JULY 27, 2023 – It wasn’t until many decades later and Gaga was lying on her deathbed in the hospital, when I learned the origins of Uncle Bruce’s connection with the state of Vermont. It was 1994—four years before the fire, of course, and all that it revealed, and thus my accepting (if not positive) impression of him was still very much intact. We had just returned to 42 Lincoln after supper at the Candlewyck Diner, following our time at the hospital. Upon entering the back of the house, we sat down in the kitchen,[1] where I initiated a little small talk. One thing led to another—Uncle Bruce was always game for delving into one subject or another, and it didn’t matter much how you started or where you finished.

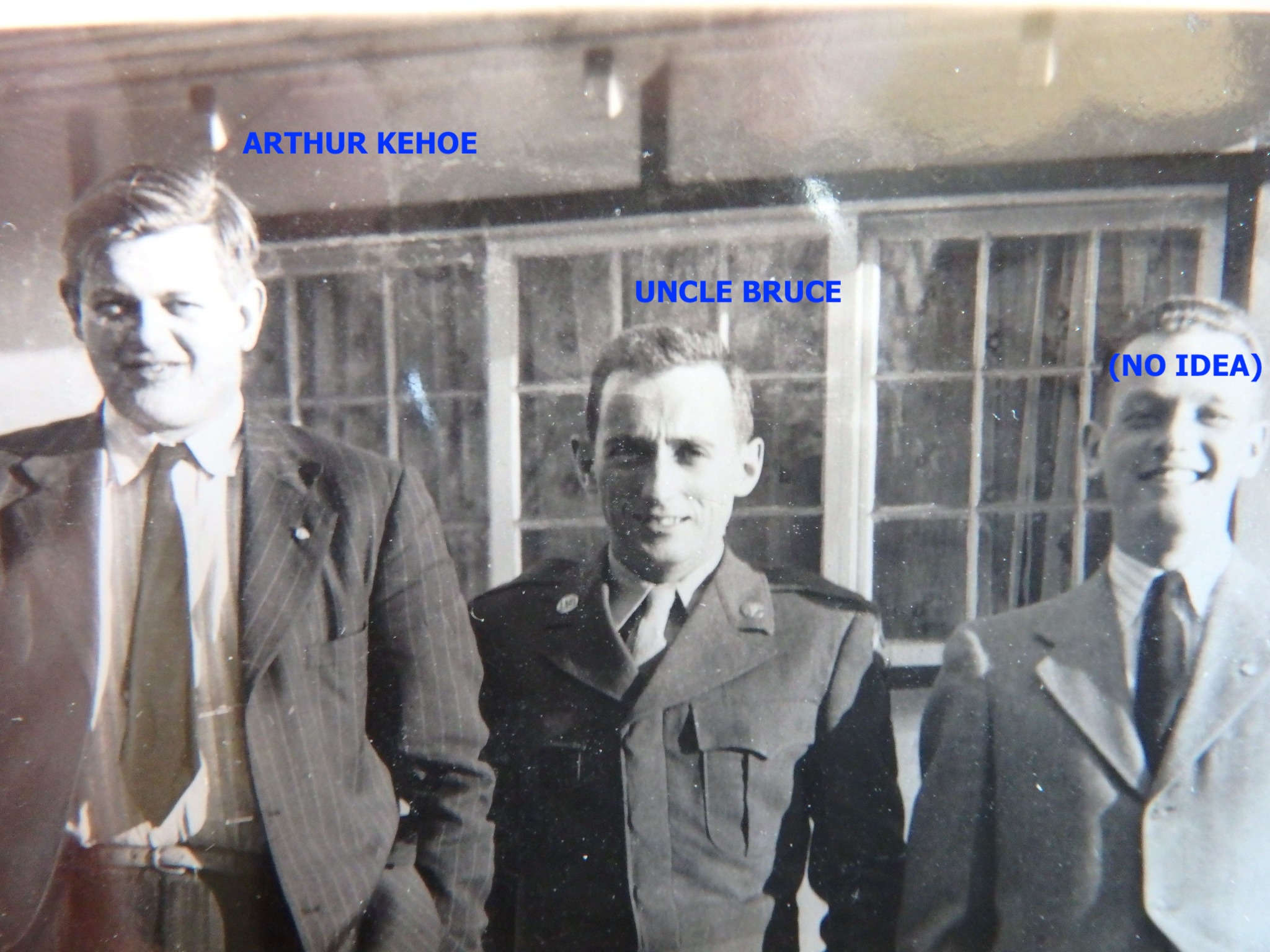

Somehow, we happened upon the subject of his ailing friend, Arthur Kehoe, who lived in a big Victorian house several blocks away. Over the years, I had met Arthur several times, and I knew that he and Uncle Bruce had been friends since an early age. Uncle Bruce told me that Arthur was in pretty bad shape, let out a sad sort of chuckle tinged with resignation, and said, “I think he’s probably not long for this world.”

Uncle Bruce then looked at his watch. His gesture caused me instinctively to look at the clock just above the stove—the one on the wall, not the one that was actually part of the stove or the one still in its plastic packaging, perched on top of the back of the stove and leaning against the wall. “I suppose it’s too late to see him,” Uncle Bruce said, seemingly to himself. It was 8:30. “Well, maybe not,” he said to me.

“Let’s go,” I said. It was encouragement enough. He grabbed his lump of keys off the kitchen table, gave his toupee the patented three taps, and led me out the back door into the cold November air.

“So how long have you known Arthur?” I asked, pulling tight the belt to my trench coat, as Uncle Bruce strode down Gaga’s handicap ramp.

“Since we were kids.” Uncle Bruce seemed oblivious to the significant difference between the inside of the house, which was still in the torrid zone on account of Gaga, even though she was in the hospital and would not be returning, and the near-freezing temperatures outside. “Arthur’s father was a brilliant engineer,” he continued, “and a top executive at Con-Edison, responsible for converting the entire Northeast from direct current to alternating current.”

After springing off the rotting end of the handicap ramp, Uncle Bruce opened the sloping chain-link gate, the corner of which rested on the sidewalk, and stepped onto the broad driveway, which separated the wilted jungle gardens behind the house from the haunted old warehouse on the other side. He then slowed his gait noticeably to a more contemplative pace. It was in marked contrast with his usual short, frenetic steps.

“His father was like a father to me,” said Uncle Bruce. I had never before observed him say anything so wistfully.

His comment and inflection reminded me of what Mother had once said about Uncle Bruce—that he had been quite sickly as a kid, and how Grandpa was always working hard, often out of town on business, and I knew from my own observations that father and son didn’t seem to talk to each other much, even though they lived under the same roof and worked in the same enterprise together. And when they did talk, it was with an economy of words, just enough to communicate a question or information, and only about something practical and immediate. Once in awhile, over the years, I had even heard Uncle Bruce bark at Grandpa with a sharp word or two. As Uncle Bruce continued glowingly with his description of Arthur Kehoe’s father, I saw more clearly what I had suspected for a long time—Uncle Bruce and Grandpa had never gotten along.

“The Kehoes always had big Sunday suppers,” said Uncle Bruce cheerfully, “and I was usually there at the table too, and Arthur’s father would teach us all kinds of things. He really was very brilliant, and he insisted that we know how things worked. To me he was very interesting. In the summers, they had picnics in their backyard, and I got to be at those too, and Thomas Edison was there—he and Arthur’s father were close friends—and they were like a family to me.”

“Thomas Edison?” I said. “The Thomas Edison?”

“Yep.” Before I could follow up on this most astonishing disclosure, Uncle Bruce continued his unusual reminiscence. (I decided not to interrupt. I had rarely heard Uncle Bruce talk about his youth but realized too that I had never bothered to ask.) “I remember one meal at the house—we were seniors in high school—and Mr. Kehoe told Arthur and me that he was going to put us on a train for Burlington, Vermont so we could visit his brother, who was the provost at the University of Vermont.”

“Really?” I said. “Just like that?”

“Just like that. Mr. Kehoe said we could get a really good education at that school. The Kehoes were from Vermont originally, and with his brother there and all, Mr. Kehoe was biased of course.”

“So did you go?”

“We went. It must have been a week or two after that. Arthur’s uncle met us at the train station, took us over to campus and gave us a complete tour. Later, he arranged for everything for us to go there. I didn’t have to do a thing. He handled our application, got us a dorm room, everything.”

“That’s amazing.”

“It was!” It seemed as though Uncle Bruce hadn’t told the story in a long time—if ever. “That’s where I learned to ski, you know.” I felt bad, given all the time that we had spent skiing in Vermont together.

Soon we were at the front door of the large old Kehoe house. I had been there for the first time back in 1964. The memory flashed to the forefront . . .

* * *

. . . I was not even 10, and Uncle Bruce, Mother, Jenny and I were guests one deliciously warm, summer evening. A large guy to begin with, Arthur made an even bigger impression with his gregarious nature.

“Come in, come in!” he said, gesturing broadly. “You’ve got the whole gang, I see,” he said. “The whole gang from Minnesota. Good to see you, Sis, and who do we have here? The kids! Wow Brucie, they’re growing up in a hurry, aren’t they?” He turned to Jenny and me and extended a large paw of a hand. “Hi, kids. I’m Arthur. How do you do?” He wore a white dress shirt and big, brown, baggy dress pants, and his shoes were huge. He had big round eyes and a small mouth on a face with odd folds, and his ears stuck straight out. This man Arthur was homely enough to be instantly likeable. I had no idea what he did for a living, but judging by the size of the house and the presence of a maid who took our orders for lemonade, I could tell that Arthur was rich—maybe as rich as Uncle Bruce, Gaga and Grandpa. He was friendly too, and he made a very favorable impression by giving Jenny and me as much attention as he gave Mother and Uncle Bruce.

By one means or another, probably from Mother early in conversation, Arthur learned that I was a budding philatelist, though at the time, I had no idea that that’s what a stamp collector was called. Dad and my Grandpa Nilsson had been quite the philatelists and had even published in the 1940s a philatelist periodical called The Post with international circulation. By the time I came along, they were largely out of the stamp collecting business, but they gave me a several old albums, a few collections, and a little encouragement. It so happened that Arthur himself was a major philatelist, and to make conversation with me, he asked, “So what’s your favorite stamp?”

I’m sure that Arthur was thinking “favorite” as in “notable and valuable,” as in “the Viking Ship” of the 1925 Norse-American Commemorative Issue[2], or stamps comprised by the “Columbian Exposition Issue of 1893.[3]” But I was thinking on a whole different plane as in, well, plain postage stamps. The year before our visit the postal service had issued Civil War centennial stamp commemorating the the Battle of Gettysburg, and I remember having seen in a magazine a set of stamp designs that the U. S. Postal Service was considering. Being a young Civil War buff at the time, thanks to Dad’s own interest in the subject and his large-volume American Heritage Civil War book, which, on a regular basis, I pored over in the den at home, I had noticed when the final selection had been made and put into circulation. Thus, when Arthur asked about my favorite stamp, I replied in the simple language of a 10-year old, “The Civil War stamp.[4]”

Arthur had no idea what I was talking about. The recently issued stamp, already in use as an ordinary postage stamp, was probably to him what a cheap, folding chair available at a discount store would be to an antique furniture dealer. However, when I explained, he caught on and in a big, loud voice, said, “Oh, of course! Yes, a very fine stamp! Yes, of course. I know the one.” How could a kid not like a man like Arthur? A man whom I was apparently welcome to call Arthur, not Mr. Kehoe. And he was Uncle Bruce’s close friend besides.

Arthur deepened his positive impression by inviting me down to the basement for a game of ping-pong. Uncle Bruce accompanied us. I don’t think I’d ever held a ping-pong paddle, let alone played a game. Arthur was patient. He attempted to give me a little instruction and showered me with encouragement as I chased balls on the floor at my end of the table and as he bent his big frame to recover bouncing balls on his side.

“Have you been playing much?” asked Uncle Bruce.

“Nah!” said Arthur in a soft growl. “Your Uncle Bruce and I used to play a lot of ping-pong, Eric. But he got tired of losing so I had to find real competition.”

“He hit the ball so hard you couldn’t see it!” said Uncle Bruce. “How was I supposed to play when I couldn’t even see the ball!” Both men laughed. “You see all those tallies on the wall?” Uncle Bruce said to me. I looked at the plastered wall behind Arthur and noted the scores of tally marks. “Those are all the ‘wins’ by Arthur. He brings people down here to his ping-pong room, demolishes them, and then marks his ‘wins’ on the wall.”

“A man has to do something important with his life.” Both men laughed again. “Eric, how about more lemonade?” Mercifully, Arthur gave me a face-saving way out of any further humiliation at ping-pong. Now, in 1994, as Uncle Bruce pulled his hand out of his coat pocket and let himself into Arthur’s house without having bothered to knock or ring the doorbell, I recalled the scene that had immediately followed the ping-pong 30 years before. It was in the kitchen—an industrial-size kitchen it seemed—and I remembered that there were several women, I can’t remember how many, maybe Arthur’s mother, a sister, a sister-in-law. They were direct and confident sounding, and talked more like men than like women, as they visited with Mother . . .

* * *

. . . “Hello!” Uncle Bruce shouted, as I snapped back to the present and we passed through the doorway. I peered about and was struck by how vacant the house looked. The living room to the right was devoid of furniture, and the spacious dining room to the left of the entryway, looked equally abandoned. Straight ahead was a grand staircase and off to the left upstairs was a long railing on the outside of a kind of mezzanine, which provided access to rooms behind it. A young—maybe 30—delicate Asian woman in a plain, light yellow dress leaned over the railing to see who had broken the quietude that filled the house.

“Oh, hi Meestair Hohman,” she said, walking to the top of the stairs. “You cohm to see Ahtoor? Cohm ohn ope.”

“Arthur’s aide,” Uncle Bruce said to me softly. As the woman walked back along the railing and returned to the room from which she had appeared, Uncle Bruce offered further explanation in a low voice. “She lives here with Arthur. Not sure what the set-up is. No one really does. She’s been taking care of Arthur for a while now. She’s from the Philippines.”

With heavy footsteps, Uncle Bruce climbed the stairs and led me into a front room where we found Arthur—along with a lot of newspapers, magazines, paper bags and tissue boxes—sprawled out on a bed.

“Brucie,” said Arthur. Apart from how he looked, his opening utterance confirmed that the man was not well. He wore a sleeveless T-shirt and a baggy old pair of pants—similar to the ones that I had remembered him wearing so many years ago, when he was in considerably more robust health. His hair was sticking out every which way, his face looked pale, and his big, bare feet were a sight to behold. Every nail was discolored and over-grown, and I thought, the surest way to tell that an old person is not getting proper care is by looking at their feet and toes. If the Filipino woman was Arthur’s aide, what the hell was she “aiding,” I thought, except herself with his money?

“You remember this guy?” said Uncle Bruce.

“Do I remember?! Of course. This has got to be your nephew, Brucie. Eric! How ya doin’?” Arthur wasn’t exactly on the road to recovery. He was nowhere close to that road, but his greeting brought a positive effect to his voice, and at a minimum I knew that our visit was a welcome break from the despair that surely accompanied his condition. I shook his hand and returned the greeting.

“As you can see, I’m not doing so well myself,” he said. “Got everything wrong that a guy could have wrong with him.” Just then, he let out a bad cough, as if some black malady within his lungs had been called to speak. The Filipino woman made a feeble attempt to straighten out some of the newspapers on the bed. “This is Maria,” he said. “She takes care of me.” Maria smiled nervously.

With considerable effort, Arthur sat up and shifted his unsightly feet across the bed to the edge and down onto the floor as he pivoted on his rear end. He rested his weight on his left arm and hand and combed the right side of his head with his other hand. “What brings you to Rutherford? Your grandmother, I suppose,” he said.

“Yeah, she broke her hip. I was out here on business, so I figured I’d go visit her.”

“Not good, not good. The fact she broke her hip, I mean. How’s she doin,’ Brucie?”

“She’s in a lot of pain, I think,” said Uncle Bruce. “We’re trying to manage the pain, but that’s about all that we can do at this point. Manage the pain and wait and see.” He paced across the other side of the room in a way that showed how familiar he and Arthur were, as if they were brothers living in the same abode, not just friends living several blocks from each other.

“What’s your business out here, Eric. You’re a lawyer, aren’t you?”

“Yeah, but I work at a bank now.”

“What’s the name?” the speed of the question surprised me.

“Norwest Bank. It’s Twin Cities’ based but does business all over the country.”

“Really. What area of the bank?”

I had no better idea then about Arthur’s vocation—or former vocation, since I figured he had long ago retired—than I had had 30 years before, and I wondered if he would have any point of reference to my rather arcane world at Norwest Bank. “Corporate trust,” I said.

“Corporate Trust?!” These two words had the improbable effect of injecting color into Arthur’s pale countenance. “Why that’s where I worked for 35 years—corporate trust.”

“Really,” I said, dumfounded. “What bank?”

“Chemical Bank[5] over in Manhattan. Yesirree. Corporate trust for 35 years. I know all about it.”

“Have you gone through all these yet?” Uncle Bruce broke in. On a card table a few feet from Arthur’s bed was a mountain of files and folders and envelopes of all shapes and sizes. Among the mix, sheets of postage stamps stuck out. Some of the mountain had spilled onto the floor around the table, as if a giant mudslide had occurred a while ago. Uncle Bruce picked up some of the items off the floor and gave them a passing glance.

Arthur looked over his shoulder at Uncle Bruce. “No,” he said. “I’ve been working on those, but I haven’t decided what to do with them. I have no use for them, Maria has no use for them. Maybe you want them Brucie?”

“Oh, gosh,” Uncle Bruce said almost under his breath, wrinkling his nose, as he sat down on a chair and casually examined a sheet of stamps. “What would I . . .”

“Huh?” Arthur interrupted him.

Uncle Bruce laughed as he looked at me. “We’ve got way too many things already,” he said. “What would we do with all these stamps?”

“I don’t know. They’re worth something, but they’re not what a serious collector would want.”

I looked around the room and saw the mark of a guy who rivaled Uncle Bruce for the national eccentricity award. Several boxes of cereal were squeezed next to a row of books on a bookshelf. A lamp with an upside-down shade and a long pull chain stood in a corner, and any number of chairs served as over-loaded tables, piled high with so many things, your mind had to slow way down just for individual items to register: a shoe box here, a large packing box for a radio there, a stack of newspapers on another table-chair, a pile of junk mail on top of laundry on yet another. It looked a lot like certain rooms back at 42 Lincoln. What kind of aide was this Maria, anyway?[6]

Before long, the two old friends were reminiscing about their halcyon days in college. “Remember the time you were out selling tickets for the Rutgers game, Brucie? You had to sell a certain number in order to cover the cost of our team going way down there from Burlington.”

“I do remember that,” Uncle Bruce said, putting down several more sheets of stamps that he had been looking over.

“You see, Eric,” said Arthur, “your uncle was manager of the UVM football team and did a helluva job.” I glanced over at Uncle Bruce who had gone back to looking at stamps. “I know it’s hard to believe, given how I look today, but I was the starting center. Even had the Giants scouting me.”

“I’d forgotten that,” said Uncle Bruce.

“Yeah, that’s a fact, but then the war came and the army, and by the time I got out, it was too late, and so I went to work at Chemical, there in corporate trust. But those were the days, weren’t they Brucie, back at UVM?”

I looked at Arthur, then at Uncle Bruce, and tried to see them when they were half my age then in 1994. Two kids from privileged backgrounds, full of energy, isolated from the troubles of the world, studying to advance themselves or maybe just going along with the advice that Arthur’s father had given them and riding on the arrangements that the older Mr. Kehoe had made for his son, Arthur, and his surrogate son, Uncle Bruce, because they really didn’t have any idea what they really wanted to be when they grew up. But just then, in the prime of things, the war had come and turned their world upside down, turned everyone’s life upside down, and nothing was ever the same, and after the war, the decades past, and here was the starting center, an invalid still living in the home of his parents, more or less alone, unless you counted Maria, and that was a questionable situation, and there at the card table, still wearing his overcoat, was the team manager, sifting through the unorganized sheets of postage stamps belonging to the starting center. The team manager, who had never moved out of his parents’ house.

A kind of sadness mingled with curiosity came over me. How did these two friends feel about the impending demise of one of them, and how was it that these two characters had become such characters?

A few more disjointed exchanges about one thing and another, and Uncle Bruce said he thought we should be going. I wasn’t sure why. Arthur wasn’t going anywhere, and neither were we, that I knew of, except back to 42 Lincoln. I said good-bye to Arthur, and as he expressed his thanks for the visit, Uncle Bruce slipped out of the room ahead of me. I caught up to him on the staircase and followed him out the door.

As we hiked down the sidewalk, neither of us expressed our thoughts. Mine were focused on Arthur, what a character he was, how eccentric, but at the same time, how likable, and you couldn’t think “eccentric” without thinking “Uncle Bruce,” so that’s how my thoughts turned. However, they didn’t go much further before Uncle Bruce brought up quite a different subject and one quite unrelated to anything Arthur or anything we had talked about at Arthur’s: Jenny’s husband, Garrison Keillor.

“Did you know Garrison is famous?” he asked.

“Famous?” I said, a bit puzzled. “Yes, of course I know he’s famous.”

Uncle Bruce disregarded my response. “Everywhere I go, people know who he is. I asked my stockbroker, ‘Do you know Garrison Keillor?’ and sure enough, he’s heard of him. I go into Barnes and Noble and ask, ‘Do you have any books by my nephew Garrison Keillor?’ and they say, ‘Yes, we have a whole row of books by Garrison Keillor.’” Nephew? I thought. It sounded a little odd. “And when I was on the plane to Chicago with Cliff for the Halloween show—they have an entire trade show exhibition just for Halloween costumes—I asked the fellow next to me on the plane, ‘Have you heard of Lake Wobegon, and what do you know but he’s heard of Lake Wobegon and knows all about Garrison.”

I chuckled in amusement over how impressed Uncle Bruce seemed to be by Garrison’s fame, but what came next was frosting on the cupcake. “You know,” he said, “that Garrison is what I’d call eccentric.”[7] True by any conventional measure, I thought, but utterly plain, normal, and boring next to Arthur or Uncle Bruce.

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] I should mention the state of the kitchen at this stage in the history of 42 Lincoln. To accommodate Gaga’s failing eyesight, Uncle Bruce had attached visual aids to things, usually in the form of a big bow tied out of orange yarn. Sometimes signage was added for good measure. For example, to long pull chain to the ceiling light, he had tied a large piece of bright orange cardboard. In and of themselves, the yarn and the cardboard on the pull chain, however unsightly, had a certain amount of logic to them, but what amused me was the large, magic-marker lettering on the cardboard, which read, “LIGHT SWITCH.” As distinguished from the pull chain to what? I wondered. The toaster? There were other notable oddities in the room, as well, such as the postage stamp dispenser taped to a cabinet door. He had cut off the top of an aspirin box, cut a slit in the bottom and inserted a roll of stamps. Above the dispenser, he had taped more signage—”Stamps,” it read, with an arrow pointing down, just for good measure. I noticed too, several thermometers and several clocks, all still in their K-Mart packaging. Just around the corner of the kitchen doorway was the “Presidential Portrait.” Years before, Gaga had hung a cheap, wooden, painted portrait of President Nixon. With each successive president, either she or Uncle Bruce would find a photograph of similar scale and tape it over Nixon’s portrait. Uncle Bruce sat down in Gaga’s special chair, equipped with four equal-sized wheels, in which she could roll within the confines of the kitchen by pushing and pulling gently with her feet on the floor. Over the years, I noticed, Uncle Bruce seemed to have developed a bizarre fetish for using that chair—along with Gaga’s regular wheelchairs. He could never sit still, of course, even in a regular chair, so the wheel chairs gave him a chance to roll back and forth while he talked.

[5] I remember an earlier occasion when I’d accompanied him on a visit to the mansion of some rich, old heiress who had died recently. The mission was to estimate the required truck hauling and warehouse storage capacity of 20 rooms full of furniture and furnishings. Based solely on a simple walk-through, Grandpa figured out exactly what was required in moving van space and storage capacity. He later gave specific instructions to his hired hands, and at the age of 80, even contributed his own considerable muscle to the effort. I watched with fascination as he directed how lamps, chairs, sofas, settees, tables, mirrors, silver, dish ware, pedestals, sculptures, large-framed paintings, bed frames, footboards, headboards, thousands of books, umbrella stands, cartons of all sizes, decorative and utilitarian cabinets of all sorts, and uncountable other objects were to be packed into a compact assemblage so tight there was barely an ounce of air within. In the process, not a thing was scratched or broken.

[6] A gold-digger, of course, as would come clear when Arthur died and his will gave Maria everything—everything except the stamps, which he gave to “Brucie.”

[7] I should note here my reaction to Garrison’s best-seller novel, Wobegon Boy. It contains a passage in which he describes the kitchen of the house of the protagonist’s parents. Every detail came straight out of the kitchen at 42 Lincoln, which Garrison had visited prior to writing the book. Upon encountering the passage, I said to myself, No fair! That material is proprietary to my sisters and me! I chuckled, though, over my observation about our inheritance to the effect that that would make us rich was not our inheritance per se, but the royalties from the best-seller that one of us would write about our family.