AUGUST 10, 2023 – (Cont.) He was the son of devout Catholics and had grown up in Teaneck, New Jersey, not far from Rutherford. Cliff’s father owned a florist shop, though I wouldn’t learn that part of the story for another decade—May of 2006, to be exact . . .

. . . Cliff and I were approaching the back entrance of 42 Lincoln to check on Uncle Bruce soon after the latter’s triple-bypass surgery. I noted the flowers as we passed—blooming perennials in the scruffy garden along the dilapidated ramp that led up to the back door. “Kind of ironic, isn’t it, Cliff,” I said, “that you get to see some flowers outside the house before you get to see all the garbage inside the house.”

“Postilennia, Crupinallicus, and Speniphoria, and over there, Linneacralius,” he said (to the best of my recollection), almost subconsciously.

“Whoa!” I said, stopping abruptly. “How does a guy like you, who’s into horror stuff, costumes, and with rock ‘n roll in his background know the names of so many flowers?”

“My dad was a florist. I had to work for him when I was in high school. Hated it, but believe me, I learned the names of a thousand different plants and flowers.” . . .

I don’t think Cliff got along well with his father. I don’t think the dad approved of Cliff’s image, the earring, the shaggy hair, the rock star quality to his persona, and I don’t think he appreciated Cliff’s success as an entertainment producer. I met his father in May 2006. He looked worn down, and he seemed even more tired when answering my questions about how he had gotten into the floral business—first as an employee, then as a co-owner, then as a sole proprietor. He had worked hard to run a small shop, and if he’d been reasonably successful at it, he was not a wealthy man. He was serious, conservative, and his tired look and reserved nature contrasted markedly with Cliff’s hearty, “can-do,” ambitious, out-going, visionary approach to life and expansive accommodation of people.

Cliff seemed to hold his mother in much higher regard. She even worked for him at Fun Ghoul, though you’d never know they were mother and son, for they always talked to each other in the most business-like manner. Everyone—even Cliff—called her “Sis,” though no one, not even Cliff, could tell me why. She was a very pleasant and genuine person, who laughed easily, and never said a mean thing about anyone. Even after some of the truth about UB spilled out, she kept her reactions to herself, and continued to show genuine concern for his welfare. Although she exhibited none of Cliff’s brashness, Cliff’s mother must have been responsible for his remarkably generous heart.

Cliff also had a sister, about whom I would hear very little over time. I don’t think they had ever been very close. But then there was Cliff’s daughter, Angelique, about whom I would always hear a lot. He was very proud of her and all of her accomplishments, and he wanted only the best for her, and though Cliff himself had never attended college (I don’t believe anyone in his family had), he assigned high priority to Angelique’s education and worried often and aloud about how he would afford the best for her.

Of Cliff’s former wife, he was not very complimentary. He never said a mean word about her, but clearly they had been a poor match for each other.

“We met during my rock ‘n roll band days,” said Cliff, during one of our many chairlift rides on that first ski trip in Montana. “Not to brag or anything, but I had girls hanging all over me. I had this band, see, and we got pretty good and got a lot of gigs, and we’d play in big venues. Girls would go crazy. I could have any I wanted, but this one girl seemed different and we hung out and next thing you know, we got married. But then after awhile she got weird on me—you know, real obsessed with some things.”

“Like what?” I asked.

“Well, for instance, whenever I came home and walked through the house, she’d get out the vacuum and vacuum everywhere I’d walk. And she insisted on keeping the kitchen so clean it was nuts. I mean, after cooking in the oven, she’d scour the inside with a toothbrush.”

“That’s a little extreme,” I said.

“Tell me about it. I remember a time when we had some friends over for a dinner party. We’d finished eating, and I moved everyone out to the living room for some after-dinner drinks. But my ex-wife—she insisted on staying back in the kitchen to clean up. And I don’t mean simply rinse and stack the dishes or load the dishwasher. She wanted to scrub and wash and dry and do the whole nine yards. I went back and said, ‘Hey, we can clean up after company leaves. But right now it’s time to relax, have a drink or two, just hang out.’ But no, she refused, so finally, I said, ‘To hell with it,’ and went back to the living room to join our friends.

“A while later, our friends got impatient with her too, so they went back to the kitchen to get her. I followed them, and wouldn’t you know it, but there she was—scrubbing the oven with a toothbrush.

“I finally decided, this just wasn’t working out. We got divorced when Angelique was about five.” With that, he pushed off for another run down 2,000 feet of vertical drop.

If Cliff wasn’t an experienced, polished skier, his natural athletic ability would serve him well. To be a good skier, you can’t hesitate, you can’t be tentative, and Cliff hesitated at nothing, was tentative about nothing. As I had seen on the way out to Montana, Cliff was a man of action.

