NOVEMBER 24, 2021 – I admit that writing a book review after reading a single chapter is as premature as reviewing a five-course meal after the appetizer. However, sometimes the writing—or dining—is so extraordinary, the reviewer feels equipped to express early admiration.

The book, in this case, is Lincoln Highway by Amor Towles. Several years ago I’d devoured another acclaimed work of his, A Gentleman in Moscow, and thoroughly enjoyed it. One chapter into his latest work, and I’m “all in”

Towles is an artist in his writing style as well as in plot design and character development. His insight into the human condition is also virtuosic. Like a master chef whose every dish reflects originality, he cooks to perfection, then presents his work in the form of fine art. As a dining guest, you feel edified, partaking in sustenance that fortifies you for making the world a better place—simply by your surprisingly reflexive appreciation for extraordinary writing.

So far, I’ve ridden with Emmett Watson—the protagonist—and the kindly Warden of a detention center in Salinas, Kansas to young Emmett’s family farm near Morgen, three hours west. Emmett’s father, I’ve learned, was a well-educated Easterner who eschewed his family’s old wealth to make something of himself from the ground up—a million miles away. The father failed at farming, however, and wound up penniless, hopeless, and heartsick, dying long before his time. His premature death is what led to Emmett’s early release from an 18-month sentence for manslaughter, apparently; details to follow—presumably.

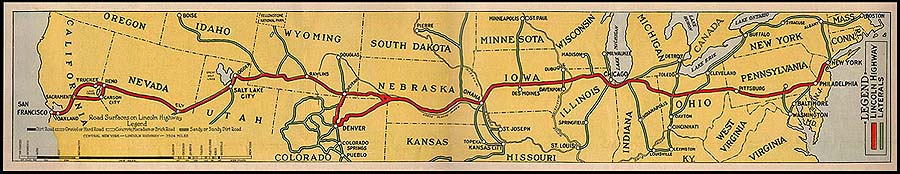

In the first chapter, “Ten” (of 10, numbered in reverse chronological order), the reader learns that Emmett is close to Billy, his precocious, much younger brother, who’d been under the care of charitable neighbors during Emmett’s detention. The two are now plotting their getaway from a place of bad luck, when out of nowhere appear Emmett’s two detention friends, “Woolly” and “Duchess.” They’d hidden themselves in the trunk of the Warden’s car. Just before the escapees surfaced, Billy had been lobbying Emmett to travel west—on the transcontinental Lincoln Highway—to San Francisco, where their runaway mother had sent the last of nine postcards home. Woolly and Duchess lean on Emmett (and Billy) to drive east to Woolly’s family “camp” in the Adirondacks to recover $150,000 cash (1946 dollars) hidden in the walls. Emmett will have none of it, despite being offered a third of the take.

Towles presents an intricate tale, feeding the reader details sparingly and delicately. Every morsel savored whets the appetite for more. For added flavor, Towles alters the point of view of narration, moving the reader from one side of the table to another.

A virtuoso writer like Towles knows precisely how to cultivate details and serve them in a blend that influences the reader’s outlook on life. This process occurs visually, aurally, emotionally, and cogitatively; it applies to setting, characters, and plot development—tension and resolution.

Only midway into the appetizer, I heartily recommend Towles’s literary feast, Lincoln Highway.

(Remember to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.)

© 2021 by Eric Nilsson