AUGUST 30, 2023 – After we signed in at the security desk, Cliff led the way to the cardiology unit and strode straight into UB’s room. “Look who just arrived from Minnesota!” said Cliff.

“Ha!” said the patient, seated in a large recliner next to his bed. “Great to see you!” His eyes lit up.

“I thought I’d come out here and make sure you were behaving yourself,” I said, shaking his hand.

“Well, I’m having quite an adventure, but the staff here is excellent, really excellent.”

He appeared as chipper as ever, and in fact without his bizarre toupee (I guessed that it had been removed prior to his going under the knife), he looked better than ever. He certainly didn’t look like a guy in his 80s—or even his 70s—who was just three days out from open heart surgery. We visited for about an hour, during which he gave me a detailed account of the emergency that had precipitated his operation; his understanding (obtained, no doubt, from extensive interrogation of the doctors) of the technical aspects of the procedure itself; and a full description of the post-op care and monitoring by his doctors and nurses. His voice sounded like gravel grinding in a gearbox filled with phlegm but not in the manner of an old person—there was plenty of energy in the grinding. He didn’t look old, and he certainly wasn’t thinking old. He was more than lucid. He was as sharp as a carpet tack. I marveled at his resilience and mental acuity. Somehow I managed to forget about the Serb, my sense of guilt and the chaos back at 42 Baghdad Street.

Cliff and I promised to visit UB again the next day. As we found our way to Cliff’s van, I wondered if UB was at all concerned about my access to all the horrors of his house, all the dirty secrets on his computer, in his office, the co-habitation of his “friend” Alex. Surely UB had to know that after the Great Fire, Cliff had told me everything. Yet UB hadn’t asked what I’d be doing that evening, what I’d be doing the next day, or even how long I was planning to stay in New Jersey. Maybe, I thought, he’d deluded himself into believing that if he didn’t question me, it wouldn’t raise any suspicions, and without suspicions on my part, his secrets would be safe from me . . . and from the rest of the family.

* * *

That night I stayed at Cliff’s house. Over a late dinner with a fully necessary amount of wine, Cliff and I shared with Jeanette, the bizarre encounters of the day. Being a very perceptive individual and having spent a fair amount of time observing UB, she imparted her insights into UB’s relationship with Alex.

“Your uncle is being played like the old fiddle,” she said, pouring more red wine into my glass.

“Well,” I said, intending to take a sip, which, in my eagerness to respond, turned into a gulp. “Based on what I’ve seen and heard thus far, I’m not sure. I mean, I’m not sure that it isn’t a case of Uncle Bruce having stalked Alex, then having used money to lure him into that trashed out house and to imprison him. And on top of all that, my uncle has been masquerading as ‘George’ and telling gigantic fibs about his past. My uncle is insane. We all know that, and his insanity has led to some huge fantasy, and this poor Serb is at the middle of it. But in any event, we told Alex he had to pack his bags and get the hell out of town.”

“Don’t be so sure he isn’t coming back,” said Jeannette, adding a little wine to her own glass. “Uncle Bruce is gay. This man Alex is gay. Uncle Bruce is old. Alex is young. Uncle Bruce has money. Alex has none. The situation is really clear to me: Uncle Bruce needs Alex because he fulfills a fantasy—a young gay man who needs him. For Alex, Uncle Bruce fulfills a fantasy: he’s got money. And based on your description of this guy, Eric, I wouldn’t be surprised if he’s on drugs, in which case you have a much bigger problem on your hands. He could be taking your uncle to the cleaners. Getting rid of Alex is going to involve more than putting him on a plane.”

“You might be right,” said Cliff, “but we have to start by putting him on a plane. And we also have to get that house cleaned up. It’s a disaster. No one should be living in such filth. Tomorrow I’m going to hire the Merry Maids. They’re a cleaning crew that I’ve used before for various events. They do a helluva job, and we’ll get them in there first thing and make that place semi-livable. We’re also gonna have to make sure that Alex is, in fact, packing his bags for the trip back to London. But before he goes, we should probably take him over to the hospital for one more good-bye.”

“That would be the kind thing to do for Uncle Bruce,” said Jeanette. “I mean, even if he is a no-good drug addict mooching off Uncle Bruce, clearly Uncle Bruce is infatuated with him, and if Alex just leaves without saying good-bye, it’s going to be rough on Uncle Bruce, who just came out of major heart surgery, and Alex’s departure with no good-bye could be a shock and not good for Uncle Bruce’s recovery.”

“Yeah, “ said Cliff, “except what you’re saying about Alex being a drug addict and cleaning out Uncle Bruce’s cash is giving me a heart problem.”

