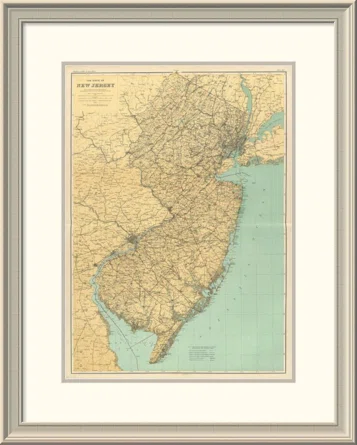

JULY 28, 2023 – When I was a little boy, there was a large, framed map on my bedroom wall. Mother told me it was of New Jersey, but she also told me that her home state was much older than Minnesota, so why it was called “New” and not “Old Jersey” was a mystery to me. The map itself looked quite old, and it had little amusing icons and characters on it, as if it had been designed especially for kids my age. During nap times, I used to lie in bed and survey every detail of the map, coursing counterclockwise along every little bend of the boundary until my eyes reached the flat part along the New York border (though at the time, I didn’t know it was New York), where I wondered why that part was perfectly flat and the rest of the boundary wasn’t and then coursing around again—over and over. Every three or four times around, I’d look at the figure in the upper right hand corner—a funny little man wearing a dark, old-fashioned hat, a sinister looking cape and shoes with big buckles. He was peering down, with his arms stretched straight out and his hands in little white gloves pointing down toward the bottom of the map. I didn’t know what he was doing there, and I thought he was up to no good, and it bothered me. Only when I was 50 and found the map tucked away in a corner of my parents’ spacious attic did I see that the little man—a Colonial, no doubt—with his outstretched arms, was not sinister at all but had been serving tirelessly all those years as the distance scale.

Anyway, thanks to the map—and I now freely admit, those nap times imposed by Mother—I became intimately familiar with the shape of New Jersey. It would take some time before I would know the names, the shapes, the relative sizes of the states that separated Mother’s home state from Minnesota.

My first trip to New Jersey came when I was nearly three. I know that was my age then, because it was in the summer; my birthday is in August; Mother’s stomach was big; and my sister Jenny, three years younger than I, was born in September.

We traveled by train—Mother, Nina, Elsa, and I. The first train of our two-train journey had cars with glass ceilings that curved part way down the walls, and there was lots of light[1]. Beyond that, I don’t remember much about the ride from Minneapolis to Chicago, except that it took all day. The next train, from Chicago to New Jersey looked totally different. It was a dark, off-putting burgundy on the outside, contrasting with the more pleasing two-tone green of the first train. Whereas the diesel locomotive of the first train, with its two forward windows over the light looked like two eyes over a nose, giving it personality, the massive reversible electric engines of the Pennsylvania Railroad had windows on the sides and seemed sinister to me[2]. The Chicago-New Jersey train didn’t have any dome observation cars, either. Mother told me that we would be sleeping on this second train, and I figured that since we would be sleeping, there would be nothing to look at anyway.

I don’t remember a lot about the second train ride either, but three things stood out. First was the dining car. It was there where I saw a black man up close for the first time. He served us dinner, so he got close enough to touch, and I wondered why his skin had gotten so dark. It was made all the darker by his white coat and the white linens. More than the train ride itself, this black man revealed to me that the world was a much bigger, different place from what I had assumed.

The second thing I remember was our sleeping compartment, the full-length mirror on the inside of the door, and the power of suggestion in Mother’s admonition. I’m not sure of the exact arrangement, but one of the berths seemed to stretch out beside the window opposite the door. Once it grew dark and Mother had decided it was time for us all to go to sleep, she accommodated me with her on the window berth. After dozing off initially, I later must have had trouble sleeping, since Mother warned me that if I didn’t lie still, the conductor would come by and see to it that I did. Her words worked a strange effect on my imagination, because I remember that after she herself had dozed off, I kept sitting up in the berth and peering at the mirror. In the shadows, I could see the dim outline of my own image, only I didn’t see my own image. The mirror had turned into a window out into the corridor of the Pullman car, and in the window, I saw the conductor, staring at me, ready to impose discipline if I didn’t go back to sleep. I lay back down but with my eyes wide open, and I wondered how long I would have to lie there before the conductor would move on to check on other kids that were aboard the train. After a time, I sat up again, but there he was, still standing in front of the “window.” I must have repeated this exercise a number of times, never developing any particular fear of the conductor, just admiration that he seemed to have as much patience as necessary to see to it that I would eventually drift off to sleep.

The third thing that I remember about the Chicago-New Jersey train was “Horseshoe Curve[3]” very late into the night. I was sound asleep by the time that we approached it, and I remember waking to a sizable commotion inside our sleeper, as Mother moved about on the berth to peer out the window and in a loud whisper, woke my two older sisters to alert them to the approach of this notable section of the trip. She explained that this was where there was such a long, sharp curve in the track, you could see both the front and the rear of the train from a middle car, which is where our sleeper happened to be. I sat up too, pressed my nose to the glass under Mother’s chin and strained to see what she was talking about. Sure enough. In one direction, I could see the sinister locomotives and the opposite way, I could see lights through the windows of the tail-end car. It seemed to be a kind of magic trick, and I wondered how and why the grown-ups in charge of the train would pull such a thing so late at night when most people were asleep.

* * *

It’s interesting what memories form and stick with you when you’re a very young kid. Surely the important stuff—a parent’s hug, a parent’s warning, a sibling’s taunt or helping hand—forms an impression, which mixes with a whole lot of others to mold your outlook, form your personality, and direct your idiosyncrasies. But distinct memories are quite another matter. Except perhaps the particularly traumatic experiences (in my own case, chomping on glass Christmas tree ornaments and winding up in the hospital when I was only 14 months old, or swallowing an ice cube when I was three and being certain for the next ten minutes that I was going to die as a result), early memories seem to be totally random, unrelated to their significance in the overall scheme of things. So it was with my memories of that first trip to “Old” Jersey.

I don’t know how long we stayed. Given the effort required to get there and back, I’m sure it was a minimum of two weeks, but it could just as easily have been a month. In whatever time it was, several impressions formed.

The first was of Gaga and Grandpa. They welcomed us warmly, but my frame of reference was my Nilsson grandparents back in Minnesota, whom we saw on a regular basis. Ga was very reserved and refined. Gaga was more outspoken and her hard New Jersey accent, wholly alien to me, contrasted greatly with Ga’s soft, Swedish lilt. Grandpa Holman wore a suit all the time, and likewise, I compared him with Grandpa Nilsson, who was retired, and except for special occasions, never wore a suit but more comfortable looking clothes. And whereas Grandpa Nilsson worked on projects around his house or sat in a chair, reading a book or working what I later learned were crossword puzzles or went for a long walk with Dad, Grandpa Holman was gone most of the time, over in the offices, I was told, that occupied the ground floor of the warehouse complex across the broad driveway behind the house.

The house itself—42 Lincoln Avenue[4]—was a regular castle on my scale of things. Much larger than our house back in Anoka, it had many secret doors, corners, rooms and spaces. It had several stairways, even a secret one (for servants, I later learned) where a person would be “invisible,” according to Gaga. Each room seemed to have a rich, dark carpet, and even in the eyes of a three-year old, the furniture looked much darker and more important than what I was accustomed to in our own house—though as I would learn years later, much of our furniture and had been fully subsidized by Gaga and Grandpa. Even Grandpa’s car was more important. It had four doors instead of two, and in place of cranks for rolling windows up and down, it had little buttons, which if you touched, made the windows open and close like magic.

More specifically, I remember riding with everyone—Gaga, Uncle Bruce, Mother, Nina and Elsa (Grandpa being hard at work back at the business office)—in Uncle Bruce’s blue convertible with the top down and big fins with chrome on the backside[5]. I sat squeezed in the back with Mother and my sisters and I watched Gaga’s neck scarf blew straight back over the front seat when we drove fast. Our destination turned out to be the home where Gaga’s mother, Orrell Baldwin, lived, some distance from 42 Lincoln. About my great-grandmother, I remember very little, except that she lived in a little room and wore glasses. Gaga wore glasses, and since she, Grandpa, and Gaga’s mother were the only three people in the family who wore glasses, I figured that they were more closely related to one another than to the rest of us, except that once in awhile Uncle Bruce would wear glasses too, which made sense, because he was Gaga and Grandpa’s son and lived with them, and Mother didn’t wear glasses, because even though Gaga and Grandpa were her parents too, she no longer lived with them.

Another thing that I remember about that first trip to 42 Lincoln was the toy trucks that I got to play with on the back steps of the house. They were promotional toys for United Van Lines, sporting the original font and color scheme of red, black and beige[6], just a few years before a new logo and colors were introduced. I noticed that they were miniatures of the trucks that came in and out of the driveway all day—the driveway that led to the gigantic garage behind a big, old wooden building, which, as I later learned, was part of the original collection of warehouses built before the end of the 19th Century by Grandpa’s father, George B. Holman.

There was also a summer evening when Grandpa drove Gaga, Mother, my sisters and me down to the Meadowlands, where Grandpa had bought land for a trucking facility. There were wild blackberries in abundance there, and I remember how everyone went about the bushes picking berries. I also remember that Grandpa was not wearing his suit, and I thought that meant that he could be more like my other grandpa than I had assumed, though I wondered why he wasn’t more like my other grandpa all the time.

Then there was the time when I had a nightmare, and I was scared, so Mother and Gaga tried to calm me down. I remember the actual dream. It was a recurring one about snakes in my bed. Large, dark, striped, ominous creatures, slithering around, scaring the bejesus out of me. I woke up, crying, calling out for Mother, and she lifted me out of the bed (I think it was a crib of some sort) and brought me out into the light of the large landing from which you could enter any of the rooms on the second floor. Mother and Gaga kept telling me, “It was only a dream,” but they didn’t seem to understand that the dream was inside my bed. I’m not sure how it was that I got back to sleep, unless it was from the sheer exhaustion of crying.

There was another ominous event during that first trip to New Jersey, but I did not learn of it until I was decades older. Nina told me that one night after I had been put to bed, Grandpa arrived home late from some kind of meeting. Quite a commotion erupted among the grown-ups—Gaga, Uncle Bruce, and Mother—over his appearance. “He had blood all over his shirt,” said Nina. “They immediately rushed me away, but I heard talk about a knife and ‘Teamsters,’ but the whole thing was hush-hush, and I was too young to know what was going on.”

Years later, I would learn that Grandpa ran a non-union shop, and putting that fact together with Nina’s report, suggests that Grandpa was a target of the infamously corrupt Teamsters union, but after all, we were talking New Jersey[7]. I have no doubt that Grandpa would have resisted any pressure, irrespective of the threats. He was fearless. I would have opportunities to see just how fearless, but it would be another 20 years or so.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[7] During Prohibition, the local G-men contracted with Geo. B. Holman & Co., Inc. to remove and warehouse illicit distilleries and inventories. Grandpa once told me that he’d get calls at all hours of the night just ahead of planned raids on illegal operations so that he could have trucks and drivers ready to pick up and remove all the evidence—including barrels of hard liquor. Grandpa was the right man for the job: he was a teetotaler and absolutely incorruptible.