At the half-hour refueling stop at Havre, Montana, Cliff, Cory and I tossed a football around just outside the station front[1]. With each pass, the ball was thrown higher, harder, faster until, inevitably, it wound up inside a small area at the base of a communications tower bounded by a high, chain-link fence with four strands of barbed wire to keep out intruders. A large, redundant, “No Trespassing – Keep Out” sign hung on each of the four sides. The ball was a cheap, rubber one from Cory’s rather substantial inventory, and being largely a stick-to-the rules kind of guy, I was fully prepared to kiss the ball good-bye. Not Cliff.

He looked around to see if anyone with a semblance of authority happened to be watching. He then scaled the fence, arched one leg over the barbed wire, then the other, and jumped down into no-man’s land to fetch the ball and pass it out to Cory. His escape was just as swift. The whole operation took less than 30 seconds. Upon landing on the side of freedom, Cliff looked at me, and seeing my astonishment, said, “Come on, Eric. We’ve got at least another 10 minutes of football left. Why would we let a little fence and barbed wire stop us from taking full advantage of it?”

Cliff had a point.

On the ski slopes of Big Mountain, he followed Cory and me down challenging terrain, and he always kept his wits about him. He cut an impressive figure as he barreled down the slope, much like a large truck blasting its way down an unplowed, winter highway. After several close calls, I decided that it was safer to follow him down the mountain, just in case his “brakes” malfunctioned. Cory, who, as a young kid, was still pretty much in a schussing phase, kept up with Cliff. Uncle Bruce, who was 72 at the time, skied much more cautiously than the rest of us, but I thought it was nothing short of extraordinary to see Cory, then Cliff, then Uncle Bruce coming down the same slope on Big Mountain, Montana, a million miles from Rutherford, New Jersey.

For much of the time, however, Uncle Bruce hung out in the ski lodge lounge, and Cory went in often for hot chocolate, but Cliff was a diehard skier, and I stopped for nothing. “Where did you learn to ski?” I asked on a ride up the mountain.

“You think I’ve learned how to ski?” he laughed. “I’ve been a couple times with Uncle Bruce, that’s all.” I noticed that Cliff called my uncle, ‘Uncle Bruce,’ as much as he called him ‘Bruce,’ and as time went on, I realized that Cliff had, in fact, subconsciously adopted my uncle as his uncle. It didn’t bother me in the least. I figured he’d earned the right to call him ‘Uncle Bruce.’ Besides, it made Cliff seem more like a first cousin to me—my only first cousin, since Uncle Bruce, Mother’s only sibling, had been a bachelor all his life and Dad was an only child.

“You mean you’ve been skiing only a couple of times before this?” I asked.

“You got it. But I played a lot of hockey—high school and even a little semi-pro for awhile.”

“It shows,” I said. But there was much more to Cliff’s background that I wanted to know. “But back to your rock ‘n roll days, Cliff—it sounds as if you were halfway serious about it.”

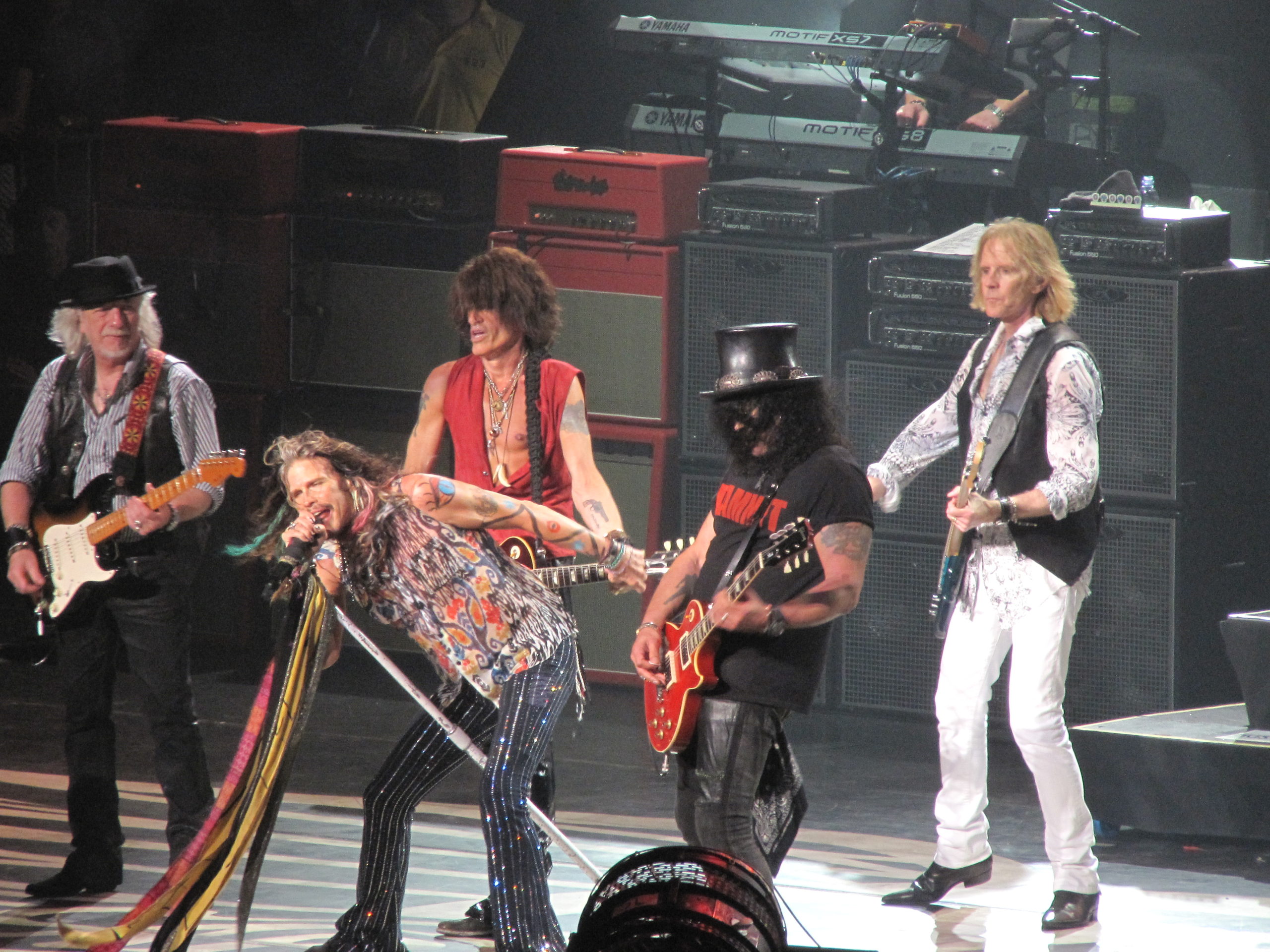

“You kidding me?” said Cliff. “We were dead serious—when we weren’t stoned, that is. We landed some really good gigs, and we even wound up as warm-up band for Aerosmith. That’s how I got into the costume business.”

“Huh?”

“Eric, I know you’re all into classical music, and I don’t know how well you know the rock scene, but it’s all about how you look up there on stage. The more outlandish you look, the more the crowds go for you, so I pulled together these outfits for the band. Steven Tyler—he’s the leader of Aerosmith—he saw us perform and came up to me afterward and said, ‘Hey, Cliff, can you make costumes for us too?’ So I did. And seeing as how I was always into horror stuff—you know Halloween costumes, haunted houses, that kind of thing—I started expanding my repertoire, you might say, and before I know it, I’m looking around for a place where I can open a costume shop. That’s how I wound up in the Holman building.”

“But isn’t the costume biz kind of seasonal?” I asked, as the chair entered the dense fog that had enveloped the upper reaches of the mountain.

“You kiddin’ me? First we’ve got New Year’s—you’d be amazed by how many people go to New Year’s costume parties. Then there’s Valentine’s Day, followed by St. Patrick’s Day parties, Fourth of July, Halloween, of course, and Christmas is always big. Birthday parties are going on all the time. But now we’re doing a lot more than just costume rentals. We do all the entertainment and arranging for big corporate parties[2], restaurant openings, movie promos—all kinds of stuff. It’s wild[3].

“Really,” Cliff said, as he leaned over the safety bar and peered into the fog, “I really shouldn’t even be away for a whole week . . . Holy shit! I’ve never seen fog like this!”

“It’s quite common here at Big Mountain,” I said, having experienced heavy fog on each of my previous trips to the place.

“But on the other hand . . .” Cliff laughed, as he leaned back in the chair. “How could I miss a ski trip with you, Cory, and Uncle Bruce? I’m telling you, Eric—Uncle Bruce is a flat out riot. Jesus, but they just don’t make people like him anymore. Did I tell you that last year I took him with me to the national convention of costume manufacturers in Chicago? I know a lot of the top players, and I was showing him around, introducing him to people and he was eatin’ it right up. Uncle Bruce, who’s always wearing some kind of costume of his own—you know, with that toupee of his, and the trench coat, the pork pie hat, the clip-on tie—was right at home there, and you know, Eric, it was really a lot of fun seein’ him having so much fun.” (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] Both Cliff and Cory were inveterate football fans and rooting for the Cowboys in Super Bowl XXX.

[2] Including the Trump Organization for years running. More about that in due course.

[3] Years later Cliff was in charge of some big celebrity charity fundraising event attended by James Earl Jones, among other notables. When Cliff and Jones wound up sitting next to each other at the head table, they got to talking. When the “Voice of Darth Vader” learned about Cliff’s costume business, Jones told Cliff that one regret he had about his role in Star Wars was that he didn’t get to keep a Darth Vader costume. Ever the promoter, Cliff immediately offered to outfit Jones with a Darth Vader outfit. Soon thereafter Cliff followed up on his word to the gushing praise of the famous actor.