All three of us laughed. But it was decided. In the morning, we’d hire the Merry Maids. In the afternoon, Cliff would take Alex to the hospital for a final farewell. Then we’d make sure Alex was gone. Gone for good.

* * *

The next morning, Cliff and I crashed in on Alex at about 8:30. Alex still looked shell-shocked, at least judging by the shakes and the fear in his eyes. “Good morning, Alex,” Cliff said in a booming voice.

“Good morning.”

“So what’s the word, Alex, on your flight to London. Do you have it booked?”

“Yeth. I’ve got a flight that leavthz at theven thith evening.”

“Good, good. That’s good, Alex. So here’s the plan. Today we’re gonna get this pig sty cleaned up, okay? And you’re gonna help us.”

“Thure.”

“And then I’m gonna take you up to the hospital to say good-bye to Bruce.” Cliff said, turning to me and winking. “And I do mean Bruce and not George.”

“Yeth, yeth.”

“Then I’ll bring you back here and you can call a cab to the airport. You’re leaving from Newark, right?”

“Yeth, Newark.”

“Good, then it’s all settled. Let’s get to work.” I admired Cliff’s complete civility toward the Serb, combined with uncompromising firmness and directness.

In keeping with our agreed-upon modus operandi, Cliff and I led Alex up to the “floor of horrors” and tried to gross him out the best we could with all the evidence of UB’s madness, so that if Jeanette was right—that from Alex’s standpoint, the relationship was purely about money—the Serb might think twice about ever returning to Rutherford. As the morning wore on, I would find disturbing evidence of UB’s infatuation with Alex—snapshots and later, CDs full of photos of him, many taken when Alex was unawares. Several were taken when Alex was in the shower. Gay or not, Alex reacted strongly and spontaneously to these.

“Oh Gahd,” he said. “The man ith thick.”

“Yes, you can say that again,” I said. “All the more reason for you to stay away from him.”

When we deployed Alex in the massive cleanup of UB’s house, I thought I saw genuine fear and disgust in Alex’s reactions as the process uncovered more clandestinely shot photos, unsent greeting cards to Alex and signed, “George,” photo-copies of one-dollar bills with the portrait of “George” cut out, a whole folder of mint-condition, one-dollar bills. “Why do you suppose?” I said to Alex as I showed him a sample. “Because each has a clean ‘George’ face?”

Before the shaking leaf could answer I found under a batch of crap, photocopies (made on the sly, of course) of the contents of Alex’s wallet. “And look at this,” I said, hoping to evoke further dismay. “He dug through your billfold and copied stuff.”

“Oh Gahd!”

Alex repeated the phrase continually after we conscripted him into taking inventory of the cartons full of gay porno video-tapes (148 in all). His shakes went into overdrive when I showed him UB’s rating book.

Nevertheless, Cliff wasn’t sure that Alex was shocked enough. After sending him on a mission to run downstairs for some garbage bags, Cliff laughed. “Eric, I know a way to scare the crap out of Alex. Scare him so bad he won’t come back here in a million years.”

“How’s that,” I said, knowing Cliff had some creative idea up his sleeve.

“You know that corpse in a coffin that’s in the hearse stored in the garage? You know, my deluxe Halloween prop that my Hollywood costume designer buddy made for me?” [See 8/27 post]

“The one you said makes people throw up even when knowing it’s not real?”

“Yeah. We could string that thing up in the basement, then ‘discover’ it,” said Cliff with the aid of air quotes, “scream and holler in hysterical fright over the thing and then come back upstairs and drag Alex down to see it; ask him what he knows about it, then fake a call to 9-1-1. Or better yet, after hanging the corpse from a joist in the laundry room, we could tell Alex to go down there to fetch a plastic bucket in the laundry room that’s probably by now thick with cobwebs and let him call 9-1-1 after he discovers the dead body.”

I slapped both hands onto my head. “Cliff, that’s brilliant! You’re absolutely right. That would turn Alex into a babbling fool for the rest of his existence. He’d never recover from such a thing, and we could be assured forever that he would remain in a state of non-recovery as far away from here as an airplane could fly him.”

In retrospect, we should have followed through on Cliff’s idea for the very reason we didn’t: it was excessively outlandish, and especially in the years to come we’d need something excessively outlandish.

The Merry Maids appeared at about 9:00, a whole crew of Hispanics led by a bright-eyed, pretty young woman from the Dominican Republic. They reacted visibly as we led them around the house, and chattered animatedly among themselves in Spanish. Cliff asked for a translation, though neither he nor I really needed it.

“Well, we whar saying,” the woman said, “thaht deez plez is reely dahrdy, reely trrashee. Wahrs dan we see in a lahng, lahng tieme. But we wahrk hahrd today and cleen eet up good.”

“Well that’s great,” said Cliff. “That’s why you’re here. I want you to go crazy and clean this place up the best you know how. Upstairs—here, let me show you.” He led the Merry Maid upstairs, and I followed her.

“Oh, eets even wahrs up heer,” she said.

“Yeah, we know. That why I’m gonna pay you a $200 bonus,” said Cliff, ever the entrepreneur, “if you can have this place halfway livable by 2:00 this afternoon.”

About four hours later, the Merry Maids had indeed rendered the house “halfway livable.” The kitchen and bathrooms had been scrubbed, mopped, and cleaned of trash. The cat room got similar treatment, as did UB’s bedroom, the rest of the upstairs, and the dining room. What remained in chaos were the billiard room, the library, and the recycling center at the rear of the house.

The library would require an army of forensic accountants—we couldn’t just throw out all the papers. We might be tossing a few bonds, stock certificates, rent checks, a stash of “George Washingtons,” maybe a will, bank and investment account statements and other important papers along with all the scraps.

A complete cleanup of the billiard room and the recycling center would require a forklift and a bulldozer, equipment that the Merry Maids didn’t have. The Merry Maids stuffed no fewer than 36 extra-large Hefty bags with trash. That number didn’t count the heavy brown paper yard-waste garbage bags that had already sat in the kitchen—each full to the brim. Cliff paid the tab, bonus included, out of his own wallet.

“You shouldn’t be paying for this, Cliff,” I said.

“No, I shouldn’t. No one should have to be paying for this, but Uncle Bruce is such a pig, such a stingy pig, what are we gonna do?”

I felt embarrassed. I knew I didn’t have but 20 bucks in my wallet, and I hadn’t carried a checkbook with me in at least 10 years. “I guess you add it to your bill, Cliff.”

“My bill. Right. I lost track of what’s on my bill to Uncle Bruce. But you know what? I’m doing this because he doesn’t deserve to live in filth. He just doesn’t. And just because he can’t understand that doesn’t mean we have to let him live this way.” Admirable. But it didn’t address why I wasn’t insisting that the family, at least, would reimburse Cliff.

“Yeah,” said Cliff. “I’ll try to keep track of stuff.” Not until a decade later would Cliff start keeping track, but by then the dumpsters he was ordering by the dozen for cleaning out the warehouses were costing a small fortune.

* * *

The Merry Maids had bagged a lot of trash, but Cliff had thought it was prudent to keep the lid on the porno tapes and UB’s rating books. Together, Cliff and I boxed them up. “While we’re at it,” I said, “we might want to preserve some of the rest of the evidence of UB’s bizarreness. You never know when we might need it for a guardianship or conservatorship proceeding or, if it should come to it, a restraining order against Alex.” Thus, alongside the porno tapes and rating books, we crammed in such things as the Alex pictures, the photo-copy of one-dollar bills with “George’s” portrait cut out, the unsent greeting card addressed to Alex with cut-out portrait taped to the inside over the signature “George,” and other bizarre evidence of UB’s obsession with Alex.

“Now, where to store it,” said Cliff.

“Well,” I said, “there happens to be a row of big, old storage warehouses about 60 feet from the back door of the house.”

“I don’t know about that.” Cliff laughed. “With this stuff smoldering over there, the place could catch fire.”

“You got a point. And didn’t you say the fire chief once told you that if the warehouses caught fire, the fire trucks would be late?”

“And that would be a bad thing?” Cliff laughed again. “No, Eric, I’ve got a better idea. A perfect place for this bullshit. A place only you and I will ever know about.”

“Where?”

“The trunk of the Cadillac.”

“Cars get broken into, Cliff. Why is that so safe?” As I raised the question, it dawned on me that I hadn’t seen UB’s trashed-out 1984 burgundy Cadillac Seville, which, on past occasions had always been parked in the driveway directly across from the back door of the house.

“The ol’ Caddy is pretty much buried in garbage in the three-stall garage next to the warehouse garage. The trunk would be the last place anyone would search. Grab that box,” Cliff directed. “I’ll take this one and show you the way.”

