extraordinary unflappability—and by contrast, my limited inheritance of this admirable trait: my heart was still pounding from the storm-induced adrenaline rush.

In any event, years later when I was mired in frustration with Mother, I thought she was crazy when I learned she had sold her canoe. She did a lot of crazy things back then. But maybe she was perfectly sane when she accepted whatever cash it was that she received for her Queen Mary. Maybe her sale of the canoe was simply an ever so rare expression of the emotions otherwise absent from her—and Grandpa’s—inheritance: anger and sadness over the lost joys of life.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson