MARCH 7, 2021 – The details are so intricate and interwoven, only by patient review of the fast-paced, suspenseful, multi-dimensional back-room political dealing can a person appreciate the episode in its full expanse.

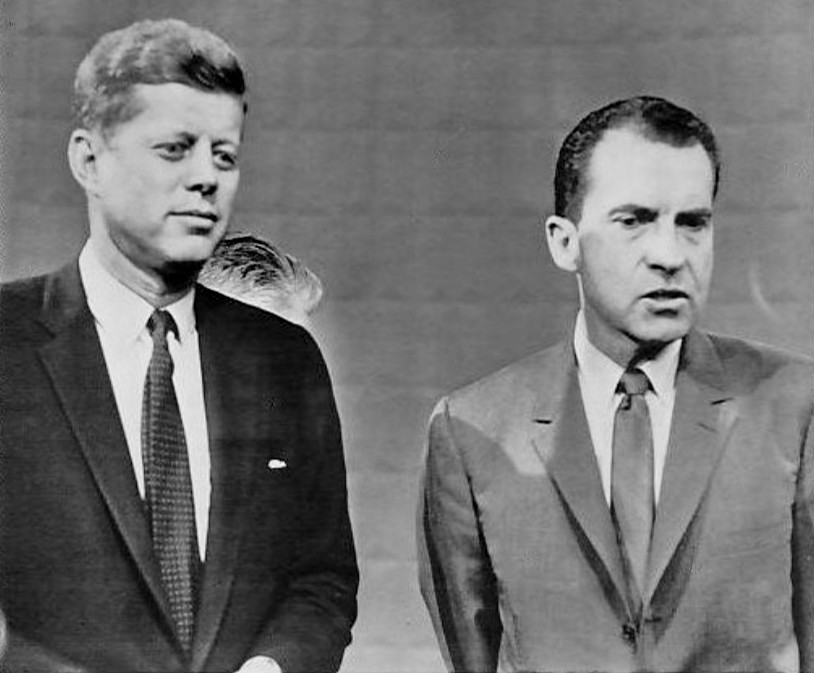

It unfolded in the final days of the 1960 presidential campaign. At the center was Martin Luther King, Jr., adamant about his neutrality, though his father, a leader of the Black Baptist power elite in Atlanta, was a staunch Nixon supporter. Surprisingly by today’s standards, the anticipated Black vote cut 60/40 in favor of Nixon.

Then came the arrest of MLK with Atlanta University students who’d staged a sit-in to protest segregated dining facilities. King had long been dodging the students’ pleas that he join the planned sit-in. He’d wanted the students to wait until after the election. When Kennedy’s campaign negotiated a meeting with King in Miami—King had agreed to meet, not endorse Kennedy—it gave King a convenient excuse to avoid the Atlanta sit-in. When King insisted, however, on giving Nixon an invitation to meet, Kennedy bailed.

With his convenient excuse out the window, King had joined the students. The upshot: jail time, an international media show, and considerable adverse fallout for everyone with a horse in the presidential race. Kennedy especially wasn’t pleased.

As MLK was about to be released, a judge in neighboring DeKalb County issued a bench warrant for King’s arrest for violation of probation on an unrelated charge. The judge sentenced King to four months on a chain gang.

Five months earlier, MLK and Coretta had driven their white friend, writer Lillian Smith, to Emory University Hospital for cancer treatments. A traffic cop stopped them—for integration inside a private vehicle(!) The Kings had moved back to Atlanta from Montgomery a few months before, but MLK hadn’t yet obtained a Georgia license. He was arrested, convicted of a misdemeanor and handed a 12-month suspended jail term.

When King’s family, friends, and supporters appeared at the Atlanta city jail to cheer his release from the sit-in charge, they gasped upon seeing him shackled in irons, pushed into the back seat of a squad car (shared with a German shepherd), and whisked off to a remote state prison, all because of the invalid-license charge.

All hell broke loose before MLK was freed.

Enter three unsung heroes—Sargent Shriver (the Kennedy bro-in-law), and two marginalized campaign members, Harris Wofford and Louis Martin. Clandestinely, they produced the “blue bombshell” (named so because it was printed on blue paper). Except for our heroes, the Kennedy campaign was clueless; all tracks, cleverly erased. The paper handout carried an artfully crafted pitch to Black voters linking Kennedy (mainly Bobby’s phone call to the DeKalb County judge; Jack’s sympathy call to Coretta) to MLK’s early release from prison. On the last Sunday of the campaign, the “bombshell” was distributed miraculously in massive quantities among Black Baptist parishioners.

The Black vote soared to 70/30 in favor of Kennedy. Later analysis revealed that this last minute shift had given Kennedy his narrow victory over Nixon.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2021 by Eric Nilsson