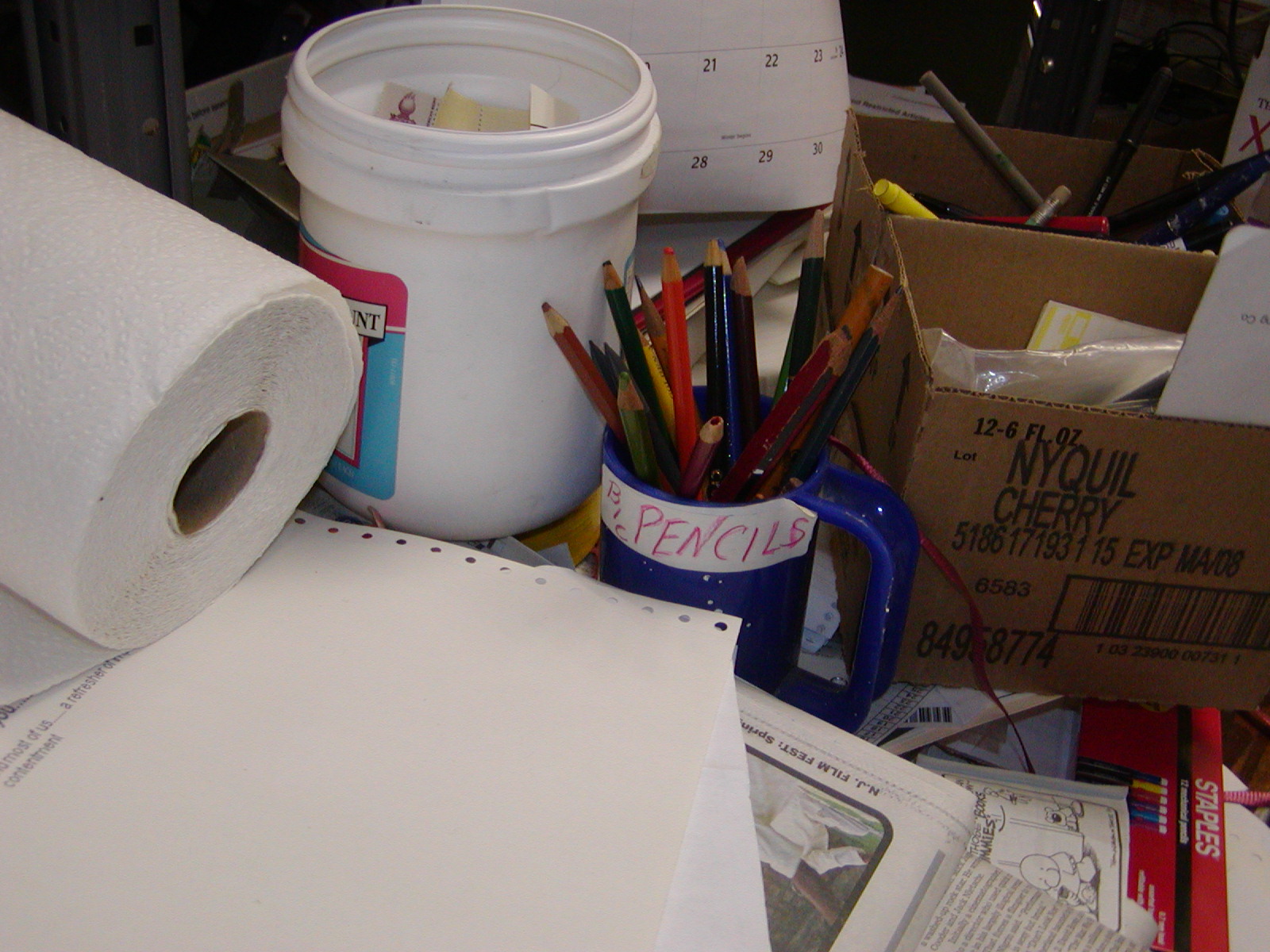

With the boxed-up contraband, we staggered out of UB’s bedroom, down the stairs, through the house and out the back door. Cliff let us through the side door of the garage and into yet another venue of trash that was a hidden monument to “42 Baghdad Street.” Under six-foot high mounds of newspapers, were discarded carpeting, empty containers, cardboard boxes, plumbing fixtures, left-over construction materials, garden tools, ladders, paint cans, radios, bags of potting soil and fertilizer, ski equipment, and a full collection of old, greasy jackets and overcoats. Exposed here and there to the discerning eye was the headlight, the left rear fender or the driver-side windshield of one of the three decommissioned automobiles that sat parked under the piles of trash. Upon closer investigation, I identified the cars: UB’s ’73 Mustang convertible (top down), a vehicle from the first half of the previous century, and . . . the ’84 burgundy Caddy.

We set the boxes down on one of the only remaining patches of unoccupied real estate inside the capacious but stock-full three-stall garage. Cliff then thumbed through his collection of keys while I removed the crap on the trunk lid of UB’s version of a C-130 cargo plane. When the faded burgundy cargo door was lifted, it revealed a bay full of yet more junk. I removed some and consolidated the rest.

“We’ll call it the ‘trunk of horrors,’” said Cliff, as he lifted the boxes of horrors and maneuvered them into the newly created cargo space. “No one’s gonna know what’s here except you and me. As gross as those tapes are, as insane as the rest of the bullshit is, it’ll all be safe here—safer than it’d be in the garbage cans that are put out on the sidewalk for weekly pickup. And when we confront him about bullshit behavior, he denies it or gives us any grief whatsoever, we can haul this crap out and use it to knock some sense into his head.”

Or compel a judge to sign an order, I thought, if and when UB ever decided to fight a guardianship or conservatorship petition.

* * *

Late that afternoon while Cliff took Alex to say good-bye to UB, I plowed through the madness in UB’s office over in the warehouse—a smoldering compost of junk mail, old tax returns, $50 bills, uncashed rent checks, ancient check registers, current statements for investment accounts, stray 1099 tax forms, several corporate tax returns from the 1980s, a demand letter from a lawyer suing over a “slip-and-fall” on warehouse property, newspaper clippings from The New York Times (featuring fashion design), and numerous unsent, illegible rambling letters to Alex, signed “George.” More evidence, I thought, to be added to the trunk of the Cadillac, except there wasn’t space enough there for a flea to move or even change its mind.

In the midst of the mess, I found a checkbook and register for a joint account in UB and Gaga’s name. I examined the register and discovered that a number of checks had been written recently, one to Alex for $7,500. The two obvious questions smacked me in the face simultaneously: Why was UB giving such a large sum of money to the Serb? And what was UB doing with a joint account with Gaga, who had been dead for over 11 years? Wasn’t he the executor of her estate and trustee of her trust? Shouldn’t half the assets in her trust and estate have been distributed to Mother long ago?

A while later Cliff phoned to let me know he and Alex were back from the hospital and that a cab would be showing up in another half hour to take Alex to the airport.

“Cliff, I found a checkbook and a register for an account that Uncle Bruce still maintains with Gaga, even though she’s been dead for well over a decade. But here’s the disturbing thing—he sent Alex seventy-five hundred bucks a few weeks ago.”

“I knew it!” said Cliff. “I knew he was getting big money from your uncle. Now the question is how much? You coming over to the house?”

“I’ll come over now.”

“Good, because we need to ask Alex about the check before he leaves.”

Moments later, Cliff was directing Alex to take a seat at the kitchen table. “Eric has something to ask you,” Cliff initiated the interrogation.

“Yeah, Alex, as I was going through things over in my uncle’s office, I discovered that he had written you a check for a whopping seventy-five hundred dollars.”

“Yeth,” said Alex, fear in his eyes.

“How much money has he given you besides the $7,500?” I asked.

“I don’t know.”

“What do you mean you don’t know?” In my anger my eyeballs felt enlarged. “Is it closer to $10,000 or $20,000?”

“Gahd, I don’t know!”

I had my answer. Now I was shaking.

“He keepth wanting to give me money, and I’ve thtold him I don’t want hith money but he keepth thending it.” He was on the verge of tears.

I suddenly felt sorry for the pathetic creature. According to his earlier account while we were stuffing Hefty bags, his parents had died when he was a teenager. His city had been heavily bombed by NATO planes with the U.S. in the lead. He had found his way to England, scraped by. He was a clothing designer trying to launch several fashion lines. He was a mess. He had been staying in a trash house with an 83-year old crazy man who calls himself “George” even though that’s not the man’s name and who told some very big fibs about his background and who was holding this foreigner captive by having hidden the his passport. And on top of all that, this cowering human being with a bad case of the shakes was threatened by a big hulking guy who owns a Halloween costume shop and specializes in “horror” and by the 83-year crazy man’s nephew who just breezes in from a distant part of the country to help lay down the law.

“So, what did you do with the seventy-five hundred dollars?” asked Cliff.

“I thtill have the check,” answered Alex.

“Then you need to give it back,” I said.

“I know, I know. I will,” he said. “But I left it in London.”

“Then as soon as you get back to London,” said Cliff, you need to send it back to us, you hear?”

“Yeth, I will thend it back right away.”

“If you don’t, we’re comin’ to get it,” said Cliff. “And we won’t be knockin’ first.”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson