JULY 11, 2023 – (Cont.) Grandpa died at 92. He’d been ailing for four years after he failed to negotiate an unusually high curb on his way to the post office on the other side of Lincoln Park in Rutherford. He fell and struck his head on the pavement. Grandpa fought back valiantly, but he was never the same, and his long, hard-working life finally came to an end.

I did not attend his funeral. On the day he died, I was on a ski trip out in Utah. I could have made it back East to join the rest of the family, but I didn’t. By that time I was unable to get past the disillusionment when a few years earlier I had seen Grandpa immersed in “paprwrk, paprwrk” and obsessed with control. Old age had rendered him incompetent, but he refused to let go. The result was an irreversible decline of . . . my inheritance, at least as I had then defined it.

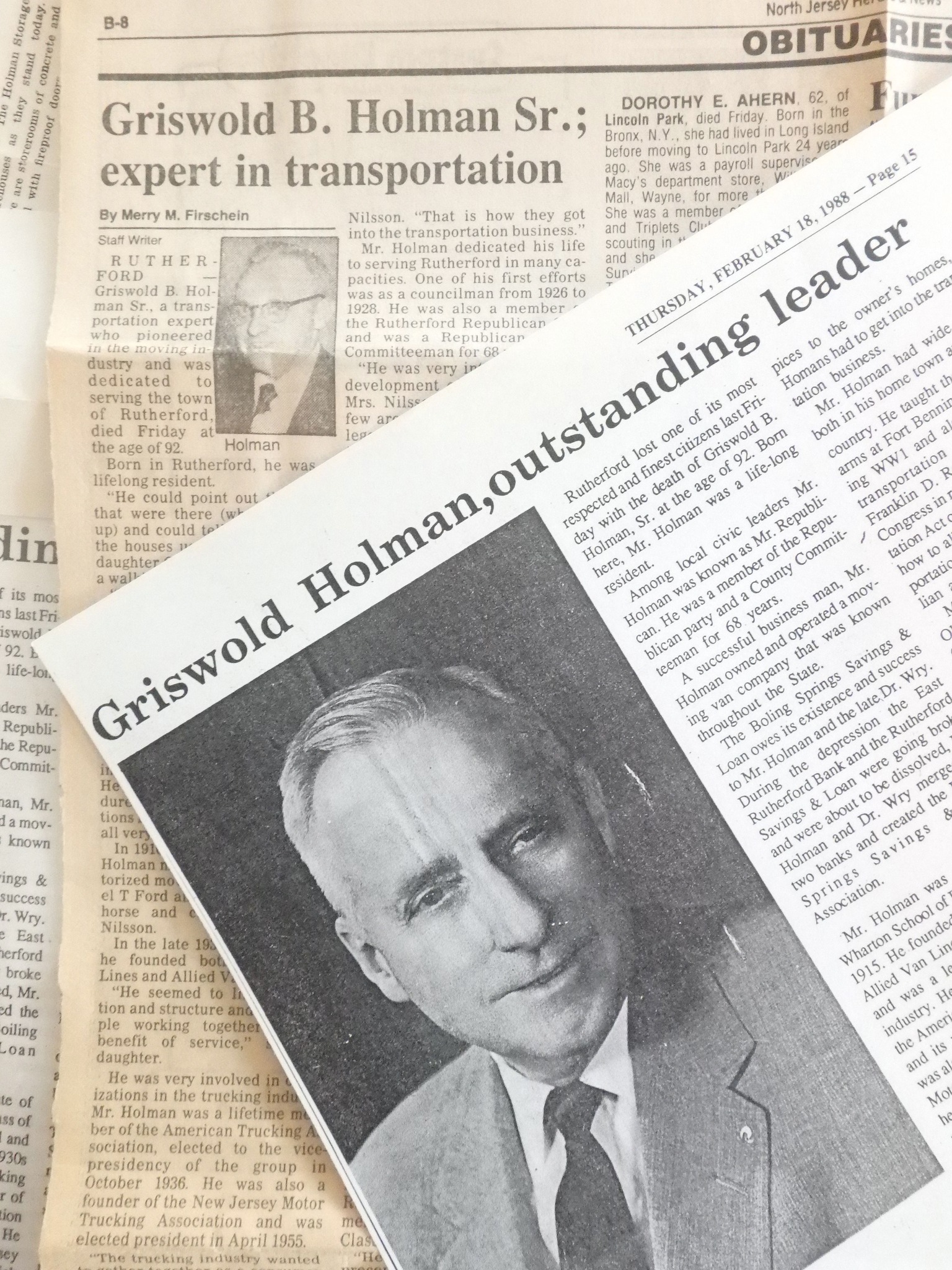

With time, of course, I would regret my decision, as I would regret my failure to pay my respects at his gravesite each time I visited Rutherford after Grandpa’s death in February 1988. Knowing now what I know about the family, mostly UB, my regret is not based on guilt. It’s based on my inability at the time—and for a good many years thereafter—to see, understand and appreciate my true and lasting inheritance.

There are two things about Grandpa’s funeral that I remember having been recounted to me by my sisters—all three of whom did attend the service. First was a note that UB had written and had placed on an easel standing next to the coffin. Elsa told me it was one of the most touching expressions of affection that she had ever seen or heard from UB. Second was what was described—by Elsa, again—an outpouring of inconsolable grief on UB’s part. Someone once remarked to me that the people who grieve the most over another’s death are those who were not reconciled to the decedent. I think maybe that was what accounted for UB’s reported “total breakdown.”

He and Grandpa had not seen eye-to-eye on much of anything, and as far as I could observe, they expressed no affinity for each other. As far back as I could remember and in my presence, anyway, their exchanges were limited to UB talking “short” to Grandpa and Grandpa talking in only short phrases—and strictly about bihness—to UB. This strained relationship was not a distant one: Grandpa and UB lived under the same roof for Grandpa’s entire life after UB was born, except UB’s college and army years and during his travels and ski trips. Based on what Mother and Gaga told me, Grandpa was probably no more fatherly toward UB than Grandpa was grandfatherly toward my sisters and me. Mother mentioned to me too that UB had been exceptionally sickly as a boy and coddled by Gaga. If Grandpa was generally incapable of displaying affection, he probably had no clue as to how to bond with UB.

But many years after Grandpa had died, as UB and I were moving around some old United Van Lines papers, he began telling me about Grandpa’s efforts and contributions to the formation of the moving company. UB spoke not only respectfully but admiringly, even glowingly, and I realized that on some level, UB held Grandpa in high regard. Perhaps it was symbolic of UB’s deep-down respect for Grandpa that he, UB, left the eyeglasses on the bust of Grandpa . . .

. . . Most people in our era have or have seen a photograph of their maternal grandfather. Few families, however, possess a sculpted bust of the man—complete with real eyeglasses.

For years, Grandpa leased space to a local sculptor with remarkable skill and talent if not renown—one Jerome Gordon. “Jerry,” as he insisted we call him, was very kind, generous, cheerful, respectful and friendly toward everyone. He lived in a wealthy area of Bergen County, and by the time we knew him, Jerry was definitely working for pleasure, not lucre. He was probably in his late 60s when I was employed by Holman Inc., and my daily encounters with him were a breath of fresh air in the stultifying atmosphere of the old warehouses. Sunshine always managed to fill his interesting studio, and I much admired the work that filled his workspace, particularly in light of the fact that Jerry’s large hands exhibited a rather severe tremor.

He loved to banter—or try to banter—with Grandpa, whom Jerry always addressed and referred to as “Mr. Holman.” It was not surprising that as a measure of appreciation for Grandpa, Jerry presented him with a full-scale bronze bust. It was a perfect likeness of Grandpa. For a time it resided in Grandpa’s office, but eventually it was moved to a vacant office-turned storage room on the second floor of the corner warehouse, and after Grandpa died, it wound up amongst the clutter in the billiard room of my grandparents’ house. Somewhere along the line, either Grandpa in a rare instance of whimsicality or UB in a gesture of his own brand of respect, had added an old pair of Grandpa’s eyeglasses to the bust, giving it an even greater likeness to Grandpa—and an eerie one after his death. It had to have been UB who moved the bust into the billiard room after Grandpa had died, and I was struck by the fact that in contrast to all the other clutter in the room, the bust had been placed quite purposefully on the level—and with eyeglasses intact.

Inheritance continues with Part Three: Uncle Bruce.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson