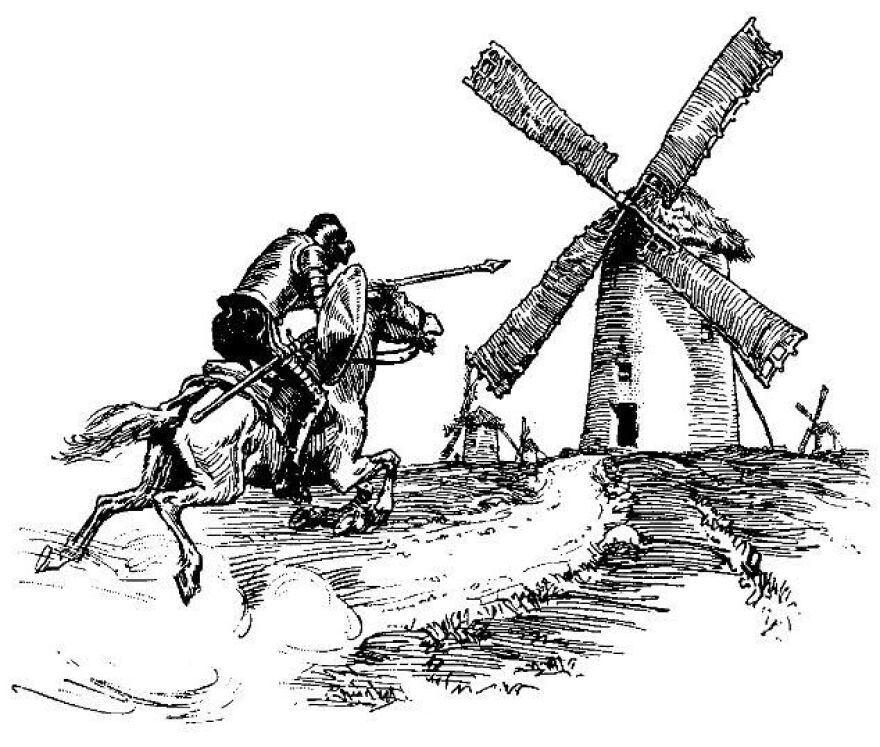

SEPTEMBER 26, 2023 – In October (2011) Beth and I made another trip to New York, this time to check on the recent graduate’s adjustment to the real world . . . of international banking. I used the sojourn as an excuse to venture across the Hudson—this time alone—to tilt again at the family’s windmill.

As usual I walked straight down Highland Cross past 42 Lincoln Avenue to Park Avenue where I’d turn and continue to the Fun Ghoul storefront and Cliff’s office. This time, however, I stopped at the corner to gaze across Park at the cell tower anchored on the tiny parcel adjacent to the borough annex. The east side of the annex, in turn, was across Donaldson Avenue from the Rutherford Borough Hall—once upon a time the school my grandparents had attended.

No one other than Cliff and I knew that the cell tower was a monument to UB and Mother’s mental distortions. In the mid-1990s, AT&T had approached UB about erecting that very cell tower on the roof of the warehouse complex[1]. The rent under the proposed 10-year lease with renewal options would start at $6,000 a month. Since AT&T would cover 100% of the cost of construction, operation and maintenance, the pre-tax annual income would’ve been $72,000; $720,000 over the initial term of the lease—a decent return for not lifting a finger except to sign the lease.

But UB being UB didn’t think to consult with either of the lawyers in the family—Nina or me—or any outside legal or financial expertise. In keeping with the family’s habitual skepticism of experts, UB called . . . Mother. And Mother being Mother didn’t think about anything except where her hyper-anxiety led: potential liability. “What would happen,” she later asked me rhetorically, “if the tower fell down and we got sued?”

I was dumbfounded when she informed me about all this—after the opportunity had come and gone.

“Mother!” I cried out. “When’s the last time you learned of a cell tower falling down, and in any event, haven’t you ever heard of insurance?”

“But what if the insurance company went out of business? Dad says John Gordon’s pension was put at risk because it was invested entirely in Executive Life, a big insurance company in California, which failed. If you read The Wall Street Journal, you’d know all about it.” [2]

“For crying out loud, Mother, I’m not even going to respond to that. What I will point out, however, is that you and Uncle Bruce shot down a chance to make enough money to put all your grandkids through college.”[3]

“They can apply for scholarships,” she said. “Besides, Uncle Bruce said he didn’t want to look out the back door of his house and see a huge ugly cell tower on top of his buildings across the driveway.”

I seethed[4]. I was also disturbed that Mother would refer to 42 Lincoln as “his house” and the warehouses as “his buildings” and scoffed at the suggestion that a cell tower on an already ugly four-story pile of dirty ancient bricks would offend UB’s aesthetic sensibilities—of which he was bereft, save for his choice of ski pants and sporty brand new convertibles back in the day.

As I hesitated at the corner of Park and Highland Cross on that sunny October day in 2011, I recalled my conversation with Mother 16 years before. If the money was as good as gone, the cell tower wasn’t. Instead of craning his neck to see a cell tower on top of the (ugly) warehouse complex as he exited his garbage house, UB could peer at it straight out the window of his second floor “office of the beautiful mind” . . . while he promised Alex another 2,000 pounds within the hour.

“Kiss good-bye the money,” I told myself, “but keep the story.” As I’d often quip to Cliff, the real fortune, after all, wasn’t the inheritance. It was the royalties from the movie we’d make and Cliff would promote. Invariably Cliff would laugh as he uttered the working title, “The World According to Bruce.”

On that day of my silent musing about a lost opportunity, however, Cliff was deadly serious about fulfilling all his upcoming Halloween engagements. He barely had time to greet me before shouting more commands to his frenzied staff.

At 11:30 I approached the back entry of 42 Baghdad Street. My face-off with the vegetation guarding the rear of the house reminded me of Stanley and Livingston lost in the heart of Africa. When I reached the back door I knocked, banged, and shouted but to no effect. I peeked through the louvered blinds on the door and saw in the kitchen a trash heap stretching from wall to wall and about two feet deep. I snapped several photos, the most memorable featuring a can of RAID standing symbolically tall amidst a table top piled with crap.

I then started around the dwelling, aiming for the alternate portal into the heart of darkness—the front entryway. Along the way I stepped up to the tangle of vines covering the west side of the house and hiding the window on the side of what Gaga called the parlor. Parting a section of green growth, I found the opening. The frame, I noticed, was in need of major repair. Also, much of the glazing compound around the panes was missing, exposing a number of the metal triangles that held the glass in place. Blaring inside was a TV or radio. I tapped on the window—lightly at first, then harder, while calling out to UB. No answer.

I decided to cut short the expedition and return to Cliff’s office for ideas, including UB’s cell number. I hadn’t expected Cliff to be on hand still, since in his brief greeting a few minutes earlier he’d told me he was already seriously late for an 11:00 off-site customer appointment. However, he hadn’t yet escaped his frenetic headquarters.

“Sorry, Cliff,” I said, feeling like an ill-timed nuisance. “Uncle Bruce isn’t responding to all my knocking and shouting. What should I do? I need to call him but don’t have his number, and I’m not sure he’d answer anyway.”

“Follow me,” he said, then yelled over his shoulder, “Jimmy! Make sure the ghost costumes are ready to go. I’m leaving for Gasperinis in two minutes!” With me skipping steps to catch up, Cliff race-walked out the back doorway of this office, through the warehouse garage, across the drive and into the jungle. Turning his key to the back door bolt lock he said, “Just tell him that he left the door unlocked.”

I was now on my own at the threshold of insanity.

Upon pushing the sturdy door cautiously inward I felt considerable resistance. It took me a second to realize that the pressure was caused by compression of the garbage lying on the opposite side. I pushed harder; enough to gain entry—and a full view. The place was the most awful I’d ever seen it. Where was the polish lady? I thought.

I waded through the trash in the kitchen and plowed around the corner to the base of the staircase.

“Uncle Bruce!” I called out.

“I hear you!” came his distant reply from upstairs. Proving himself sprightly less than a year from turning 90, he appeared at the landing sooner than I’d expected and began his descent toward me. Clearly he was flustered by my unscheduled appearance: his thin lips were pressed tight and his unsmiling eyes were on the defensive. Moreover, he was missing his “BOO-ret” and separated from his toupee.

“Your back door wasn’t latched,” I said, feigning surprise.

“What are you doing here? I didn’t expect you,” he shouted.

“Didn’t you get my letters? I told you I was coming,” I said, referring to yet another couple of written attempts to jump-start both reconciliation and resolution of “unfinished business.” I’d mentioned that we’d be visiting Byron, Jenny and Garrison over in the city and that “at some point,” I’d make an effort to visit him.

“I got both of them,” he said, “but I wasn’t expecting you this very moment.”

As if he’d flipped a switch, he launched into a sort of apology for the condition of the house, except it wasn’t so much an apology as it was an explanation . . . or rather, excuse . . . for the wholly disgusting mess that filled the place. “I can’t find the help,” he said, and “I don’t have time,” and “I’ve been working on puling things together for taxes.”[5]

These excuses, I reminded myself, were the same that I’d heard from Grandpa 30 years before.

UB led me into the junked-out parlor and continued his babbling as to why things were as they appeared. In time his discourse transformed into a description of his “cash journal,” as he showed me an ancient orange plastic three-ring binder filled with accounting paper covered with notations. It was all rather absurd.

I had to wonder at the odds of his confusing that binder with the identical one I’d discovered five years before in the “viewing room”—the one in which he recorded in two- and three-second increments exactly what was happening in the gay porn he watched on his VCR/TV. I imagined the scene in the movie Cliff and I would some day make, wherein UB’s accountant receives the “porn journal” instead of the “cash journal”—and on rumors spread by the office assistant, gets arrested by the FBI as part of an investigation into a mob-run gay porn tape piracy operation.

Whatever impression UB was attempting to make by showing me the (actual) “cash journal,” it didn’t compensate for the ocean of trash that surrounded us.

“Uncle Bruce,” I said, “what do you say we go out to lunch?”

At first he expressed reluctance, but I persisted, and eventually he came around. He’d always had a good appetite. As we exited the house, I surreptitiously snatched a cassette tape that was spilling out of a garbage bag in the kitchen.[6] I knew full well what the tape contained: phone conversations between UB and the Serbian scoundrel, Alex Nikolic. Following UB down the spongy ramp from the back of the house, I examined the notations on the cassette – “AN – 9/6/11.”

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2023 by Eric Nilsson

[1] “Location, location, location.” Rutherford occupies high ground overlooking the Meadowlands and Manhattan to the east. The highest section is aptly named Ridge Road, lined with somewhat fashionable residences. “Ground Zero,” occupied by the Holman warehouses—the highest structures in the vicinity—was an ideal site for a cell tower.

[2]John Gordon was married to one of Dad’s three California cousins. He was several years into retirement when his pension was jeopardized. Mother was correct about WSJ’s coverage of the ELIC meltdown. What she didn’t know is that I’d been a WSJ subscriber for years. But more pointedly, at the time I was in charge of the bond default division of Norwest Bank’s (later Wells Fargo) Corporate Trust department. Our group administered indenture trusteeships, and one of my own files was the default of a bond issue secured by an insurance product of Executive Life Insurance Company (“ELIC”). When ELIC was declared insolvent (largely a result of having “over-partnered” with the infamous Michael Milken of Drexel Burnham), it was put into receivership under the state insurance commissioner. For years, Norwest and similarly situated indenture trustees fought the commissioner’s priority classification (and payout) of our bondholders’ security. In the end, we prevailed, but not before a “face the music” meeting with hundreds of bondholders in the main ballroom of the Hyatt Grand Central in New York with a remote feed to another large group of bondholders gathered in Dallas. I was drafted by the other trustees and our bevy of lawyers to lead the meeting, starting with a “calm down, take a deep breath” speech. We’d been forewarned of a potentially obstreperous crowd, especially in the course of the high-risk Q and A session following my formal remarks. In case matters got out of control, several of the lawyers were stationed at strategic locations ready to pull the cords to microphones and speakers. Though there were some heated exchanges, they never boiled over.

[3] At 1995 pricing.

[4] And this was all before the Big Fire and all that it revealed; before I’d realized that UB had no intent to administer Gaga and Grandpa’s estates and distribute Mother’s inheritance . . . to Mother, not Alex, who had not yet entered the scene.

[5] As far back as I can remember, not until long past tax season and beyond any normal extension period would my sisters, sons, nieces, and I receive our K-1s from the LLC that owned the warehouse properties.

[6] The irony of UB’s relationship with garbage bags was that most he used for storage.