JUNE 8, 2023 – (Cont.) Down by the permanent steps that led to where the dock was supposed to be installed, I turned over Mother’s light, 13-foot aluminum canoe. It had been lying upside down there for over a year. It was tied to a tree, and the rope was doubled up so many times, I guessed it was at least thirty feet long. Tied to the other end of the canoe was another rope about five times longer than it needed to be for any probable purpose. Around one of the middle struts, Mother had attached a cable in plastic sheathing, with a clip on each end. Under the canoe, she had stored her ‘ballast’—a plastic, two-gallon K-Mart pail in which she had placed a plastic, grocery bag filled with small stones. I put the ‘ballast’ on the floor of the canoe, untied the rope from the tree and waited for Mother.

As the minutes ticked by, I gave the canoe a little shove down the two pine logs that I’d laid against the bank years ago and let gravity do the rest until the stern splashed into the water below. With one hand I then yanked the canoe back up to the top of the logs. I repeated this exercise several times as a kind of private joke.

Eventually Mother appeared, gradually descending the earthen steps that led down the hill past all the white pine spectators lining the way. She wore light blue shorts, an old sunhat, a big life jacket, and her “goggle-style” sunglasses, which made her look like a giant fly. With the straps of two seat cushions looped over her right arm, she used her left hand to navigate with one of the half dozen available canes by the back door. Her progress was drawn out but not just because of her bad hip. She proceeded slowly because she had simply gotten into the habit of walking that way, as if her gross motor movements had shifted into inverse proportion to the speed of the wheels that whirled away inside her head.

“So you’ve got it turned over,” she said as she approached. “Good. You see, Eric, I don’t want to trouble you and Beth. I know you’ve got a lot on your mind and are under a lot of stress, and I didn’t mean to sound ungrateful for all that you do for me. And you’ve got the boys to worry about, and I just pray to the Lord that everything will be okay, and your father needs my help, and I worry about his back, so you see, it’s not that I don’t understand what you’re trying to do for me.”

“Okay, Mom.” I told myself sternly to be patient and bite my tongue if I had to. “I’ll get this into the water and paddle it down to our place while you walk along the path.”

“Do you see that line?” she said, pointing the end of her cane at the mile-long rope. “That’s what I use to hold the canoe while it’s sliding down the logs there.

“Uh-huh.”

“I hold that with my left hand and then hold onto the cable with my other hand so the canoe doesn’t move too fast, and then I gently guide the canoe down the logs.”

“Uh-huh.” By this time the canoe was already in the water—for about the sixth time in the last ten minutes—by my own method.

“Did you put my ballast in?”

“Yes, it’s there.”

“Good, you see, I need that to weigh down the other end of the canoe.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Do you need help getting in?” Mother asked.

“No, I can manage. You start walking, Mother. I’ll paddle down.”

Fifteen minutes later Mother’s embarkation process began down at the Red Cabin dock. I wanted to hold the canoe to the edge of the dock and help Mother in. Instead, I had to listen to her lecture on nautical methods and procedures, starting with knots.

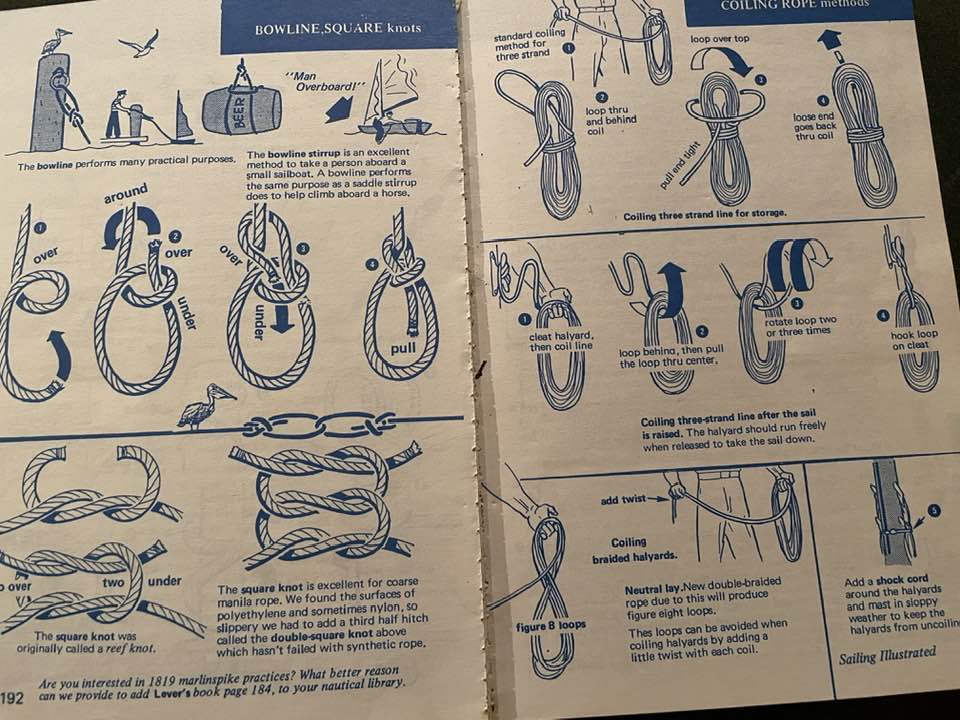

“Now there you go again, moving too fast,” she said. “I’m surprised at you, Eric, that you don’t want to follow proper procedures for handling watercraft. Didn’t you learn that the bowline should be tied to the dock?”

“Mother, you don’t need that.”

“Look, why can’t you just do as I ask?”

“Okay, okay. What do you want me to do?”

“I want you to tie that line to the dock. Can you tie a half-hitch? Do you know what a half-hitch is?”

“Mother, for crying out loud,” I said, forgetting patience, “this is a canoe, not Grandpa’s Chris-Craft.” The allusion was to the serious pleasure craft that Grandpa had once owned and enjoyed at the family’s summer getaway on Hamburg Cove back in Lyme, Connecticut.

“I have this all figured out, and there’s a proper way to do it, and I just want you to make sure the bowline is tied up properly and that you’ve got the stern line tied as well, so I can get into the canoe.”

“It’s a canoe!” I said.

“I know that, but please, just listen to me.”

Mother now had one cushion on the seat at the back of the canoe and the other on the dock. She sat down on the dock cushion and with her cane, drew the canoe close up to the dock. “Now, what I have to do is make sure that the canoe is right snug up against the dock, so that when I move . . . When I move from here to the seat, is that line going to be all right? You see, I have to make sure there’s enough line to let the canoe out but not too far. Can you check it?”

“What do you want me to check?”

“The line back there. Is that a half-hitch?”

“Yes, it’s a half-hitch, Mother. “Now, do you want me to help you in?”

“No, I just want you to watch to make sure I’m doing the right thing.” She swung her feet into the canoe and held her calves against the gunwale. “There,” she said. “Now, can you put the ballast up a little farther there?” She pointed with her cane.

It took another five minutes for her to get herself situated properly before I was allowed to release the ropes. Sorry, the “lines.” She dipped the paddle into the lake and moved the canoe away from the dock. I watched for a minute or two, as she cut a lazy circle through the placid water a few yards out from the end of the dock. I then walked back onto shore and repaired to the cedar swing to watch Mother at sea.

Not more than 10 minutes later she returned to port. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson