JUNE 6, 2023 – (Cont.) On rainy, boring, summer days when I was a kid and after exhausting other entertainment options, I’d rummage through the drawers of the tall secretary in the living room to see if there was anything I’d missed on previous expeditions. There were the rubber stamps, the magnifying glass, the cute little books that had handwriting on every page, a small rubber ball, a blue and yellow box with fountain pen refills, a clipping from the front page of the Anoka County Union, featuring a large photo of what was then our entire family (my sister Jenny not having yet arrived) under the headline, NILSSON APPOINTED CLERK OF COURT, and the shallow green can containing a couple of three-cent ‘Liberty’ postage stamps, a rubber band and paper clips. And there was the slide rule.

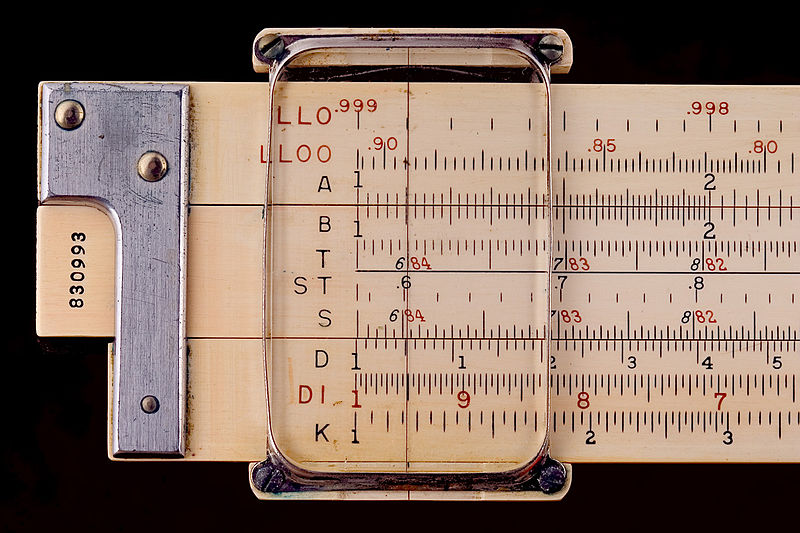

I was thoroughly mystified by the slide rule. On each journey through the drawers of the secretary, I’d remove the slide rule from its heavy leather case and carefully move the parts back and forth. I liked the way it felt and all the numbers and lines and pi, though at the time, of course, I didn’t know it was pi. I didn’t think the slide rule could be a toy, because it appeared way too serious a thing to be a toy. Each time I asked Mother what it was, she didn’t seem much interested and just mumbled some words I didn’t understand, and I’d put the device carefully back in the case, return it to the drawer and continue on my way.

By the time I was in my early teens, I occasionally overheard Mother in conversation with Dad or friends mention “Syracuse” and “Rensselaer,” and I began to notice now and again an item in the mail that would bear one or the other of those names. However, it wasn’t until I began to investigate colleges for myself that I asked Mother, “So, Mom, exactly where did you go to college?”

“I went to Syracuse, because it was a fine school, and I’d had a friend go there and your grandpa thought it would be a very good place for me, so there I went. But then the war came, and the country needed engineers, so I decided to go through the program at RPI.”

“RPI?” I asked. “What was that?”

“Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York,” she said. “Because all the men, or most of them, anyway, had gone off to war, they really needed women who were good at math to take their places, so we—there were a lot of us—we worked without a break to complete a four-year course in just nine months. We ate together, slept together, studied together and became very close, but it was very stressful. There was never any down time. We were working all the time when we weren’t sleeping or eating.[1]”

A short time later, I thumbed through a college handbook, which listed every college and university you’ve heard of and every one you haven’t. Under each institution name was some basic information, including average SAT/ACT scores for accepted applicants from the previous year. I checked RPI and found that for math, the average score was 790 (out of a possible 800), equal to MIT and higher than any Ivy League school. It was at that moment that my respect for Mother’s intellect made a quantum leap.

I asked her again about the slide rule in the leather case, and this time, she gave me a demonstration. She amazed me by the speed with which she worked the device. She ran calculations nearly as fast as I could on the Texas Instrument calculators that were then becoming more accessible to high school math students.[2] (Cont.)

[1] Much later I learned that Mother was a member of an elite engineering cadre called the “Curtiss-Wright Cadettes,” a group of 918 women graduates of a Curtiss-Wright sponsored program with the top seven aeronautical engineering schools in the country. A few years before Mother’s death, I was contacted by Jean Vi Lenthe, daughter of one of the Cadettes. She had published a book, Flying into Yesterday: My Search for the Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical Engineering Cadettes (2011), which described in fascinating detail the mission and accomplishments of these largely unsung heroines of the American WW II effort. Ms. Lenthe was working on an updated version of the book and wanted to interview Mother. Mother was less than enthusiastic about it. She possessed no desire to massage her ego, feed nostalgia, retreat into sentimentality, or satisfy people’s curiosity about her.

[2] Decades later, after Dad died and we’d moved Mother into an assisted living facility, I found in my parents’ full-story attic a heavy box of declassified work papers on which Mother had written a bazillion slide rule calculations. They represented her contribution to the war effort—the mathematical stress analysis of the design for the propeller of the P-51 – Mustang.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson