OCTOBER 18, 2023 – Joining us on our memorial mission were Byron along with Cliff’s neighbor Steve—a retired bank examiner and avid downhill skier. Our late start was from Rutherford the Friday evening of Presidents’ Day Weekend. We’d first had to wait for Byron to leave work in the city and cross over the Hudson; then for the four of us to chow down at the Blarney Station Pub just over the tracks in East Rutherford.

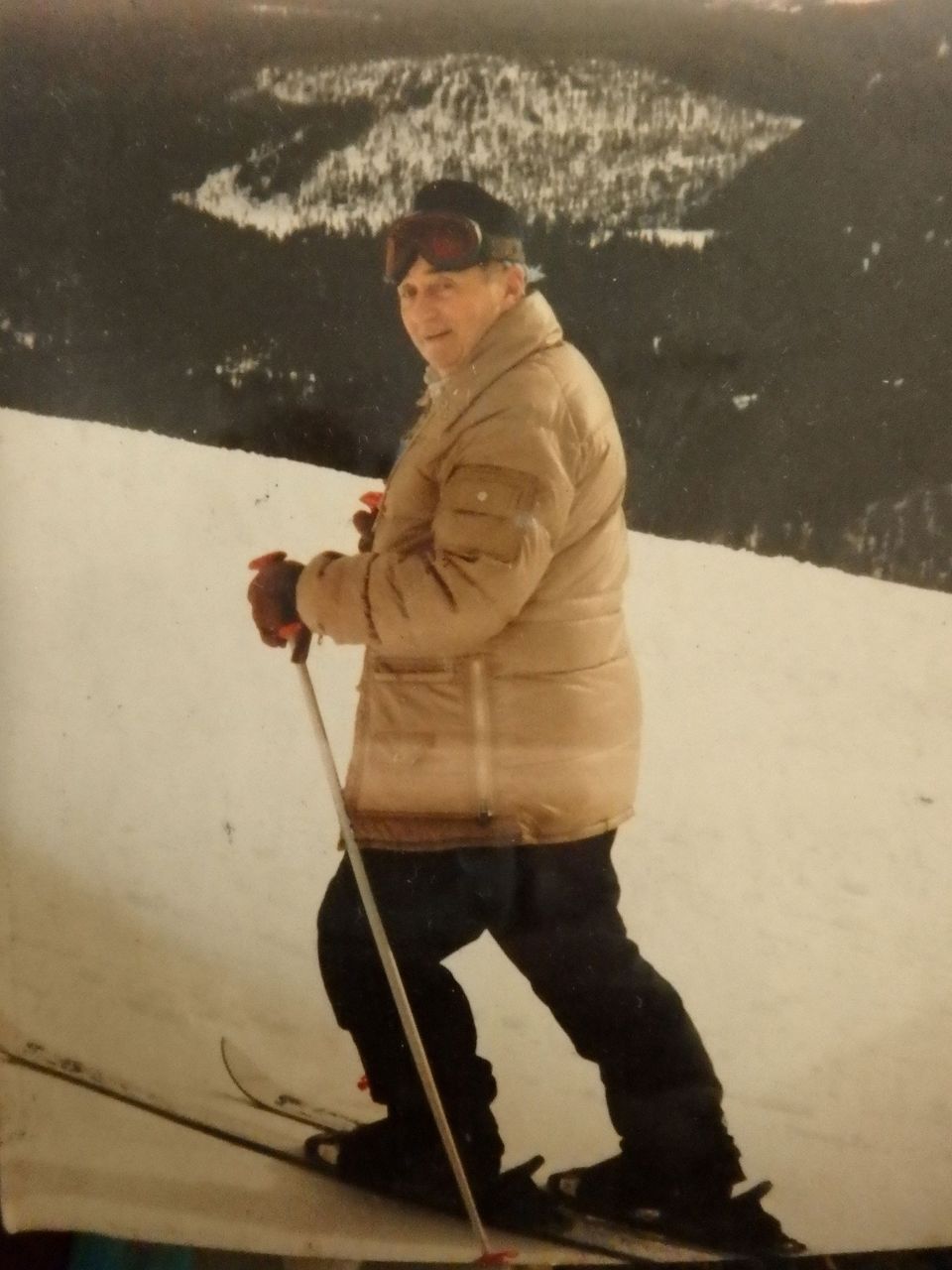

Once underway, Cliff drove as usual like a NASCAR competitor. The mild-mannered Steve entertained us with his crooner play lists through the Denali sound system. Also a big crooner fan, Byron formed an immediate rapport with Steve, but then again, Byron is a master of the art of conversation. I was grateful that he’d made the effort to join our mission. As he’d gained experience in the world of banking and business, Byron had become my confidant in all matters relating to the disposition of the Rutherford properties, and in the process he’d become well acquainted with Cliff. I was immensely pleased that the two of them had developed a genuine respect for each other. It didn’t hurt that they were both big sports fans and liked to downhill ski.

By the time we reached our lodging in Brattleboro, I had nearly become a Born-Again believer given that the Denali and its four occupants had survived the maniacal drive. From a practical standpoint, however, Cliff’s quick reflexes and time-distance perception compensated for his compulsion to beat all other vehicles traveling north on the New York Throughway and those moving east on Route 9 across Vermont. (On the return trip the following Monday, Cliff handed the Denali keys off to Byron. I viewed the gesture as a badge of honor, confidence, and prudence conferred upon Byron. I also knew it was Cliff’s way to tweak me for having asked him (in vain) to back off from 90 miles an hour on our drive north Friday evening.)

For the next three days, we skied Mount Snow among a diverse crowd, with New York and New Jersey well represented. Cliff was nursing a chronically sore knee and Steve was a two-time heart attack survivor, so in a bit of an ironic role reversal, the two of them took a backseat to the more aggressive approach that Byron and I pursued down the North Face of the mountain. Conditions were superb, and the two of us skied as if we owned the place.

Over dinner Saturday evening and again Sunday, we ate like kings and talked like free-range commentators until nearly all the other patrons had departed. We then repaired to our motel, where we collapsed into deep long sleep.

On Monday afternoon, we finally got to our main mission. If the dispersal of ashes in Hamburg the previous August had been my sisters’ final good-bye to UB (and Mother), Cliff and I had a follow-up ceremony to undertake: spreading the third and final portion of UB’s ashes across the snows of Hogback Mountain.

The former ski area of which UB was an active owner had been abandoned 33 years before, and in evidence of nature’s resilience, trees had reconquered the wide open slopes. The original roadside chalet, however, remained. It was where UB had fraternized so exuberantly with the Whites and the Hamiltons, who managed the successful little resort, and on my many ski trips there with UB, I’d formed my own fond memories of the place and its people. Recollections filled my thoughts as I put my nose to the plate glass of the vacant chalet and cupped my face to allow a view of the interior. Among the crowd of skiers sipping hot chocolate fortitude for a return to the slopes, I could see UB in his signature light green ski hat—more of a beanie, it seemed—with the tassel that swung like a metronome’s pendulum to his perfectly executed turns. I could also see him laugh in banter with the jolly Arnold White in his signature dark green Alpine cap bedecked with a dozen ski pins that sparkled in the reclining sunlight. I saw UB sharing ideas with Erik Hammerlund, my private instructor and the finest skier I’d ever know. I saw UB’s wide smile as we stole glances on our descents down the slopes of Hogback. Filling the inner ring of recall was “the man who invented skiing”—free of the baggage, the burdens of mental disorders that had so bedeviled his later years.

Cliff and I then faced what had been the main slope leading down to the chalet. “That’s where we want to go,” I told Cliff. “Up among those trees on the ridge up there. It was from that spot that we’d always take our last run of the day.”

“Whatever you say, we’ll do,” said Cliff. “Byron? You going with us?” Steve had already turned back toward the car. I could see from Byron’s stance that he was more inclined to follow the crooner fan than the sentimentalists.

“No, that’s okay,” Byron said. “I’ll stay back with Steve.”

I was a bit disappointed, but I understood. Byron had had very limited interaction with UB. The closest Byron had gotten to him was in the stage seating at a performance of A Prairie Home Companion at the Fitzgerald Theater in downtown St. Paul. The occasion was on the same evening when Cory, Cliff, UB and I would later take Amtrak’s The Empire Builder for our ski trip to Montana. While we skiers returned to our house to make last minute preparations for the 11:00 departure, six-and-a-half-year-old Byron joined Garrison’s after-show dinner with none other than George McGovern, the war hero, esteemed senator emeritus from South Dakota and 1972 Democratic candidate for president[1].

In any event, as our patient ski companions waited in the Denali, Cliff and I trudged through deep snow toward our objective. The small bag of UB’s ashes was secure inside the zipped pocket of my ski parka.

Upon reaching our destination, I surveyed the distant horizon, the “100-mile view,” as it was described on the placemats at the Skyline Restaurant across the highway, where UB and I enjoyed a hearty breakfast—bacon, eggs, and toast for him; the “golden waffle with real Vermont maple syrup, blueberry syrup, and mouth-watering drawn butter” for me—before each day on the slopes. As is the case with so many times in memory, those were the halcyon days, when UB and I skied for days on end during innumerable school vacations. Days when I was an incorrigible dreamer and UB was a good deal younger than I was as I then stood ruminating in knee-deep snow.

“Where do you think we should leave UB?” Cliff said, interrupting my thoughts. I saw that his tracks had diverged from mine to a point 20 feet away.

“How about up on that little knoll?” I pointed to a prominent bulge under winter’s blanket.

As it turned out, the snow got deeper on my side. I traversed toward Cliff but soon got bogged down farther. “Wait,” I said. “My boots are full of snow. Come down a bit, and I’ll hand you the ashes.”

“You got it.” Cliff retraced his deep footsteps to where I could hand him the last remains of UB. As I watched, Cliff then turned and forged ahead to the knoll. With the same patience that leavened his non-stop energy through the long course of living in “the world according to Bruce,” Cliff opened the bag of ashes and gently encouraged their escape over the abandoned ski run. It was fully befitting, I thought, that Cliff, my honorary cousin by way of his improbable role in the life of UB, would be the one to disperse the third and final set of UB’s ashes.

We watched in silence as a current of air teased the ashes from the bag and out across the snow. In another month the snows would melt, the maple sap would run, and the last of UB would mix with the good earth of Hogback Mountain, Vermont, a place he loved as much as his inheritors would love Hamburg Cove, where the Vermont snowmelt would pass on its way to the sea.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] When Beth later asked Byron if he realized exactly who Garrison’s friend was, Byron answered, “Yeah, some government guy.” Apparently during the long, steak dinner (the highlight of the occasion for the first-grader), Byron had picked up the “govern” part of “McGovern.”