MARCH 18, 2024 – (Cont.) There on the top shelf was a book in mint condition. On its dignified spine was the incongruous title, A Short History of Byzantium: what could be short about a history of an 1,100-year empire?

Were they still among the living, my college history profs would be impressed that I can remember the 1,100-year part; close enough to the precise duration of 1,123 years and 18 days (as it turns out). In a freshman survey course on the history of Western civilization, I’d absorbed and retained enough to know that with Constantine the Great, the Roman Empire was effectively split in two soon after 312 C.E. (the year of his conversion to Christianity)—between Rome back in Italy and what would become Constantinople (now Istanbul) on the shores of the Bosphorus just above the northern part of the Sea of Marmara south of the Black Sea.

To be perfectly honest, of all historical epochs and episodes, Byzantium was not on my list of top-10 favorites or more accurately, “on any kind of list.” The book did not fly off the shelf and into my hands, but I was intrigued by the word “short.” Though published in ancient times (1997), the book anticipated the Age of Short Attention Spans—my own included. Most important, however, was the fact that the tome “owned” the shelf. No other histories of anything were in stock.

The publisher was Arthur A. Knopf, which was familiar to me, but I’d never heard of the author, John Julius Norwich. According to his bio on the inside flap, he was born in 1929 and “educated in Canada, at Eton, at the University of Strasbourg, and at Oxford, where he took a degree in French and Russian.” Upon reading this, I smirked. “educated in Canada”? What on earth . . . er, in Canada . . . did that mean? And “a degree in French and Russian”—was that Russian with a French accent or French with a Russian accent, and in either case, what did that have to do with the history of Byzantium, long or short?[1]

What the author did have going for him was a career in the foreign service, with assignments to Belgrade and Beirut. He’d retired early to write—history—and to his considerable credit, he’d written no fewer than 14 books, including a three-volume history—the long version, apparently—of the Byzantine Empire, from which the book in my hands was a condensation. Under the “Miscellaneous” category of his works on the first page of the book in hand were two titles that suggested a sense of humor: Christmas Crackers, 1970 – 1979 and Christmas Crackers, 1980 – 1989.

The brief Preface and Introduction of A Short History—don’t ask me why the (missing) editor didn’t see fit to combine these—won me over, despite the opening pitch missing the strike zone by a millennium. Despite being an upper crust Englishman (he even served a stint in the House of Lords), he was reassuringly not full of himself.

Surprisingly, the more I read of the Preface/Introduction, the more I could relate to the author, despite his aristocratic background juxtaposed to my own (plebian) past. Rather than tout his educational pedigree, he lamented its deficiencies, particularly in regard to the very subject on which he was about to expound. “[L]et me emphasize,” he wrote, “that this book makes no claim to academic scholarship.”[2] He had the self-confidence to add that any “Byzantinist” was welcome to take potshots at his work. “So be it,” he said.[3]

In fact, Norwich was a refreshing maverick in regard to scholarship, blaming Edward Gibbon, author Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, for having prejudiced generations of scholars into assuming that the rise of the East—Byzantium—was beneath serious examination.

“I’m liking this guy Norwich,” I said to myself. But his next sentence was the clincher:

The four years of ancient Greek that constituted an important part of that public-school [Eton] education that I have already mentioned have not enabled me to read the simplest of Greek texts without a lexicon at my elbow; among primary authorities, I have consequently been obliged to rely almost entirely on those whose works exist in translations or summaries. (Introduction p. xli)

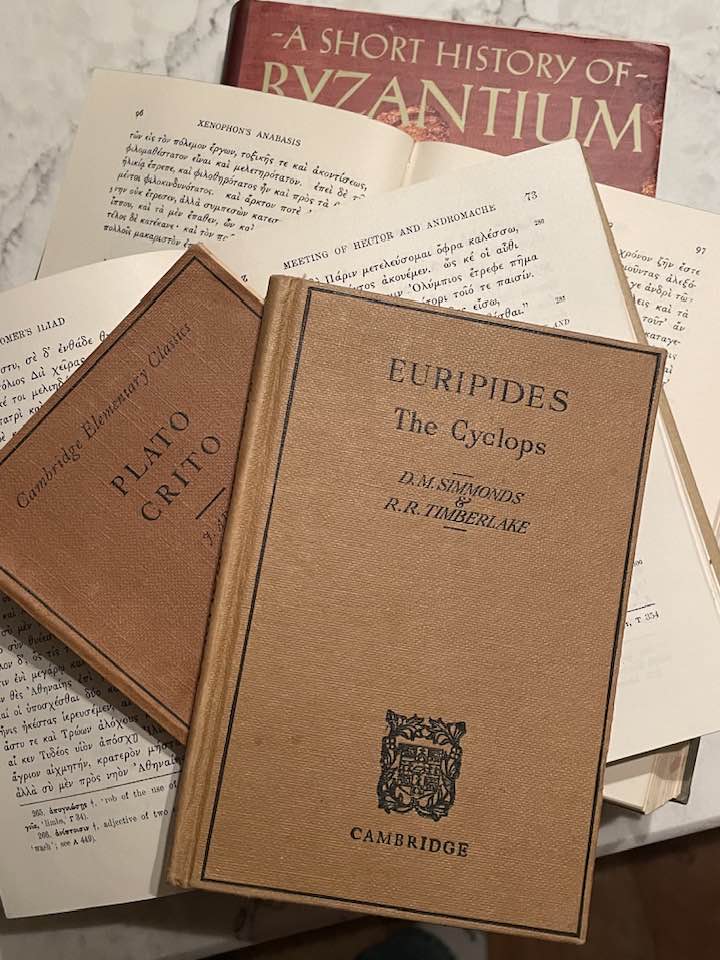

I thought back to my own “four years of ancient Greek,” not at Eton, but at a distinguished New England liberal arts college established in 1794—the same year of Edward Gibbon’s demise at the tender age of 56. The instruction I received was at the level equal to anything that Eton could boast, I’m certain, and the readings were from the heart of the classic literature—Homer’s Iliad, Plato’s Crito, Xenophon’s Anabasis, Euripides’s The Cylops. I turned out top grades all the way through.

But put any of those texts in front of me today, and “without a lexicon at my elbow” I’d be in a world of hurt. It would all be Greek to me. Oops, bad metaphor. (Sorry, Professors Dane and Ambrose (in the case of each, animus eorum in caelis benedicite), not to mention my sorta namesake, Professor Erik Nielsen.)

On the first page of A Short History of Byzantium, my initial instincts about the work and its author were affirmed. With the succinctness more of an investigative journalist than of a PhD candidate stuck in the catacombs, Norwich presented his thesis: Constantine the Great made two decisions that put him on an equal footing of influence with three other historical personages: Jesus, the Buddha, and the Prophet Mohamed. Those decisions were (a) adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire; and (b) moving the capital east—to what became Constantinople. Given the numberless factors—big and small—afoot in the annals of civilization, that thesis struck me as bold. I was compelled to keep reading. I’ve not been disappointed.

I have no intention of giving you a (short) review of The Short History of Byzantium. I’d be quoting such magnificently amazing passages that you (and I!) would find reading the book cover-to-cover a far more efficient undertaking. Nonetheless, I hope to provide one more post (perhaps more) on the perspective that even a superficial overview of Byzantium affords the startled observer of today’s crazy world.

Then, by popular demand, believe it or not, I might supplement War Stories with a few more . . . war stories.

Hang onto your hat a little longer. (Cont.)

Subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

© 2024 by Eric Nilsson

[1] I’m surprised that a book published by Knopf wasn’t better edited. The very first sentence of the Preface contained a glaring misprint, ironically in the course of projecting exactitude, casting the end-date of the Byzantine Empire as “Tuesday, 29 May 2453.” If I’d retained anything from that survey course back at Bowdoin (apart from the division of the Roman Empire into West and East), it was that the Ottomans brought down Byzantium in 1453. But more to the point, I knew by kindergarten—okay, okay, let’s say second grade—that the year 2453 was in the distant future.

[2] (Introduction, p. xli – but only by inference from the number on the preceding page of the intro; the (absent-minded) editor omitted the number on the page from which I quote.)

[3]I’m reminded of another riveting history by a “non-scholar”: Bitter Glory: The History of a Free Poland from1918 – 1939 by Richard Martin Watt. A graduate of Dartmouth College, Mr. Watt spent much of his vocational life as an executive—eventually president and board chair—of a large New Jersey-based construction company. On the side he’d developed an abiding avocational interest in European history, however, and wrote two other books besides Bitter Glory. I’d encountered the book during my own Polish-centric dive into European history. Of the dozen or so Polish history books I’d consumed—including the seminal work on the subject, a two-volume work by British scholar Norman Davies, God’s Playground: A History of Poland from Origins to 1795 (Vol. I) and from 1795 to the Present (Vol. II)—Mr. Watt’s history was one of the best I’d encountered in Polish-related historiography.