SEPTEMBER 16, 2023 – If I’d wanted to stay clear of New Jersey, New Jersey didn’t want to stay clear of me. Or more precisely, Cliff wouldn’t let me bury my head in the sand. Less than two weeks after my return to Minnesota, he called to sound the alarm—yet again—about the money stream going to Alex.

“I’ve been swamped lately,” said Cliff “absolutely swamped, but I had to let you know that there’s just no stopping ’im—no stopping Uncle Bruce from sending wheelbarrows of cash to our Serbian asshole friend in London.

“Eric, there’s got to be something we can do. I mean, why aren’t we talking to the FBI or Scotland Yard or Jesus Christ, why aren’t you and I—aside from the fact we’re busier than ever—but why aren’t you and I on the next plane to London to track down that slimy drug addict and scare the living shit out of him so that he disappears from Uncle Bruce’s life once and for all? I mean, you’re a lawyer, for god’s sake. Can’t you figure out how we can stop this? It’s wrong, Eric. It’s so wrong I can’t stand it.”

We’d been over the same territory numerous times. Cliff gave the same speech almost every time the subject of newfound Western Union receipts came up. The only variation to his tirade was the choice of uncomplimentary epithets. To each repeat of the rant I’d given the same response: yes it was wrong, yes it was terrible, but no one in the family, and certainly not I, could countenance spending thousands—probably 10s of thousands on legal fees—to extract a remedy from the slow-grinding wheels of justice.

The problem wasn’t UB’s insanity but his sanity. If evidence of his OCD behaviors, his garbage house, his inability to observe basic hygiene practices were sufficient to blow the mind of a judge, UB could mount a rigorous defense. I knew how it would be spun: it’s a free country where a person can live like a skunk and be quirky as can be; where no one has the right to tell another how often his toilet bowl should be cleaned, how many clocks or thermometers in a room of his house are too many or how many dozens of gay porn tapes are excessive. Moe to the point, “Exhibit A” in UB’s opposition to a guardianship petition would be his medication matrix that I’d seen on the kitchen wall showing an “X” next to every one of his numerous meds at every prescribed time for the past month—except for the morning after the blow-up with me.

A conservatorship—a court appointed and court supervised regime imposing control over UB’s finances—would be an even steeper slope to climb. Two witnesses would knock us off the mountain: UB himself and UB’s stock broker. “Does he pay like clockwork the quarterly real estate tax bills due on multiple parcels? Does he pay all his other bills on time?” Yes and yes. Only a person with extreme OCD would write on each utility bill, the check date and number, then make five copies and enter the information on three different sheets of accounting paper, each entitled, “Monthly Cash Journal.” So what if his filing system was an electric fan? I could name many old school lawyers still in full command of their faculties who used the same organizing method.

And most impressive, like a finance/investment savant, UB could talk anyone’s head off when it came to stocks, bonds, ETFs, mutual funds, portfolio balancing, P/E ratios, debt service coverage ratios, interest rate swap agreements . . . and the like. All his lawyer would have to do would be to put UB on the stand and emulate the scene in My Cousin Vinny (1992), when Vinny Gambini (Joe Pesci) unleashes his gear-head fiancé, Mona Lisa Vito (Marisa Tomei), as an expert witness to testify on the make and model of the getaway car in a murder case. Just as Ms. Vito destroyed the prosecution’s case, UB would do the same against any claim that he was financially incompetent.

Moreover, when it came to the central purpose of a conservatorship—ending the free-flow of funds to London—we faced two more fundamental problems.

First, because UB’s papers where in such chaos; because we couldn’t establish his full financial picture, we couldn’t know whether he was in danger of depleting his resources or the opposite—that he had more money to burn than even Alex could dream was available. Some rich people pay $100,000 on a new car every year. What’s the difference between that case of self-indulgence and sending $100,000 a year to a “close friend”[1]? And without a rigorous accounting, we couldn’t know what portion of Mother’s inheritance had been sailing one-way across the Atlantic. Thus, we’d have to combine a conservatorship petition with a companion case seeking an accounting and replacement of UB as executor of my grandparents’ estates and trustee of their trusts. The resultant litigation could go on for years.

Second, there were the tapes. After listening to many hours of conversations between donor and donee, giver and taker, “victim” and “perpetrator,” I reached the inconvenient conclusion that the relationship between UB and Alex was more complicated, less definitive than a typical scam targeting a vulnerable senior citizen. An exchange would go something like this:

[Following UB’s announcement of time and date]

“Hallo.”

“We’re here.”

“George, I told you not to call me anymore.”

“You’re not feeling well today? Have you had enough to eat?”

“No George. I don’t want to talk to you.”

“When did you last eat?”

“George, I told you, I don’t want to talk to you any more. Don’t call me.”

“But you need help.”

“No I don’t George.”

“Yes you do. Isn’t your rent almost due?”

“Yes, George, but I don’t need your help. Katrina said she’d help me.”

“She doesn’t need to help you. You’ve got me.”

“Okay, okay, George. If you inthitht on helping me . . . but George thith ith the latht time. I don’t want you calling me anymore.”

“How much do you need?”

“Three thouthand poundth.”

“Three thousand pounds? But we sent you 2,000 just last week.”

“I know, George, but you thaid you wanted to help me.”

“Okay. The bank isn’t open yet and we have to get dressed and have something to eat. But we can get the money out in about an hour. Will that work?”

“Yeth, George.”

What I drew from these calls was that the relationship was a two-way street. On the one hand, UB was absolutely infatuated with Alex: the vast majority of conversations were initiated by UB, and despite Alex not feeling well, not having time, not wanting to talk, UB insisted on badgering Alex with questions and engaging him in conversation. On the other hand, knowing full well that the lonely psychologically vulnerable 84-year old American was head over heels in love with him, Alex “played him like a fiddle,” to borrow Jeanette’s initial assessment of the Serbian back when Cliff and I were so certain we’d chased Alex out of the picture. In any event, it was hardly a case of “theft by swindle.” It was more an instance of leveraging infatuation.

Aside from exhaustive analyses of law and facts, however, UB—and Alex—held the ultimate ace in the hole: UB’s sole and unfettered ownership of the Connecticut property, putting it completely outside the orbit of Mother’s inheritance. In contemptuous retaliation against any legal remedies that might be initiated against him, UB could gift—or threaten to convey—Hamburg to the Serbian. Sure, we could seek legal remedies against that catastrophe, but if I’d learned anything in my years of practicing law, it was these two maxims:

The proverbial “open and shut” case is as rare as a two-headed unicorn.

and

In percentage terms, litigation cost overruns will inevitably exceed the worst of rogue kitchen remodeling projects.

Despite my description of reality, Cliff refused to believe there was “nothing we could do.” As sure as I was of my analysis, I feared Cliff’s loss of confidence in my character. I told him I’d “think of something.”

“Good,” he said, letting me off the hook . . . for now.

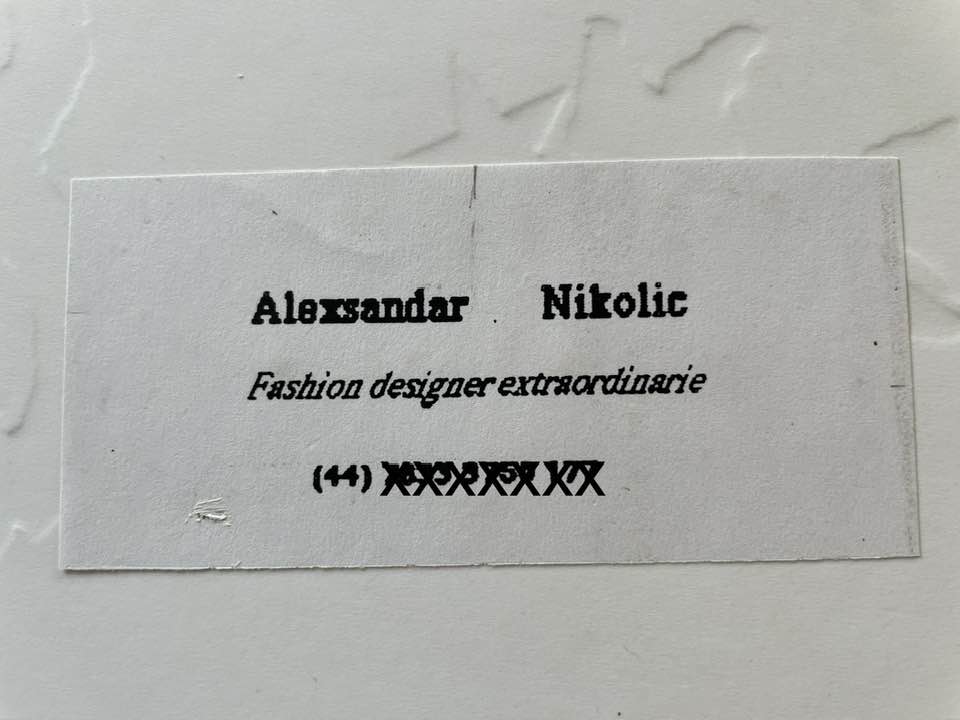

The “something” turned out to be a letter from me to Alex. I felt good writing it; even better revising it; better still reading my final draft and signing it; and fully triumphant when handing the envelope—with extra postage—to the postal clerk.

In fact the letter was worse than ingloriously ineffective: like most acts of vengeance, it backfired.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] This was the approximate run-rate after the spigot was opened in early 2004.